Redefining a shutterbug

Calling Joel Ray enthusiastic is like calling a diamond a pretty rock. Both descriptions are accurate, but far too limited. Large photographic prints from a recent visit to the St. Louis Botanical Garden sit on almost every surface in his office that can support one. They even cover his Harvard diploma...

Calling Joel Ray enthusiastic is like calling a diamond a pretty rock. Both descriptions are accurate, but far too limited.

Large photographic prints from a recent visit to the St. Louis Botanical Garden sit on almost every surface in his office that can support one. They even cover his Harvard diploma.

And before a visitor can begin asking questions about the photographs, Ray bursts forth with a story about neck surgery on a dog.

It's a fascinating story, he declares. And while he finds computer images of photos taken during surgery on the 2 1/2-pound chihuahua's neck, he's dialing the veterinary clinic in San Diego, Calif., where he performed the operation.

That intensity of purpose shows in his photography, an avocation the 54-year-old neurosurgeon took up in 2000. The Bill Emerson Memorial Bridge construction was the biggest thing in town, and Ray got interested.

He sent some of the early photos to Rep. Jo Ann Emerson, Bill Emerson's widow, and she requested that he be given special access. Now the fruits of that labor have found a statewide audience in the newly published Official Manual of the state of Missouri.

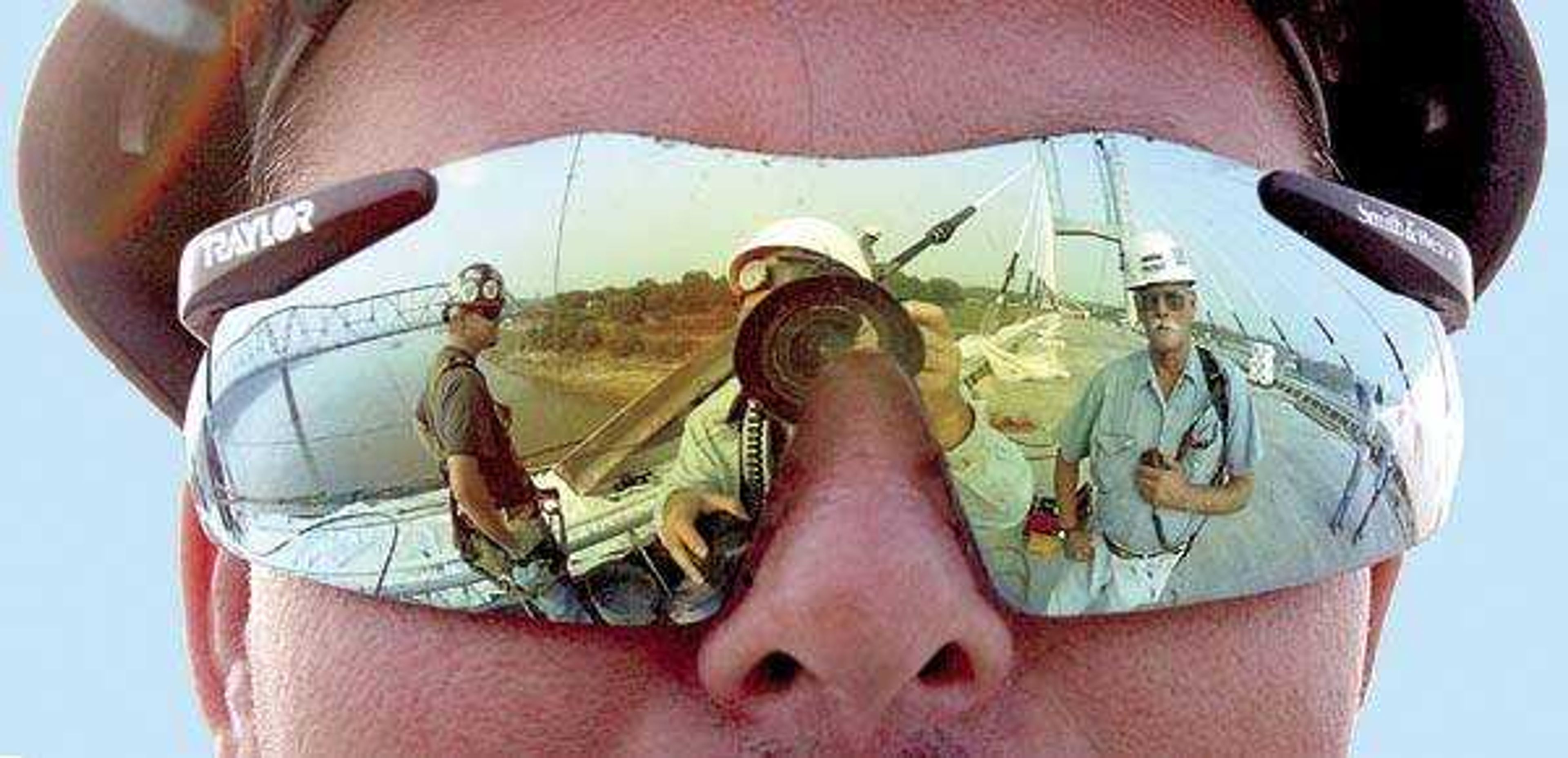

Ray's work was recognized in two categories of the biennial manual's photography contest. He won first place in the People and Architecture category and second place in the Buildings of Commerce and Industry.

"The great thing about a bridge is it doesn't move," Ray said.

He estimates he took 8,000 pictures of the bridge from the day he began using it as a subject until the final demolition of the old bridge.

Judges were impressed by Ray's submissions with their sense of perspective, said Krista Myer, director of publications for the secretary of state's office. Several hundred entries were received for the competition, she said.

The first-place photo, a close up of the reflection in a worker's sunglasses, was extremely popular with the judges, she said.

There are no prizes for the winners, Myer said, except the exposure for their work and a copy of the manual signed by Secretary of State Robin Carnahan.

The other photo in the manual sums up the entire bridge project, Ray said. "It has the old bridge, the new bridge and the workers in it."

Ray went anywhere the workers did to get his images. He was harnessed on top of a bridge tower in the middle of winter, he hung onto a crane over the Mississippi River, he rode on a boat under the bridge and flew in a helicopter over the bridge.

"They would call me up when something was happening," he says. "If I had time, I would go out for a couple of hours."

