What's past is prologue - British prime ministers come and go, a revolving door

The United Kingdom is often referred to as America's mother country. The historic relationship between the U.K. and its former colonies, severed by the 18th century Revolutionary War, has evolved over time into a close 21st-century bond. The current leaders of arguably the world's two most prominent democracies reaffirmed the "special relationship" between the U.S. ...

The United Kingdom is often referred to as America's mother country.

The historic relationship between the U.K. and its former colonies, severed by the 18th century Revolutionary War, has evolved over time into a close 21st-century bond.

The current leaders of arguably the world's two most prominent democracies reaffirmed the "special relationship" between the U.S. and U.K. in a phone call Tuesday, Oct. 25, between President Joe Biden and new Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, the first non-white British leader in the European nation's long history.

Frank Nickell has traveled to England on multiple occasions, most recently in 2019, and the longtime Southeast Missouri historian agreed to participate in a brief Q&A session to highlight some of the differences between our two nations.

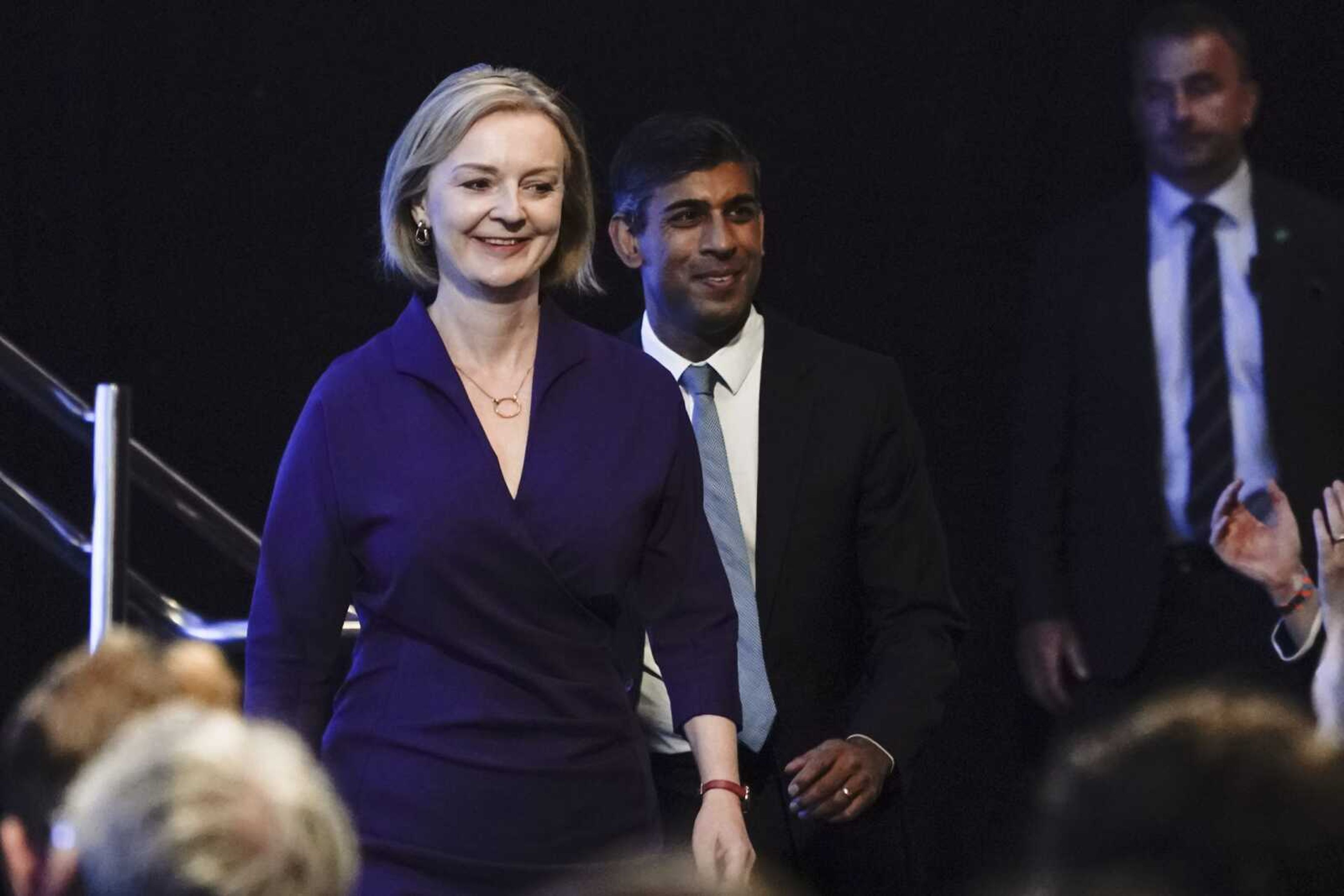

Sunak's accession to the U.K.'s top job follows the 50-day premiership of his predecessor, Liz Truss -- the shortest by far in the U.K.'s long history. Sunak has become the third head of government in this calendar year -- following Truss and Boris Johnson. It seems British leaders come and go at a markedly faster rate than in our country. Why so different?

There is no written Constitution in the U.K., unlike in our country, where national leaders pledge fealty to the U.S. Constitution. We Americans want everything written down, a set body of laws, a "rule of law," if you will, but the British chose a more flexible, more casual system. Therefore, there is no objective standard of practice for government in Great Britain. Prime ministers, then, are dictators in a sense while they hold office. The U.S. standard is an eight-year maximum, or more exactly, two elected four-year terms, for presidents; that's in our Constitution. But in the U.K., if a leader can keep the support of enough of the ruling party in Parliament, he or she can serve for longer periods. Labour's Tony Blair was British prime minister for 10 years; Margaret Thatcher of the Conservative Party served 11. William Pitt, called "The Younger," served a total of 20 years combined in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Our longest-serving leader, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was U.S. president for a dozen years from 1933 to 1945. The 22nd Amendment was passed after FDR's death preventing that length of service ever again. By contrast, prime ministers can serve a very long time or very briefly since there is no fixed term as there is for U.S. presidents.

