U.S. suspects cellphone spying devices in DC

For the first time, the U.S. government has publicly acknowledged the existence in Washington of what appear to be rogue devices foreign spies and criminals could be using to track individual cellphones and intercept calls and messages. The use of what are known as cellphone-site simulators by foreign powers has long been a concern, but American intelligence and law enforcement agencies, which use such eavesdropping equipment themselves, have been silent on the issue until now...

For the first time, the U.S. government has publicly acknowledged the existence in Washington of what appear to be rogue devices foreign spies and criminals could be using to track individual cellphones and intercept calls and messages.

The use of what are known as cellphone-site simulators by foreign powers has long been a concern, but American intelligence and law enforcement agencies, which use such eavesdropping equipment themselves, have been silent on the issue until now.

In a March 26 letter to Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden, the Department of Homeland Security acknowledged last year it identified suspected unauthorized cell-site simulators in the nation's capital. The agency said it had not determined the type of devices in use or who might have been operating them. Nor did it say how many it detected or where.

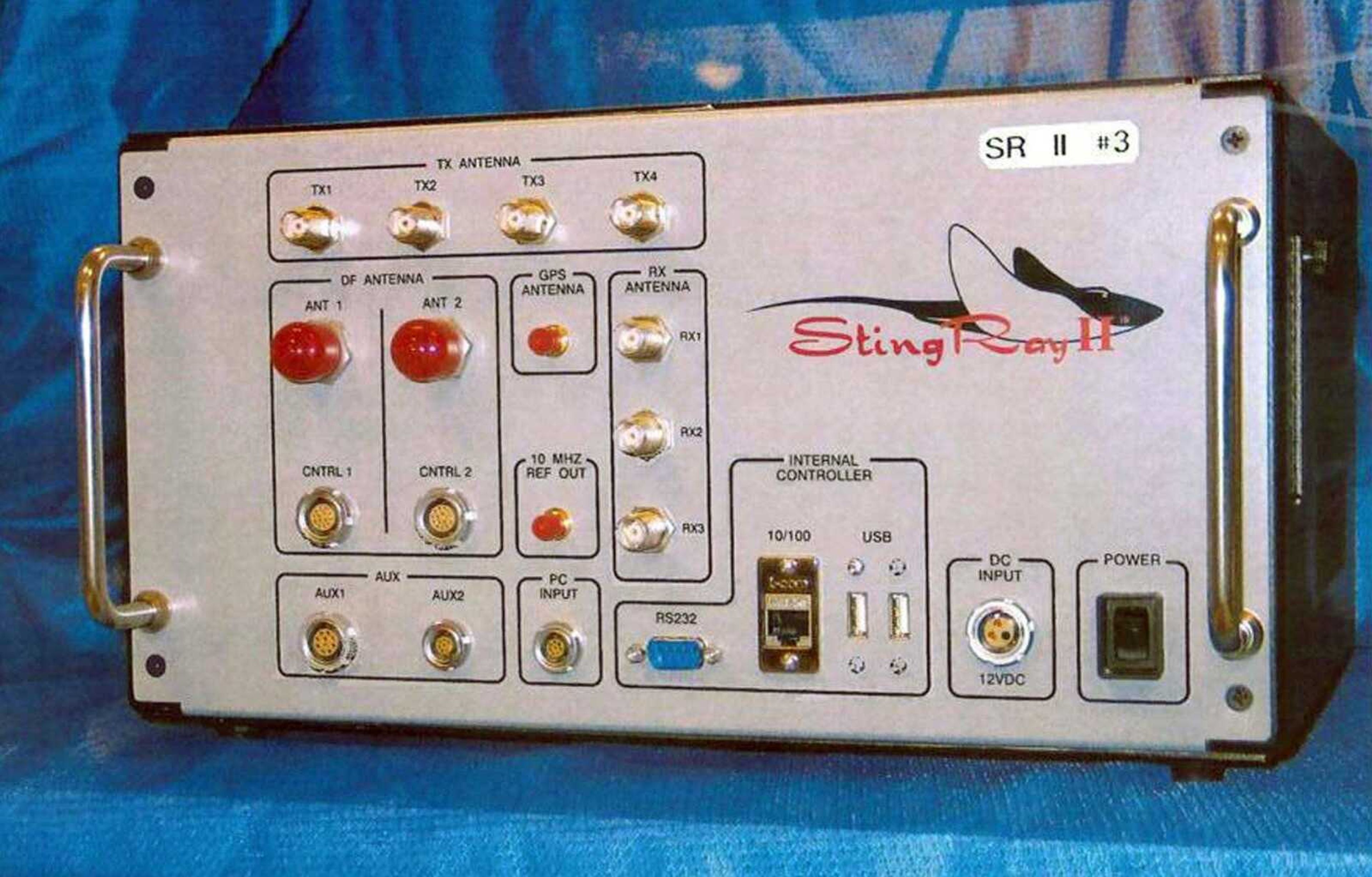

The agency's response, obtained by The Associated Press from Wyden's office, suggests little has been done about such equipment, known popularly as Stingrays after a brand common among U.S. police departments. The Federal Communications Commission, which regulates the nation's airwaves, formed a task force on the subject four years ago, but it never produced a report and no longer meets regularly.

The devices work by tricking mobile devices into locking onto them instead of legitimate cell towers, revealing the exact location of a particular cellphone. More sophisticated versions can eavesdrop on calls by forcing phones to step down to older, unencrypted 2G wireless technology. Some attempt to plant malware.

They can cost anywhere from $1,000 to about $200,000. They are commonly the size of a briefcase; some are as small as a cellphone. They can be placed in a car next to a government building. The most powerful can be deployed in low-flying aircraft.

Thousands of members of the military, the NSA, the CIA, the FBI and the rest of the national-security apparatus live and work in the Washington area. The surveillance-savvy among them encrypt their phone and data communications and employ electronic countermeasures. But unsuspecting citizens could fall prey.

Wyden, a Democrat, wrote DHS in November requesting information about unauthorized use of the cell-site simulators.

The reply from DHS official Christopher Krebs noted DHS had observed "anomalous activity" consistent with Stingrays in the Washington area. A DHS official who spoke on condition of anonymity because the letter has not been publicly released added the devices were detected in a 90-day trial beginning in January 2017 with equipment from a Las Vegas-based DHS contractor, ESD America.

