Social media helps drive historic Cuban exodus to U.S.

PENAS BLANCAS, Costa Rica -- As summer began to bake the central Cuban city of Sancti Spiritus, Elio Alvarez and Lideisy Hernandez sold their tiny apartment and everything in it for $5,000 and joined the largest migration from their homeland in decades...

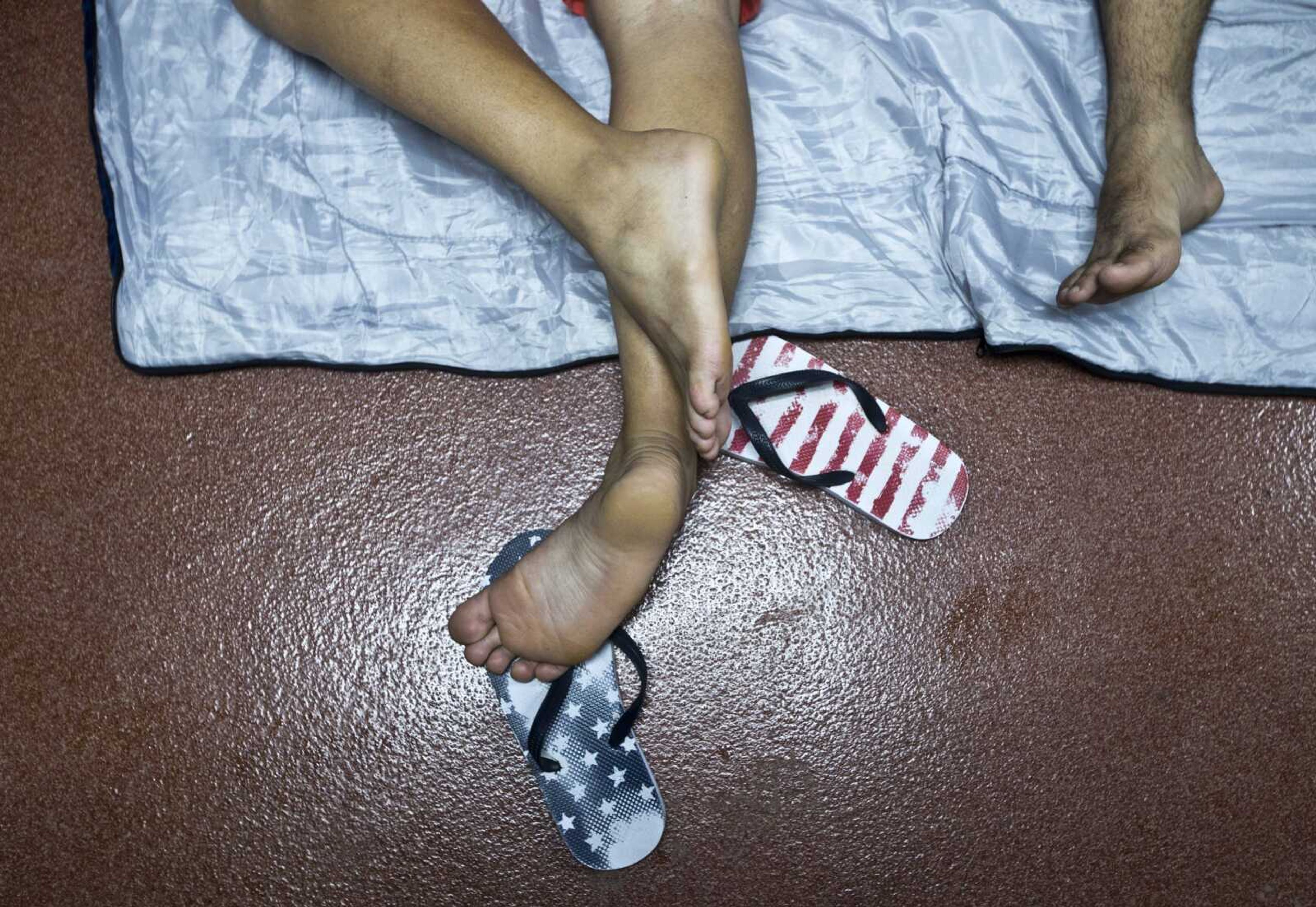

PENAS BLANCAS, Costa Rica -- As summer began to bake the central Cuban city of Sancti Spiritus, Elio Alvarez and Lideisy Hernandez sold their tiny apartment and everything in it for $5,000 and joined the largest migration from their homeland in decades.

Buying two smartphones for $160 apiece on a layover on their way to Ecuador, they plugged themselves into a highly organized, well-funded and increasingly successful homebrewed effort to make human traffickers obsolete by using smartphones and messaging apps on much of the 3,400-mile overland journey that's become Cubans' main route to the U.S.

Some 45,000 Cubans are expected to move by bus, boat, taxi and on foot from Ecuador and other South and Central American countries to the Texas and California borders this year, afraid the normalization of relations between the U.S. and Cuba will mean an imminent end to special immigration privileges that date to the opening of the Cold War.

With thousands more taking rafts across the Florida Straits, 2015 may witness the biggest outflow of Cubans since the 1980 Mariel boatlift that hauled 125,000 people across the Florida Straits.

The overland exodus has caused a border crisis in Central America, set off tensions in the newly friendly U.S.-Cuban relationship and sparked rising calls in the U.S. to end Cubans' automatic right to legal residency once they touch U.S. soil.

At the heart of it all is Cubans' ability to cross some of the world's most dangerous territory relatively unscathed by the corrupt border guards, criminal gangs and human traffickers known as coyotes who make life hell for so many other Latin American migrants.

Key to that ability is the constant flow of information between migrants starting the journey and those who have just completed it.

"Those who've arrived have gotten in touch with their acquaintances, their friends, and tell them how the route is. That means that no one needs a coyote," said Hernandez, a 32-year-old psychologist. "You go making friends along the way. I myself have 70, 80-something friends on Facebook who've already gotten to the United States."

