Special report: Cape Girardeau PD has high rate of "unfounded" rape cases

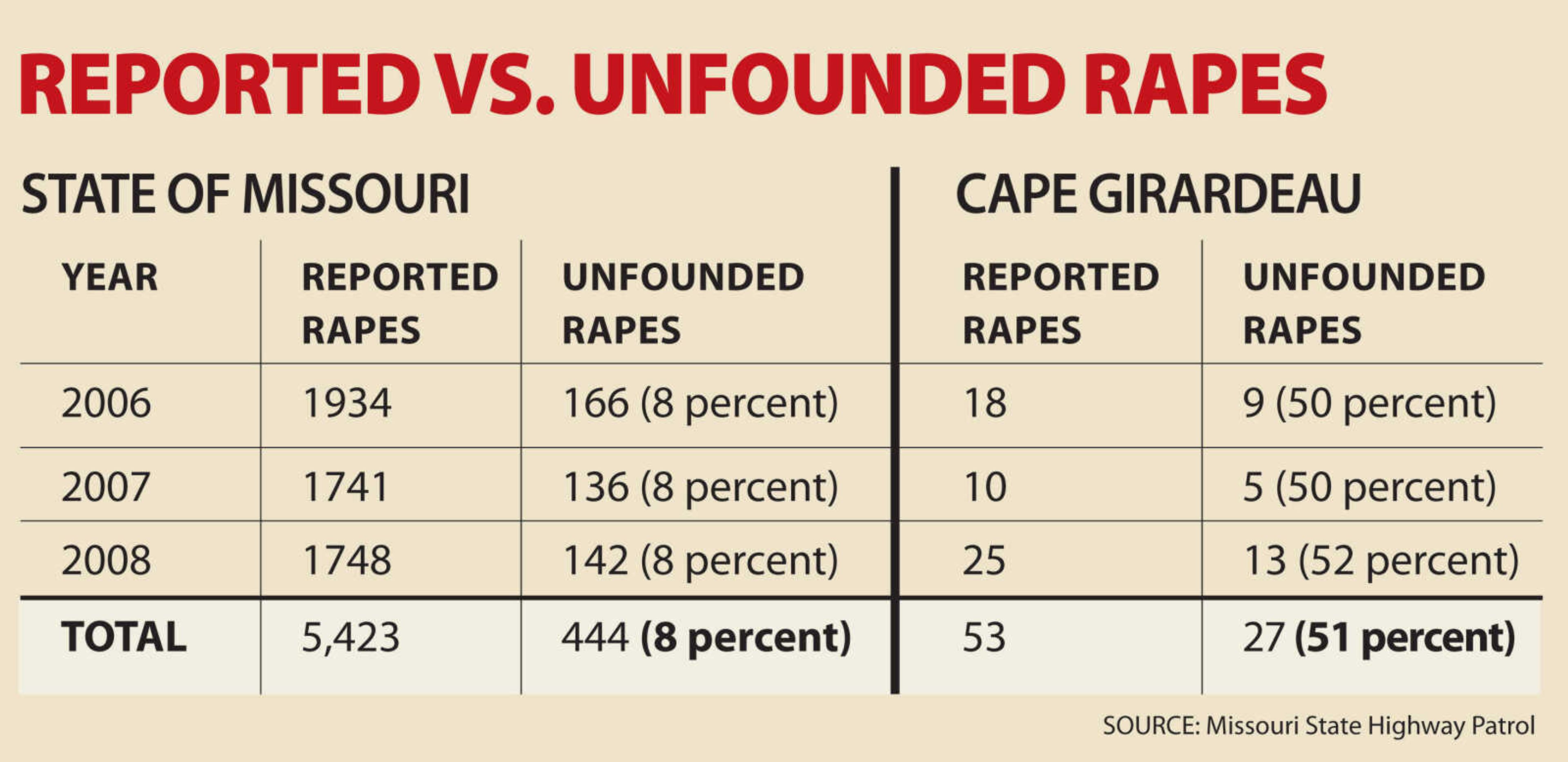

Fifty-three women have reported rapes in the last three years to Cape Girardeau police. Police investigators determined that just over half of those rapes were "unfounded" or that they never occurred. That number is six times higher than what is reported across the state, according to the highway patrol...

