Salute to veterans: Southeast Missourians noted in military history

Throughout the nation's history, men and women from Southeast Missouri have answered calls to military service. Many have served without fanfare, but others have gained acclaim or found their way into news accounts of their service. Among those are two men with ties to one of the nation's deadliest peacetime naval accidents and a National Guard unit that at one time was the busiest honor guard (referred to at the time as a "firing squad" because of their rendering rifle volley salutes at funerals) in the country.. ...

Throughout the nation's history, men and women from Southeast Missouri have answered calls to military service.

Many have served without fanfare, but others have gained acclaim or found their way into news accounts of their service. Among those are two men with ties to one of the nation's deadliest peacetime naval accidents and a National Guard unit that at one time was the busiest honor guard (referred to at the time as a "firing squad" because of their rendering rifle volley salutes at funerals) in the country.

Point Honda incident

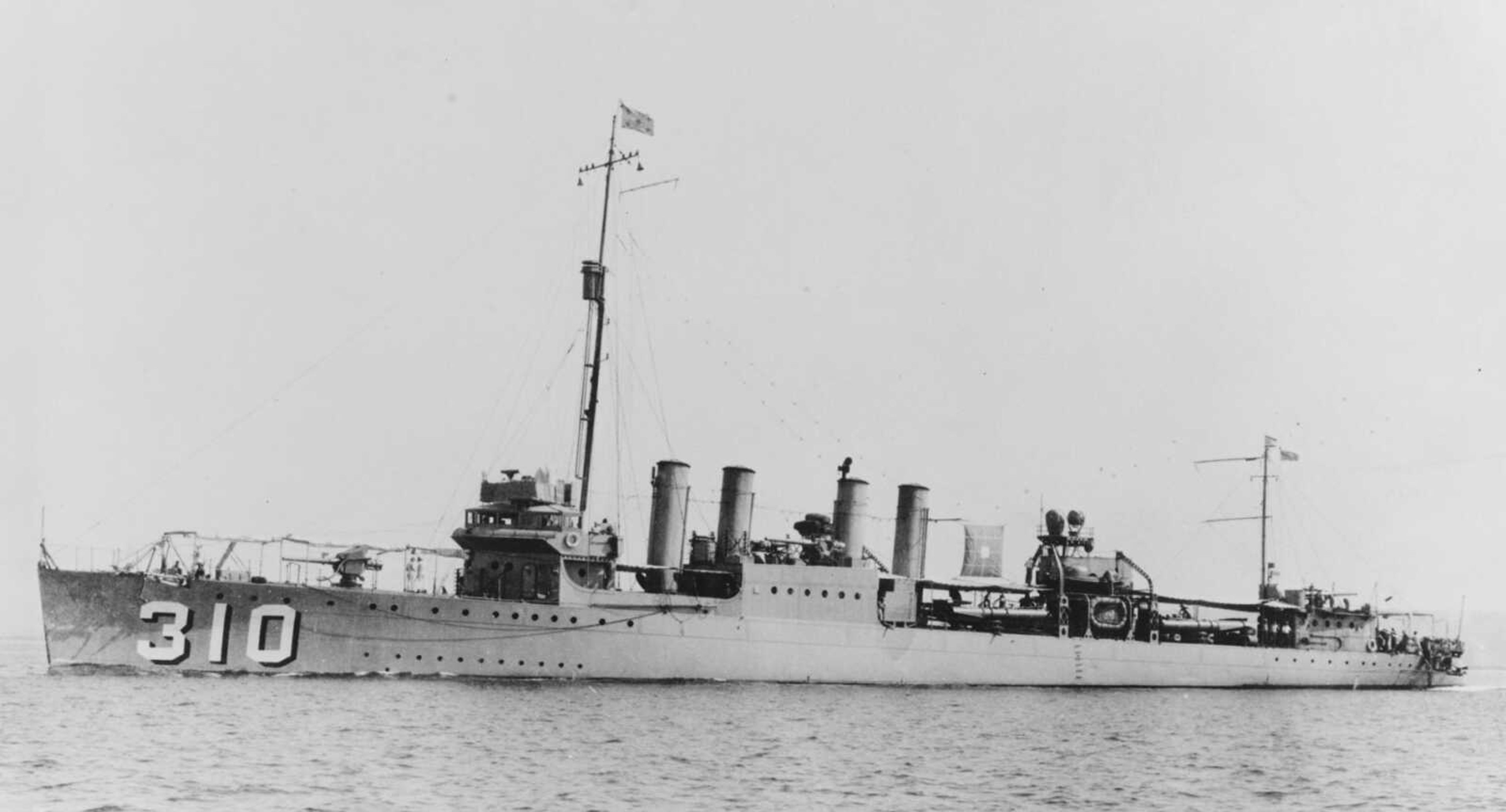

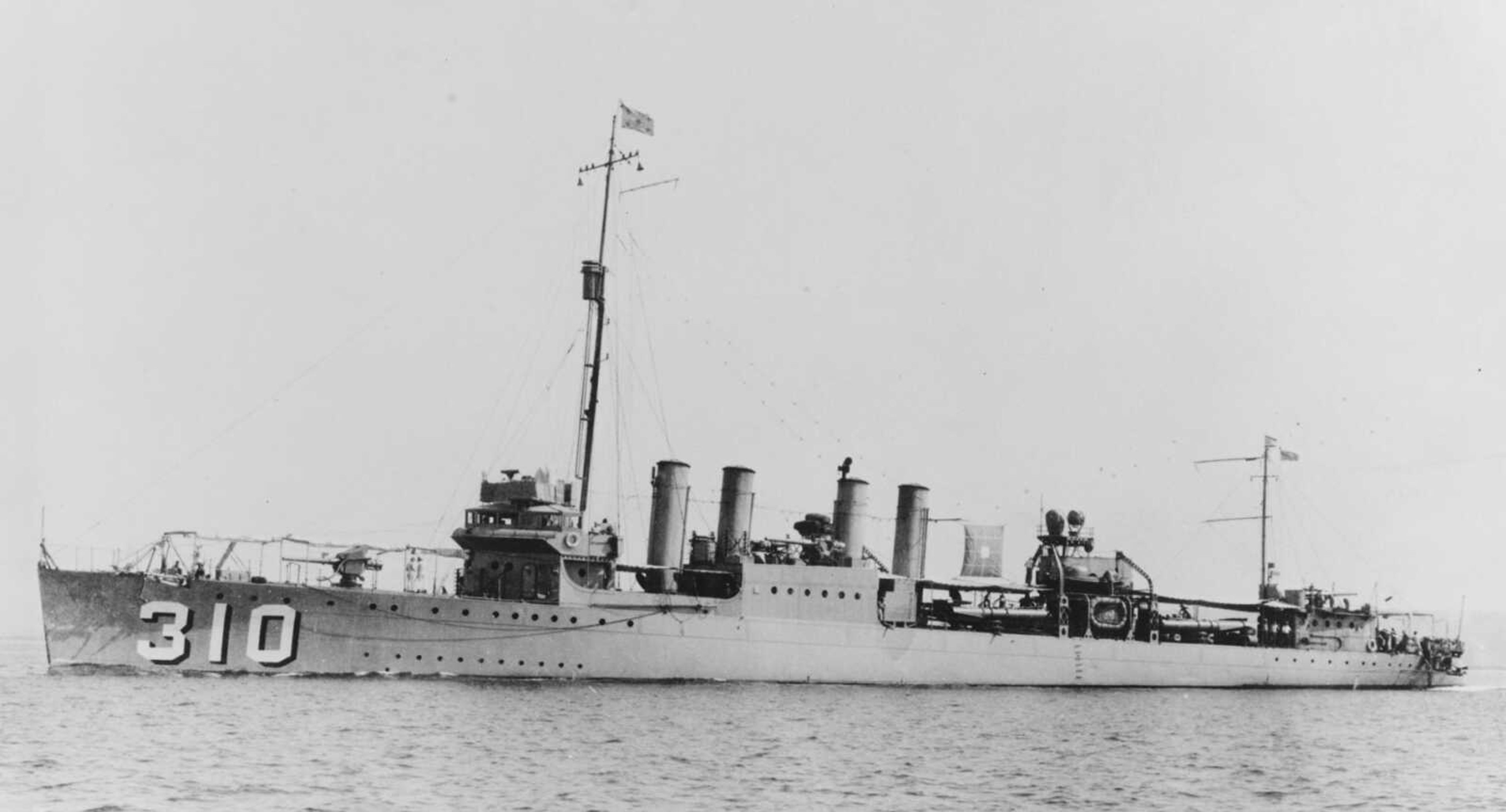

Nearly two dozen sailors died after seven Navy destroyers crashed near San Diego the night of Sept. 10, 1923.

According to the Naval History and Heritage Command: "On the morning of Sept. 8, 1923, 13 destroyers of Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 11 departed San Francisco for a two-day cruise to San Diego. They were returning home after a escorting Battle Division 4 from Puget Sound to San Francisco. The DesRon comprised