The U.S. came out of Great Britain and the U.K. system was the government we knew and understood at the time. Yet the American Framers chose not to recreate the British idea of a parliament when our republic was founded. Why?

It's important to recall the U.S. and U.K. basically had a poor relationship until 1939, when King George VI came to America seeking U.S. support in the Second World War. WWII changed the U.S.-U.K. relationship profoundly. Back in the late 1700s, the Framers reacted negatively to some of what they saw as the worst in the British system. Taxation without representation, for example. There was no appetite for an American king either -- even a ceremonial one, as is the case today in the U.K. The British system also didn't have the checks and balances inherent in our system -- e.g., co-equal branches of federal government: executive, legislative, judicial. Even today, the Brits don't have our long-cherished notion of the separation of powers.

Every week when Parliament is in session, the prime minister -- the head of government -- must appear for a question session in the House of Commons. We have nothing like that in the U.S. There is no mandatory appearance for our presidents before Congress. Even a press conference is entirely at the president's discretion. Does it seem then, that prime ministers are held to account in a way U.S. presidents are not?

Perhaps. Keep in mind that "Prime Minister's Question Time" is usually a rough-and-tumble, no-holds-barred session. The British have a monarch, now King Charles III, the head of state, who occupies a dignified position. In the U.S., we have no corollary. Americans see the president as head of state and head of government, and we don't like to see our commander-in-chief "roughed up" in public. If Congress talked in-person to Joe Biden or to Donald Trump or any president you can name the way the British speak to their prime ministers, we simply wouldn't stand for it. We want our presidents treated with some dignity. In fact, if President Biden was ever verbally assaulted publicly the way the British parliamentary members speak routinely to their prime ministers, I daresay even many Republicans would leap to (Biden's) defense. We just have a different understanding of government on our shores.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.