Fifty-three women have reported rapes in the last three years to Cape Girardeau police.

Police investigators determined that just over half of those rapes were "unfounded" or that they never occurred. That number is six times higher than what is reported across the state, according to the highway patrol.

Rape is one of the most difficult crimes to investigate. The evidence often boils down to one person's word against another's, making rapes difficult to prove in court.

But when should reports of rapes be classified as "unfounded"? It's a question disputed nationwide, much of it boiling down to how individual departments record their unfounded rapes. Should a recanted statement prove that a rape didn't exist, even if the alleged victim may be scared or have been pressured by outside forces to let the case drop? What about cases where alleged victims had lied about certain portions of their statement? The determination of rape reports as unfounded appears to be mired in confusion and miscommunication that can lead to inaccurate reporting of crimes. National statistics vary wildly on how many rape cases are discarded.

A 10-month Southeast Missourian investigation into unfounded rape claims throughout Southeast Missouri even surprised Cape Girardeau Police Department officials, who, alarmed at the high percentage of unfounded rapes, have since started new policies in rape cases. After repeated inquiries to the Missouri State Highway Patrol about its own unfounded rape statistics, a director of the Uniform Crime Reporting Program for the patrol suggested that the topic, previously off the radar, may be an issue highlighted at future training sessions.

So many discrepancies abound about the prevalence of false rape complaints that a 2006 Cambridge Law Journal article on the topic estimates that rates of unfounded cases range from 1.5 to 90 percent.

"This isn't something we only see in rural communities -- it's a problem in metropolitan areas, too," said Joanne Archambault, executive director of End Violence Against Women International.

The numbers

According to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, a nationwide organization founded by the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape, of the less than 10 percent of rape victims who report their assaults to police, only 3 to 8 percent of those turn out to be unfounded reports, based on a culmination of studies from other entities.

In 2008, about 8 percent of the forcible rapes reported to law enforcement agencies in Missouri were later cleared as "unfounded," according to Laurie Crawford, director of the Uniform Crime Reporting Program for the Missouri State Highway Patrol. That means that following an investigation, the crime is either found to not have occurred or to not have occurred in a manner that would legally constitute forcible rape, said Bill Welch, an auditor for highway patrol's records division.

"It's one of those things that you know when you see it," Welch said.

Cape Girardeau police chief Carl Kinnison, who says officers write up the cases "at face value," acknowledged the high numbers were surprising and suggested several possible explanations.

Following a recent UCR audit of its 25 rape cases reported in 2008, the department enacted a new policy: It will begin keeping cases open unless strong evidence supports the victim's recantation, Kinnison said.

"In the past, we were believing the victim if she says 'I lied,'" Kinnison said.

For 2008, however, the policy change did not affect the 13 unfounded cases among the 25 total reported for that year, Kinnison said, though it would have lowered the percentage for previous years.

Some departments may be taking reports of sexual assaults as other things, such as requests for service, and not reporting them as rape, accounting for a lower number of reported rapes that will then actually be turned over to detectives for investigation, Kinnison said.

Another factor that could contribute to 50 percent of Cape Girardeau's reported rapes being unfounded involves the thoroughness of the investigation, Kinnison said.

"The more efficient the department, the more unfoundeds you will see," he said.

Kinnison cited a widely publicized 1994 study by Purdue University sociology professor Dr. Eugene J. Kanin that determined 41 percent of forcible rape cases reported to a metropolitan Midwestern police department turned out to be false allegations.

Kanin argued that the more thorough investigations a department conducted, the greater chance they would have a higher number of unfounded cases.

A report recently issued by the American Prosecutors Research Institute, co-authored by Archambault, director of End Violence Against Women, harshly criticized Kanin's study because his conclusions were based on the findings of false allegations by the detectives of one department, Archambault said.

Kanin's study was not representative of the "real world" because the investigators in the study put pressure on the victims to recant their stories, said Wendy J. Murphy, a former prosecutor who specialized in rape cases and a professor at New England School of Law.

"Women were pressured to recant -- cops don't do that," Murphy said.

Murphy said in her 20-plus-year career, she'd never seen a false rape claim.

"It's not scientific, but it's not nothing," she said.

Scott County investigator Capt. Gregg Ourth said he hasn't seen many unfounded rape cases, and the few he has seen involved victims who may have suffered from mental illness.