the five ships of Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 33, with Delphy (DD-261) out front, followed by S.P. Lee (DD-310), Young (DD-312), Woodbury (DD-309) and Nicholas (DD-311); six ships from DesDiv 31, with Farragut (DD-300) followed by Fuller (DD-297), Percival (DD-298), Somers (DD-301), Chauncey (DD-296) and Kennedy (DD-306); and three ships from DesDiv 32, Paul Hamilton (DD-307), Stoddert (DD-302) and Thompson (DD-305). The warships conducted tactical and gunnery exercises en route, including a competitive speed run of 20 knots. Later in the day, as weather worsened, the ships formed column on the squadron leader Delphy. That evening, around 8 p.m., the flagship broadcast an erroneous report, based on an improperly interpreted radio compass bearing, showing the squadron' position about 9 miles off Point Arguello. An hour later, the destroyers turned east to enter what was thought to be the Santa Barbara Channel, though it could not be seen, owing to thick fog. Unfortunately, a combination of abnormally strong currents (caused by the extremely severe earthquake in Japan on Sept. 2, which destroyed much of Tokyo and Yokohama) and navigational complacency led the squadron onto the rocks off Pedernales Point, near Honda, just north of Point Arguello. Just after turning, Delphy struck the rocks at 9:05 p.m., plowing ashore at 20 knots. She was followed by S.P. Lee, which hit and swung broadside against the bluffs. Young piled up adjacent to Delphy and capsized, trapping many of her fire and engine room crew below. While Woodbury, Nicholas and Fuller struck reefs and ran aground offshore, Chauncey ran in close aboard