Salute to veterans: Memories of war: WWII veteran shares combat stories

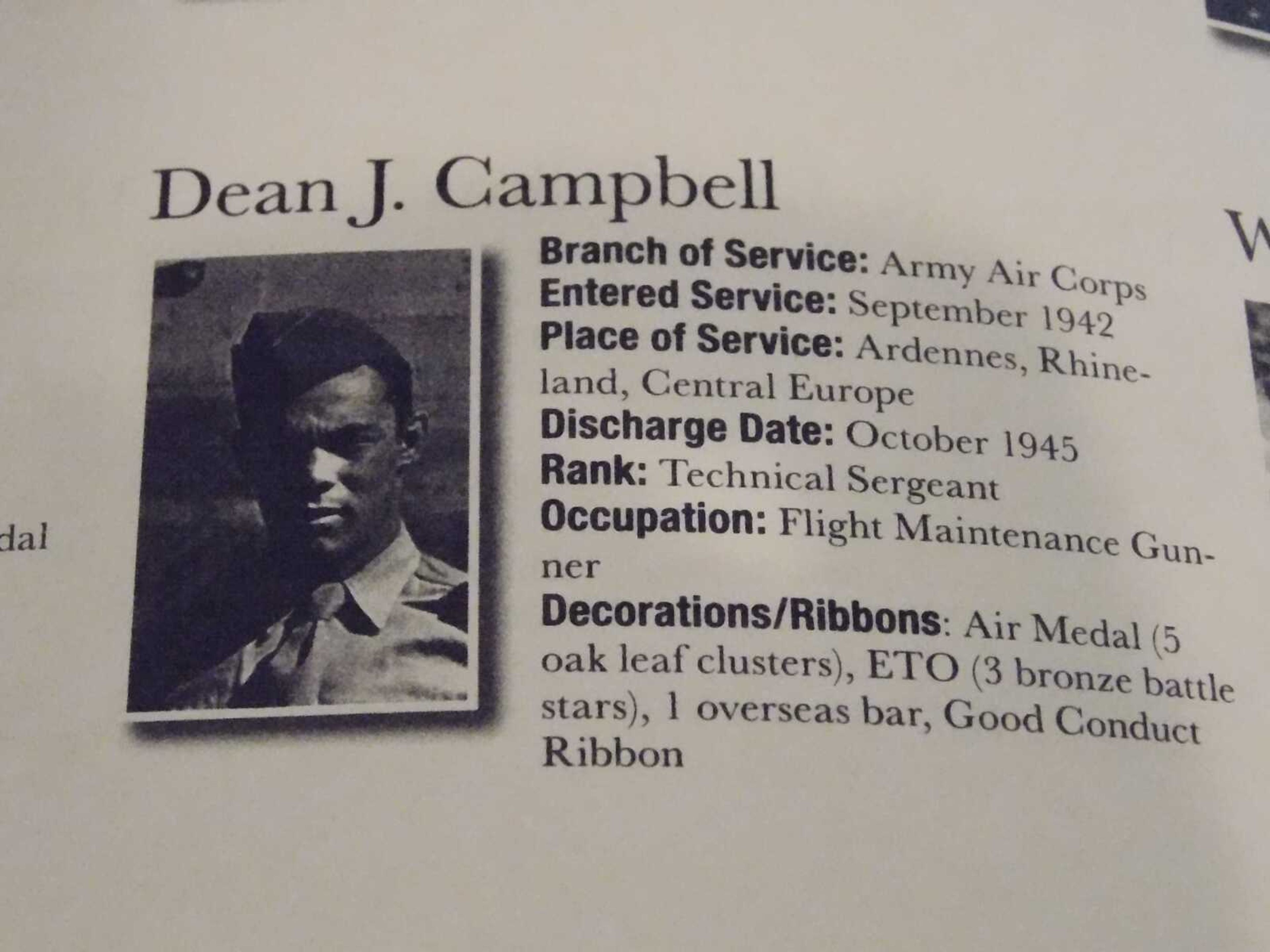

WWII veteran Dean Campbell, 99, shares vivid memories of flying 35 combat missions over Germany without a scratch. From near-misses to meeting Jimmy Stewart, his story offers a unique glimpse into history.