The rural county reported no unfounded rapes of its six turned over to the highway patrol's records division over the past three years.

The Jackson Police Department reported that three of its seven reported rapes were unfounded following further investigation, and three of the Sikeston Department of Public Safety's 32 rape cases for the years 2006 through 2008 were unfounded, according to the state data.

"In my opinion, nothing is unfounded -- there's always something you can do with it," said Bollinger County investigator Stash Petton.

Petton said he'll take the investigation "as far as humanly possible." He cited one case where he knew a victim had reported several previous rapes that turned out to be false; the fourth time she reported a rape, the suspect she named confessed to deputies and was arrested.

According to the Uniform Crime Reports, designed to create a standard measure for crime data, in Jefferson City, Mo., with a population of 885 fewer people than Cape Girardeau, 60 forcible rapes were reported over the past three years and 8 percent of those were deemed unfounded.

Police departments in larger Missouri cities like Springfield and St. Louis reflected much lower numbers of unfounded rape cases than Cape Girardeau.

Over the past three years, about 7 percent of the 267 rapes reported to Springfield police were unfounded, according to the state statistics.

Of the 871 rape complaints taken by St. Louis metropolitan police department, 5 percent were cleared in the unfounded column.

Welch cautioned against comparing UCR data from one jurisdiction to another because of differences in demographics.

"Trying to compare them may not be accurate even if they are relatively the same size," Welch said.

Though the purpose of the UCR program at its inception in 1929 was to create a reliable standard of measurement for crime statistics across the nation, the system may be too general to provide a realistic portrayal of something as complex and misunderstood as unfounded rape allegations.

"You're taking one statute here in Missouri and squeezing it into one definition when there may be a whole different statute in Texas," said Welch, the highway patrol auditor.

Part of the inconsistency may stem from a lack of understanding about how certain rape reports should be categorized, Welch said.

In cases where the victim recants during the investigation, saying she made up the rape, Cape Girardeau police typically cleared those cases, considering them unfounded.

In Kanin's study, victim recantation was used as the sole reason for marking a rape allegation as false, something Archambault said she strongly advises investigators against doing. Many genuine victims of rape will at some point take back their allegations because of the social and emotional consequences of reporting the rape, Archambault said.

"Imagine the power we give a rapist when the victim recants and is not believed," Archambault said.

Murphy, the former prosecutor, said the use of the word "unfounded" serves to support common mythologies surrounding the crime of rape and that a different measuring system should be established.

"It's a harsh, powerful, incorrect word," Murphy said. "It gives scientific support to the myth that women lie about rape."

Welch said UCR standards dictate that investigators should proceed with their investigation regardless of whether the victim takes back her original story.

"They should not be deterred by what the victim says. They have to follow through with the investigation and verify the veracity of what the victim is saying," Welch said.

At the Springfield Police Department, investigators must prove the rape did not happen in order to consider it an unfounded crime -- something that "just does not happen that often," said Sherry Royal, custodian of records for the department.

"It's traumatic -- I could see someone saying it didn't happen just so they don't have to go through with it," Royal said.

The investigations

In December 2007, a waitress in her late teens was at a party with a friend. She left to go to a Cape Girardeau bar and returned to the house of a man she knew. There, they smoked cigarettes, listened to music and eventually had sex, an act the woman described as not consensual. She became angry afterward and told police she had called several friends to come get her from the man's house. Six days after reporting the rape, she told a Cape Girardeau sex crimes investigator that she had used poor judgment, was not raped and did not want the report to go any further.

The case is an example of one where Cape Girardeau police might now choose to keep the file active, but previously it had been classified as unfounded, the case cleared from the yearly totals of actual rapes.

"I'm always so cautious myself to say these things are unfounded because it doesn't cost anything to keep it open," Archambault said.

Because police traditionally measure their success in terms of their "clearance rates," or how few active cases they have at the end of the year, a strong temptation exists for some departments to clear rape cases too quickly, Archambault said.

"Historically, they've been pressured to close them because of clearance rates," she said.

Because of the serious cost to the victim when a legitimate rape case is discounted, the classification shouldn't be used as a clearing mechanism, Archambault said.