As those hours added up, so did the images. And as he began to share the pictures, Ray developed an interest in photography as a business. He's invested many thousands of dollars, created a Web site for his work and developed a plan for marketing the work.

Good photography, Ray says, needs truth, quality and continuity. The truth comes from learning the language of the camera, quality comes from taking enough time with the subject to make it understood and continuity comes from sticking with the work, he says.

"You need to facilitate a language between the subject and the rest of the world," Ray said. "The vast majority of the struggle in photography is about not giving up."

Ray didn't have to endure the hours in the cold of winter and humidity of summer to get the photos of the bridge work. As a widely recognized surgeon -- he was listed as a top doctor in spinal fusion surgery in Money magazine in 2003 -- he could concentrate on work and family. His wife, Patricia Ray, is a successful attorney; his daughter is becoming a missionary and his son is a junior at the University of Washington.

But the same joy he finds in photography draws him to other challenges, such as the recent work to help the chihuahua. He's as proud of the work he did on Roxie as he is of his photos.

Roxie is about five months old, and before surgery couldn't hold her head up.

First brought to the Animal Medical Center in San Diego, Calif., as an emergency case, Roxie was screaming in pain from what veterinarians originally thought was meningitis, veterinary assistant Dion Moffatt said.

The owners didn't want the dog. The pet shop where it was originally purchased was going to take the animal back and try to sell it again as a normal dog, Moffatt said.

She said she told the pet shop owner that was unethical, and he offered to give the dog away if someone would take her.

"I don't know how I got attached to her," Moffatt said. "It was just in her face. She wanted to live and be wanted."

Finally diagnosed as a congenital defect of the spine, his long-time friends at clinic called Ray.

Using a Synthes plate developed for humans, he fused two vertebrae. Now, Moffatt says, Roxie is starting to walk without pain while leaning against a wall.

Ray donated his time for the operation. And he took some pictures. About 8,000 during the weekend in San Diego, he estimates.

Asked about whether the expense of such surgery is justified to save a small dog, Ray calls in his office transcriptionist, Brenda Sanders. He's almost giddy as he brings in Sanders to talk about Roxie or dials the Animal Medical Center to get word about the dog.

"You can't say it's just a dog," Sanders squeals as Ray displays a picture of Roxie and Moffatt on his computer. "It's a baby."

One of the only images of Ray among his photos is the camera lens, hardhat and shirt visible in the first-place photo of the reflection in a worker's sunglasses. But that's about as close as he's been to getting into his photos.

He puts his focus, he says, on the work he does or the reaction it receives.

"I am not the subject," Ray said.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.