Dean Campbell is 99 years old and sharp as a tack. He'll be the first to admit he can't see or hear as well as he used to, but his memory is infallible.

"It's just luck," he said. "It just happened. Why, I don't know."

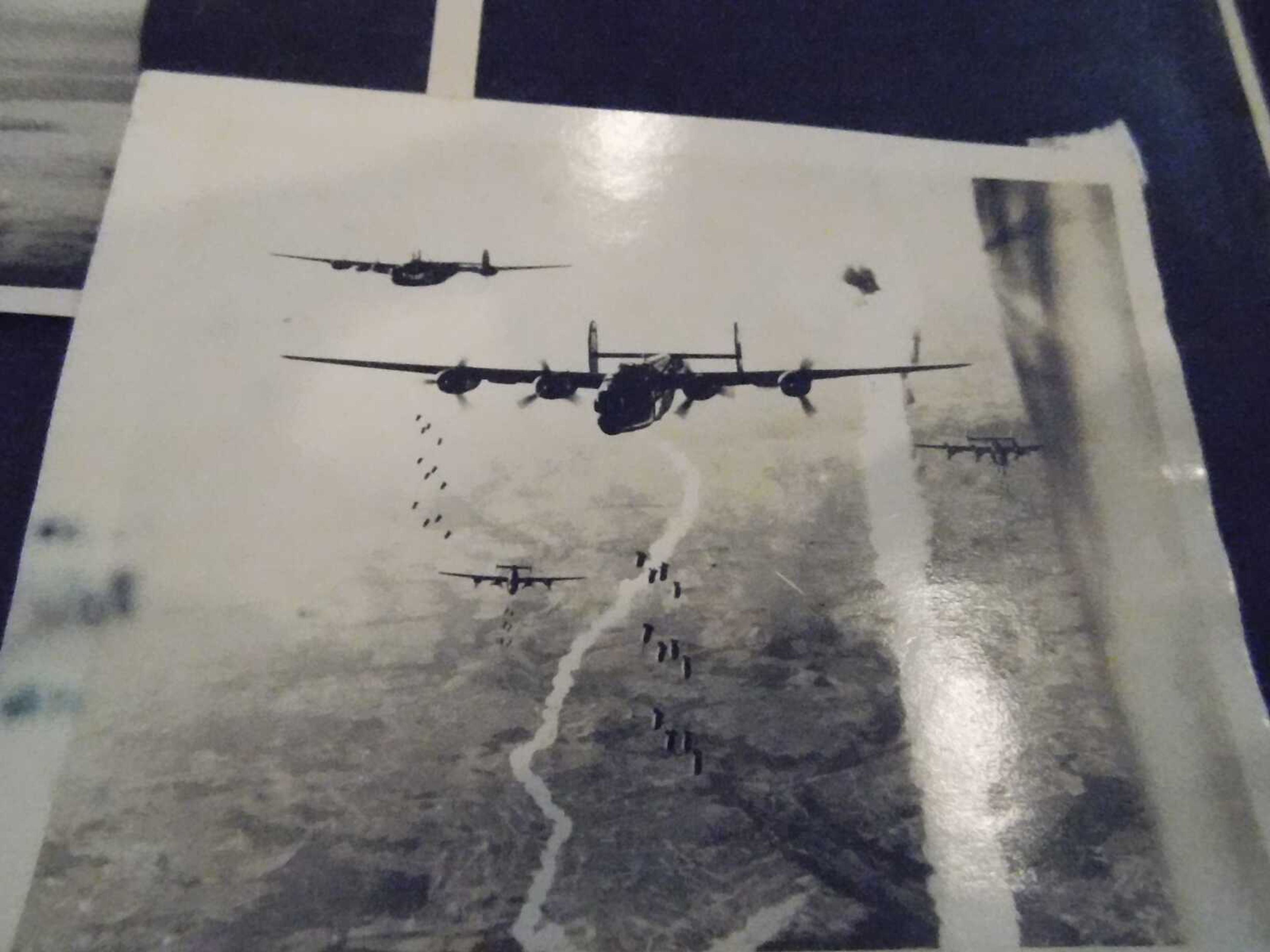

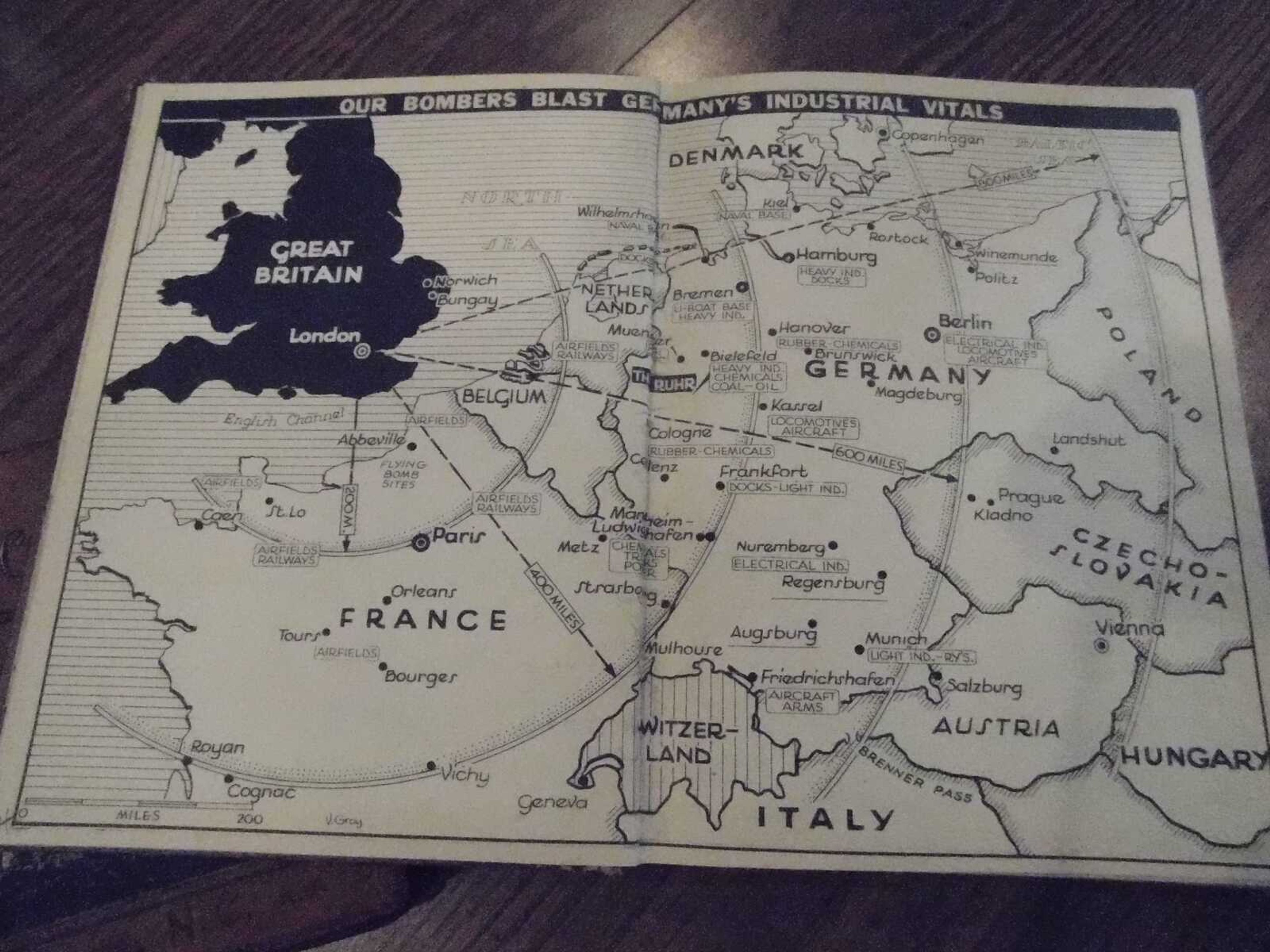

The same could be said of his experience in World War II. Campbell, a Cape Girardeau resident, flew 35 combat missions over Germany in a B-24 "Liberator" bomber.

He didn't suffer a single scratch throughout his three years and one week of service.

Campbell joined the U.S. Army Air Corps on Sept. 26, 1942, despite not knowing how to fly. He was 18 years old and said he simply wanted to do his part for his country.