Young. Alarm sirens slowed Somers and Farragut enough so they just touched ground before backing off while the five other destroyers steered completely clear. Although seven destroyers were eventually wrecked by the pounding surf, the slow, cumulative damage gave the crewmen time to escape. Rescue parties were organized, small boats and local fishing boats picked up swimmers, and life lines strung to shore allowed the rest to wade to safety. Despite delays — the last sailors were not rescued until the afternoon of Sept. 9 — only 23 men were lost, 20 in Young and 3 in Delphy."

Newspaper accounts of the incident chronicle the involvement of Joseph Smith of Cape Girardeau and Arthur Peterson of Poplar Bluff, Missouri.

n

"Girardeau Boy in Ship Wreck; Wires His Mother He is Safe"

Sept. 11, 1923

Southeast Missourian

"Ship gone aground. I am safe. Letter will follow."

This was the message received by Mrs. Agnes Smith, 102 S. Sprigg St., from her son, Joseph, who was a member of the crew of the ill-fated United States Navy destroyer S.P. Lee, which went on the rocks in the Pacific Ocean late Saturday night [Sept. 8]. Twenty-two seamen from the five wrecked boats were drowned.

The message was the only word from the young Smith, and it came before Mrs. Smith had learned of the disaster.

Smith has been in the Navy only a year and was recently assigned to the destroyer for duty in the Pacific coast waters.

Divers search for bodies

LOS ANGELES, Sept. 11 — Deep sea divers prowled today through the surf-battered hulks of the seven naval destroyers wrecked off Point Arguella, "graveyard of ships", for the bodies of sailors believed entombed there.

