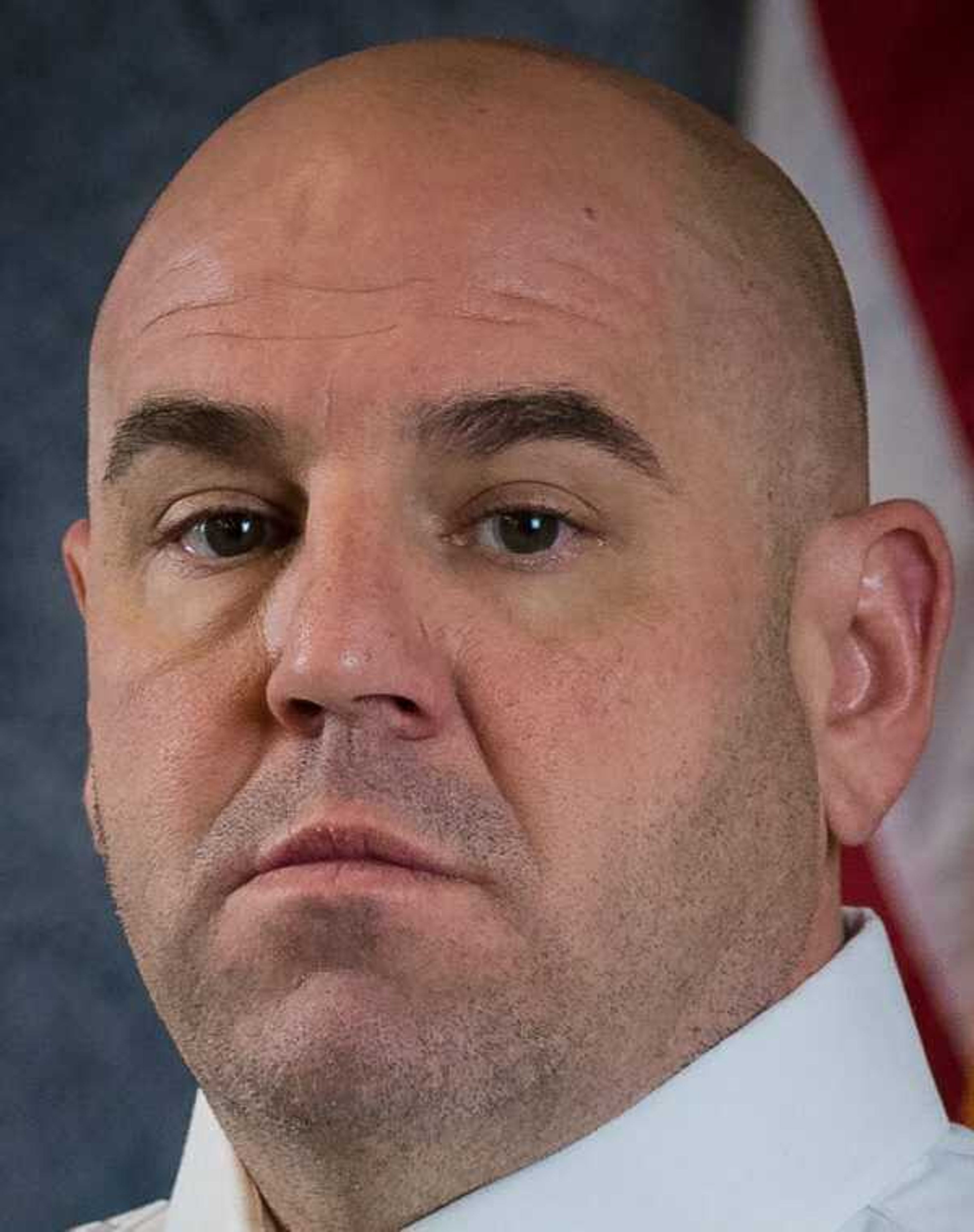

Prosecution, defense rest cases in trial for former Sikeston police officer

POPLAR BLUFF, Mo. — A Missouri State Highway Patrol collision reconstruction investigator testified that former Sikeston (Missouri) Department of Public Safety Capt. Andrew Cooper Sr. pushed his accelerator to the floor, fish-tailed, regained control, drove through a stop sign and then plowed into a Chevy Equinox, killing one of the passengers...

POPLAR BLUFF, Mo. — A Missouri State Highway Patrol collision reconstruction investigator testified that former Sikeston (Missouri) Department of Public Safety Capt. Andrew Cooper Sr. pushed his accelerator to the floor, fish-tailed, regained control, drove through a stop sign and then plowed into a Chevy Equinox, killing one of the passengers.

Ultimately, this testimony, given Thursday, June 8, as well as blood-alcohol content evidence are two crucial elements at the heart of several felony charges against Cooper that resulted in Abigail Cohen’s death Feb. 29, 2020. The prosecution rested its case against Cooper on Thursday. The defense also rested without calling any witnesses. Closing arguments will be given Friday morning.

The collision investigator, Joseph Weadon, testified that based on the vehicle’s event data recorder, Cooper was going 90 mph one second before impact, about the time he hit the brakes of his Dodge Charger Hellcat. At multiple times coming around the corner on Salcedo Road in the seconds before impact at Columbine Street, the accelerator was fully engaged, with speeds reaching 90 mph in a 45 mph speed zone.

Cooper’s defense attorney Travis Noble fought against Weadon’s testimony in an attempt to convince the jury the collision occurred at a different location than the patrolman’s determination, and that the driver of the Chevy Equinox, Christopher Cohen, was at fault for the crash due to inattention.