Krebs, the top official in the department's National Protection and Programs Directorate, noted in the letter DHS lacks the equipment and funding to detect Stingrays even though their use by foreign governments "may threaten U.S. national and economic security." The department did report its findings to "federal partners" Krebs did not name. That presumably includes the FBI.

The CEO of ESD America, Les Goldsmith, said his company has a relationship with DHS but would not comment further.

Legislators have been raising alarms about the use of Stingrays in the capital since at least 2014, when Goldsmith and other security-company researchers conducted public sweeps locating suspected unauthorized devices near the White House, the Supreme Court, the Commerce Department and the Pentagon, among other locations.

The executive branch, however, has shied away from even discussing the subject.

Aaron Turner, president of the mobile security consultancy Integricell, was among the experts who conducted the 2014 sweeps, in part to try to drum up business. Little has changed since, he said.

Like other major world capitals, he said, Washington is awash in unauthorized interception devices. Foreign embassies have free rein because they are on sovereign soil.

Every embassy "worth their salt" has a cell tower simulator installed, Turner said. They use them "to track interesting people that come toward their embassies." The Russians' equipment is so powerful it can track targets a mile away, he said.

Shutting down rogue Stingrays is an expensive proposition requiring wireless network upgrades the industry has been loath to pay for, security experts say. It could also lead to conflict with U.S. intelligence and law enforcement.

In addition to federal agencies, police departments use them in at least 25 states and the District of Columbia, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

Wyden said in a statement Tuesday "leaving security to the phone companies has proven to be disastrous." He added the FCC has refused to hold the industry accountable "despite repeated warnings and clear evidence that our phone networks are being exploited by foreign governments and hackers."

After the 2014 news reports about Stingrays in Washington, Rep. Alan Grayson, D-Fla, wrote the FCC in alarm. In a reply, then-FCC chairman Tom Wheeler said the agency had created a task force to combat illicit and unauthorized use of the devices. In the letter, the FCC did not say it had identified such use itself, but cited media reports of the security sweeps.

That task force appears to have accomplished little. A former adviser to Wheeler, Gigi Sohn, said there was no political will to tackle the issue against opposition from the intelligence community and local police forces that were using the devices "willy-nilly."

"To the extent that there is a major problem here, it's largely due to the FCC not doing its job," said Laura Moy of the Center on Privacy and Technology at Georgetown University. The agency, she said, should be requiring wireless carriers to protect their networks from such security threats and "ensuring that anyone transmitting over licensed spectrum actually has a license to do it."

FCC spokesman Neil Grace, however, said the agency's only role is "certifying" such devices to ensure they don't interfere with other wireless communications, much the way it does with phones and Wi-Fi routers.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.