A detachment of Navy men along shore and five tugs standing off the dangerous rocky point, are making every effort to recover the bodies of 22 seamen reported dead or missing in the wreck.

So far only three bodies are known to have been recovered. Two bodies have been identified as F. Van Shaak of the Destroyer Young and Fireman R.A. Conroy of the Delphi.

Most of the missing are believed entombed with the underwater compartments of the Young.

The seven ships are to be left on the rock. The Navy men hope to salvage only a portion of the valuable apparatus.

The general belief of naval experts is that responsibility for the crash should not be laid to human fallibility but to the unusual tidal conditions and a radio jam. Men on the naval compass station at Point Arguella say that although they were to have given the fleet its position, they were unaware that the tragedy had occurred until breathless ranchers arrived at their tower. These compass station men say that due to the method of obtaining readings, the ships and radio men calculate only in a general way where the destroyer flotilla was located.

n

"Poplar Bluff Boy is Hero of Pacific Coast Disaster"

Swims in Mountain-Like Waves to Carry Line to Boat and Save Crew from Approaching Death

Sept. 10, 1923

Southeast Missourian

LOS ANGELES, Sept. 10 — The pounding waves of the Pacific are slowly breaking up the seven Navy destroyers that piled up high on the jagged rocks of Point Arguella on Saturday night and caused deaths of between 20 and 25 members of the crews. The exact number of sailors drowned cannot be determined. The sea is running heavy, possibly due to the earthquakes.

Racing full steam ahead at 20 knots through an impenetrable fog, the destroyers Delphy, Young, Chauncey, Woodbury, Fuller, S.P. Lee and Nicholas crashed on the rocks. Believing themselves 8 miles offshore, the boats piled up like sheep following a leader. Each one was steered by the light of the boat ahead. They lie today on the treacherous point near Santa Barbara where they probably will be completely destroyed. Only one fame, a foremate named Conroy of the Delphy, has been officially listed as dead by the Navy Department. His body has been recovered. Nineteen men of the crew of the Young have not been found. They have been listed as missing. Thirteen seamen received severe injuries.

Boatswain's mate Arthur Peterson of Poplar Bluff, Missouri, member of the crew of the Young, was the outstanding figure of the tragedy. At the risk of his life, he leaped into the sea and swam 40 yards to the Chauncey and carried a life line. Over this, 70 of the crew of the Young crawled, hand over hand, from the upturned side of the doomed vessel, to safety.

Peterson is a son of Mrs. J.W. Hulsebus of Poplar Bluff. He is 28, unmarried and has been in the Navy for several years. He telegraphed his mother these three words: "Am safe. Arthur."

Fortunately, his mother received his message on Sunday, before she had heard of the tragedy.

Before Peterson's heroic act the men clinging to the overturned Young had given up hope of being rescued.

More than 500 half-clothed gobs and officers saved from the wrecked hulks have been taken from the wild barren point to San Diego. Half dead from exhaustion, exposure and lack of sleep, they lay sprawled on the floor or on the seats of 13 train coaches and told the story of their night of terror and of the death of their comrades.

The men believe there are 20 dead on the destroyer Young alone. They think their comrades were trapped like rats in the hold of the ship when she went down beneath the surface after the crash. On the Destroyer Delphy, the leader of the squadron, three men went overboard, according to other members of the crew. One was knocked insensible and carried away on a great wave, which raked the vessel fore and aft. Another, Fireman Pearson, blinded by oil, went insane. Screaming and fighting, he tore himself away from his mates, who tried to hold him down, and leaped to his death in the surf. A third member of the crew lost his grip on the lifeline and was washed overboard.

After the Delphy struck the rocks, it was not more than an instant until the Young rammed behind her and swung against her side. The Delphy's propeller, still racing, caught the Young in the bow and aided by a big swell turned her over. Then the Chauncey piled up. The commander of the Chauncey had just a flash of warning. He ordered full speed astern when he was a few feet from the others, but it was too late. The Chauncey swung up against the Young, and the Young's propeller lifted her high upon the rocks. The other four rushed up behind within a few seconds and piled up.