Kinnison said these cases represent a difficult decision for the department because the department wants to respect the victim but the department doesn't want to be penalized for having too many open cases when there is likely no way to resolve it without the victim's cooperation. The success of the department can be judged by the community based on the number of cases that are cleared and the number of cases that are left open, he said.

Doug Richards, director of Southeast Missouri State University Department of Public Safety, said he doesn't allow his detectives to classify cases as unfounded. If there is a suspect named in the case, it is turned over to the Cape Girardeau County prosecuting attorney's office for consideration.

"I don't want there to be any questions that we aren't taking these cases seriously," Richards said.

Of the five rape and two sexual misconduct cases reported to campus police over the past three years, two remain active investigations and five were turned over to prosecutors, who declined to file charges in all of them.

Turning every case over to prosecutors isn't necessarily the most efficient way to handle rape cases because investigators should be able to "sell" the case, Archambault said.

"If we send a case to a prosector, we should believe we have a case," Archambault said.

According to rape reports requested by the Southeast Missourian, in the fall of 2008, a 21-year-old woman reported that she had been raped at a fraternity house. She became upset when investigators questioned her about her drinking activities. At a club earlier that night, a witness saw the victim talking to, flirting with and hanging on the suspect. "I know how she is," that witness told police. The victim stopped returning investigators' phone calls, and prosecutors advised police they would not file charges based on the belief the rape allegation was made up. The case was classified as unfounded.

"For a woman truly victimized in a sexual assault, it's a very challenging thought to see this thing through to the very end," said Lt. Mark Ballser of the Liberty Police Department.

Cape Girardeau investigator Debi Oliver said she begins every case by assuming the victim is being absolutely truthful.

Upon request from the Southeast Missourian, Archambault reviewed a handful of investigative reports of closed, unfounded rape cases obtained by Missouri Sunshine Law requests.

"I thought they were doing a pretty good job by going through with the investigations," Archambault said.

However, Archambault said she did see some red flags in some of the reports by Cape Girardeau officers that indicated a pattern of judgments being passed. It's a trap she said was easy for investigators to fall into because of what she called "our own institutional bias" and lack of training and education.

"These cases just get so messy," Archambault said.

Concerned that genuine rape victims could be having their cases classified as unfounded, Archambault suggested assembling multidisciplinary teams to review some of the unfounded cases.

In one report, Archambault said, the victim kept repeating the incident had been her fault because she'd been intoxicated, a common occurrence with rape victims, but not necessarily one that fits the stereotype most people have of a rape, she said.

"I find that a big indicator that she's being truthful," Archambault said.

These types of victims are some of the most high-risk, she said.

"There is still a great skepticism among traditional investigative entities that women lie about being assaulted, and the lies are for pretty traditional reasons -- they want to get someone in trouble, or they regret sexual activity they participated in," said Tammy Gwaltney, director of Southeast Missouri Network Against Sexual Violence.

"We do see some revenge reporting, if someone has a grudge," Ballser said.

In another Cape Girardeau rape report, Archambault said the victim admitted using crack cocaine and that if a victim were lying and got to "make her own script," she wouldn't likely incriminate herself in a felony.

Kinnison said investigations are "evidence-based," citing an example where a victim's story was contradicted by a surveillance camera showing she accompanied the suspect willingly to take money from her ATM account.

When a case is unfounded, the evidence is preserved and the case can always be reopened in light of new evidence, Oliver said.

"We have that option, and we sincerely mean it," she said.

Oliver, who holds a master's degree in psychological counseling, will receive free training from Archambault next month on a merit-based scholarship. In addition to being executive director of End Violence Against Women International, Archambault is also the president and training director of Sexual Assault Training and Investigations, which provides training and expert consultation to law enforcement regarding crimes of rapes and sexual assault.

Welch said after completing his UCR audit of the 2008 rapes cases reported in Cape Girardeau, he found the investigations to be accurate, aside from the previously mentioned change in classification.

"The biggest thing agencies need to do is to just let the numbers fall where they may," he said, adding that crime sometimes fluctuates without explanation.

"This has been a good exercise for us," Kinnison said of examining the unfounded rapes.

"The thing I'm most concerned about is that we're doing it right," he said.

Former Southeast Missourian intern Brian Schraum contributed to this report.

bdicosmo@semissourian.com

388-3635

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.