"I guess you'd call it patriotic," he said.

He was assigned to the 707th Bombardment Squadron of the 446th Bombardment Group — "Bungay Buckaroos". Working in nine-man teams, these bomb crews quickly switched from targeted runs to scorched-earth bombing during the war.

"If you bomb an airfield, you've got runways, towers, hangars ... if you drop a whole bunch of bombs you're bound to hit some of it," Campbell said.

Tech Sgt. Campbell served as an aircraft mechanic and a gunner. He'd been trained in bases across the United States: North Carolina for mechanic training, Florida for gunnery school, Idaho for flying lessons. Then it was off to New Jersey to get shipped over to England and the Western Front.

Engaging the enemy

Despite his years as a gunner, Campbell only ever faced the enemy in combat once. It was on one of his final missions.

Campbell's bomber was part of a 500-plane attack on a German airfield. On the return flight, his aerial convoy came under fire from a flotilla of Messerschmitt ME 262 fighters.

"I was on the top turret of the B-24, right in back of the pilot, and I could see everything back there," Campbell recalled. "We were up above the clouds, about 25,000 feet, and I could see activity back there, vapor trails, and I know that we lost anywhere between two and four B-24s. When you lose one of those, you've got at least nine men in each one."

The German fighter planes attacked the American bombers from above. The small fighters were faster than the bombers, attacking at 400 miles per hour, while the bombers couldn't push past 250 MPH.

However, the ME 262s soon ran out of ammunition. The Americans couldn't fire back, however, because any German plane they brought down would fall right on top of another B-24.

Once a German fighter broke formation, Campbell fired his first and last shots of the war. His armor-piercing incendiary bullets found their mark, tearing into the opposing aircraft's fuselage.

But the plane did not go down.

"Say you've got a shotgun or something and you're standing on the side of the road, and a car comes driving at 140 miles an hour. How are you going to shoot him?" Campbell asked.

He later learned an umbrella of American P-52 "Mustangs" had been covering his bombing run and they shot down the fighter he had damaged.

"That's how some of these things go," Campbell said.

Almost a memory

Campbell said his group lost more bombers in crashes than they did in combat. One of his friends died when the bomber he was in careened into another while trying to land. All 18 men aboard the planes died.

On another occasion, he was awakened on New Year's Day 1945 to what he thought was fireworks. Instead, another bomber had crashed, killing all aboard. What he first mistook as fireworks was the plane's ammunition exploding.

The winter months were the worst for casualties, he explained. In February, his group lost around a bomber a day.

Campbell was almost a casualty of an accident himself. In March 1945, he was awakened at 2:30 a.m. for a 3 a.m. briefing. His group learned they'd soon embark on a long-distance bombing run to destroy German ammunition factories.

"When you get briefed for a mission, they tell you how many aircraft you might expect, how much flak you might get, how the wind might be, how the weather might be — everything pertaining to the mission so you'll be prepared for it," Campbell explained.

Campbell's crew was given the task of photographing the bomb site to see how much damage was done. This put them at a different altitude than the other bombers, one that forced them to use up extra fuel.

Campbell's crew was running dangerously low on fuel and had to stop at an airfield as soon as they got close to the shores of England on the return flight.

One engine quit as they were making the landing; another stalled before they'd finished the runway. The B-24 "Liberator" cannot fly without at least two engines running.

Campbell had come very close to crashing, but his plane was eventually refueled and flown back to join with the other bombers.

After the war

Campbell has a slew of other memories from England. While walking the streets of London, a random Englishman informed him President Franklin Roosevelt had died. He met actor Jimmy Stewart while he prepared to head back to the United States; all he could say was "hi."

Campbell joined the Missouri Air National Guard when he got back to Missouri, but he never fought again.

"When the Korean War came, I didn't want to go through that again. I didn't get a scratch in World War II. ... I got this far, I didn't want to go no farther," he said.

He worked for Monsanto in St. Louis for 42 years and has lived the life of a retiree with his wife, Dorothy, ever since. However, he's still involved in helping churches.

"We've had a busy life, and it's been prosperous because God never forgets," he said. "He always rewards you for what you've done."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.