Cuban migrants start with an advantage others can only dream of: Many countries along the route grant Cubans free passage because their government does not respond to most requests for information about illegal migrants that would allow them to be deported.

And many Cubans who run out of money along the way have access to hundreds or thousands of dollars in backup funds sent by relatives who belong to one of the United States' most prosperous immigrant groups.

Once they reach the U.S. border, they can just show up at an established U.S. port of entry and declare their nationality, avoiding the dangerous desert crossings that confront many migrants who try to avoid U.S. Border Patrol. Federal data shows 45,000 Cubans appeared at U.S. land border points in the 12 months ending Sept. 20, and at least as many are expected in the coming year.

But along the way, Cubans still must navigate jungles, rivers, at least seven international borders and countries in the grip of gangs responsible for some of the world's highest homicide rates.

Asked their secret, Cubans interviewed in shelters along Costa Rica's northern border with Nicaragua almost universally pointed to cheap smartphones, data plans and Facebook.

"We're completely, always alert to our phones," Alvarez said, gesturing to his Samsung Galaxy S3 Mini outside a border statin in northern Costa Rica, where he and some 2,000 other Cuban migrants were stuck waiting for resolution of a regional conflict set off by Nicaragua's closure of the crossing. "This is our best friend, the phone. It's always on, always ready."

The metallic "zing!" of a new message arriving in the Facebook Messenger app has become the soundtrack to this year's historic migration as Cubans consult friends further along the route for tips on bus routes, border closures, even how much to bribe the notoriously corrupt Colombian police.

"They tell you when you can get money, at what moment you can arrive somewhere, what hotel to go to," said Annieli de los Reyes, pharmacist from the eastern city of Camaguey. "In all of those things, you run less risk and go with more security and peace of mind."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.