Thursday marked the third day of the trial, in which Cooper faces charges of driving while intoxicated with the death of another not a passenger, armed criminal action, first-degree involuntary manslaughter and three counts of DWI with serious physical injury.

Noble presented the theory that Christopher Cohen’s vehicle had cleared the intersection when Cooper struck the vehicle. Noble claimed Cooper, trained in high-speed driving situations as a police officer, could have accelerated in an attempt to miss the vehicle. The defense attorney also focused on the information presented that the “black box” readings from Cohen’s vehicle did not show the vehicle at a complete stop, but rather rolling through at 2 mph. Noble said Cohen had previously testified that he didn’t look left at the three-way stop as he was pulling through the intersection.

Weadon acknowledged that he didn’t interview Cohen or the driver or passengers in the Hellcat as part of the investigation, which would have provided a more complete report, but he stood firm on his determination that tire marks, along with the beginning of a trail of fluid beginning at the tire marks, show the collision happened after Cooper blew past the stop sign. He said he did review video interviews taken by other investigators. He also testified that Cohen was making a legal left turn when struck by Cooper’s car. The evidence from both vehicles’ data, as well as tire marks and fluid patterns, determined that Cooper, not Cohen, was at fault for the wreck. Weadon provided charts for the jury that were created using the data information, as well as drones.

Weadon also testified that even had Cohen stopped for a half-second rather than rolling at 2 mph, it would have affected his position by only 1.5 feet, and the collision still would have occurred. Weadon said there was no evidence Cohen had crossed into Cooper’s lane, as suggested by Noble.

Noble argued the accident scene was tainted by fire department hoses dragged across the area, and the fluid pattern, which helped establish the point of contact, could have been water from the fire truck, a notion Weadon refuted. Noble also tried to establish that Weadon tried to build his findings to fit the narrative created by the arresting officer, James Cooksey of the Patrol. Cooksey was not called to testify by the prosecution. It appeared Noble was trying to establish that Cooksey and Andy Cooper’s brother, Bud Cooper, a longtime Missouri trooper before retiring and being elected as sheriff of New Madrid County, may have butted heads during their careers. Weadon distanced himself from Cooksey, saying his findings were not influenced by the arresting officer.

The prosecution also presented evidence regarding Cooper’s alcohol test results. Jeremy Jones, a criminalist with the Missouri State Highway Patrol Crime Lab, testified that Cooper’s blood alcohol content, the percentage of alcohol in a person’s bloodstream, was 0.049% three hours following the wreck, which he said would have put the reading in a range between 0.084% and 0.136% at the time of the wreck. The extrapolation estimation is based on the range of average people’s elimination of alcohol over each hour. A person is considered legally drunk at a blood-alcohol reading of 0.08%.

Noble attacked Jones’ calculation by arguing that the numbers can fluctuate depending on the last time the individual consumed alcohol and how much was consumed. He said the time when a body stops absorbing alcohol and begins eliminating it affects the BAC algorithm. The absorption rate is affected by the known times and quantity of consumption.

Jones stated there was scarce reliable information regarding the amount of alcohol Cooper consumed that night. Noble said the two passengers in the car, as well as prior statements by Cooper, testified that Cooper had one and a half to two beers before they took off in the car that night, which should have been reliable enough to put into the equation. Noble argued such information may have pushed the BAC below the legal limit.

However, Jones also testified that two drinks would put a normal person’s BAC in the 0.04% range up to an hour after consumption, but the number was nearly 0.05% three hours after the collision, meaning the witnesses’ and defendant’s statements regarding two beers was likely inaccurate and not reliable. Cooper’s son, whose name is Andrew and who was one of the passengers in the vehicle, also testified he didn’t know how much his father drank before he and his friend, Joshua Atchley, arrived at the house after eating at a local restaurant.

Jones also cleared up a point brought to attention in testimony Wednesday when trooper Justin Johnson said the Missouri State Highway Patrol had changed its policy regarding blood draws for alcohol tests. Noble had said Johnson ignored a judge’s search warrant demand when he did not take two vials 30 minutes apart. Noble accused Johnson of taking it upon himself to ignore the judge’s orders.

On Thursday, Jones, with the crime lab, said the patrol’s policy regarding the 30-minute delay between draws changed in 2019. He testified the extra vial is

not needed due to the reliability of the extrapolation formula.

Legal definitions

- Involuntary Manslaughter

A person commits the offense of involuntary manslaughter in the first degree if he or she recklessly causes the death of another person. The offense of involuntary manslaughter in the first degree is a Class C felony, unless the victim is intentionally targeted as a law enforcement officer.

- Armed criminal action

Any person who commits any felony under the laws of this state by, with, or through the use, assistance, or aid of a dangerous instrument or deadly weapon is also guilty of the offense of armed criminal action and, upon conviction, shall be punished by imprisonment by the department of corrections for a term of not less than three years and not to exceed fifteen years, unless the person is unlawfully possessing a firearm, in which case the term of imprisonment shall be for a term of not less than five years. The punishment imposed pursuant to this subsection shall be in addition to and consecutive to any punishment provided by law for the crime committed by, with, or through the use, assistance, or aid of a dangerous instrument or deadly weapon. No person convicted under this subsection shall be eligible for parole, probation, conditional release, or suspended imposition or execution of sentence for a period of three calendar years.

- DWI

A Class B felony, if: While driving while intoxicated, the defendant acts with criminal negligence to cause the death of any person not a passenger in the vehicle operated by the defendant, including the death of an individual that results from the defendant's vehicle leaving a highway, as defined in section 301.010, or the highway's right-of-way;

A Class D felony, if: While driving while intoxicated, the defendant acts with criminal negligence to cause serious physical injury to another person.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.