The rapid disappearance of lights ahead warned eleven other destroyers that were following close behind. They escaped. Because of the proximity of the shore, however, they were unable to do much to help the others. The Young was the death trap. With her side ripped open, she keeled over in a minute and 30 seconds. She lay, bottom up, and it is believed 20 or more men were caught helpless in a compartment on the lower side under the water. This was reported by a member of her crew who escaped. Her crew and officers of the Chauncey, only 10 feet away, threw life lines over to the Young and saved many members of her crew who otherwise were sure to drown or be smashed to death against the rocks.

Watching their chance each time a swell came in, gobs lined the railing and jumped, bare-footed, to the slippery rocks. Many lost their holds but were caught by those who had made the leap. Conroy was lost when he attempted to make this leap.

The Delphy broke in two shortly afterward, The Nicholas was on a reef further out, and long into the night her crew and officers were forced to remain aboard. On account of darkness, neither lifeboat nor raft could be launched with safety.

Commander Edward Watson of the squadron stuck to his command throughout and directed the rescue work.

n

"140th Infantry Firing Squad Has Record at Serving at Rites"

Oct. 22, 1948

Southeast Missourian

Claiming the record for all of the United States, the firing squad of the 140th Infantry, Missouri National Guard, has served at 43 military funerals since it was organized a year this month. The squad, commanded by Lt. Harold E. Carr of Cape Girardeau, is much in demand, and in the past five days served at three services of last rites.

Included in the total number of funerals where the squad performed the military ritual, among the highest military honors accorded, were those services for 34 returned dead of World War II. Also, it has officiated at services for one veteran of the Spanish-American War, several World War I veterans and a number of veterans of the most recent conflict who died in the States.

22-Man Panel

The eight-man firing squad is drawn from a group of 22 men in Headquarters Company and Service Company. Each man is armed with a Springfield .03 rifle loaded with blank cartridges.

During its period of service, the squad has performed in the rain, standing in mud to the men's ankles, in blazing hot sun and in piercing cold. It serves at the graveside and at the request of the family forms an honor guard at the casket in the church and stands at attention during the entirety of the service.

One member of the squad, while standing at stone-like attention for close to an hour while the presiding minister concluded the service in a church on one of last summer's hottest days, turned white and virtually passed into unconsciousness. At the service's end, the rifle was pried from his hands, and the ill man taken outside and revived.

The squad, which has received commendations from both the local posts of the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, has traveled throughout Southeast Missouri. Lt. Carr said they have not refused any requests to serve.

Have Gained Record

Appearing in a recent publication of the National Guard was an article declaring that a squad from a New York state National Guard unit held the nation's record, having served at funerals from 18 returned war dead. This figure compares with the 43 of the local firing squad. Lt. Carr, a veteran of 30 months of service in the Pacific area, has commanded the squad at all funerals in served, except three that took place while he was attending infantry school at Fort Benning, Ga.

The squad's first assignment was at dedicatory services Oct. 12, last year, for the planting of the Cape LaCroix Cross northwest of the city. Since that time, they have been called on continuously.

The graveside ritual consists of the squad forming two, four-man ranks on either side of the rear of the hearse, and the men present arms as the casket containing the remains passes and also as the family passes toward the grave.

In Two Ranks

The squad re-forms and marches to the grave, where it takes up its position in two ranks, one behind the other and facing the grave. Lt. Carr's first command is "port arms". then to his command, "Prepare to fire three volleys", the front rank of four men does a half right face and each man takes a 12-inch step to the rear with his right foot. The second rank does a half right face as well as the 12-inch step backward with the right foot. In this manner, the men are staggered, and the rear rank of men will not be firing near the heads of the men in the front rank.

The next commands are "load" and "ready" and "aim", followed by the preparatory command "squads", and then Lt. Carr gives the command of execution, "fire".

Following the firing of three volleys, the command is to recover, and the two ranks re-form, and then the order to "order arms" is given. At the first note of taps, the order is given to present arms, and following taps, the squad responds to "order arms", completing the ritual.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.