Olmsted dam project survives shutdown, criticism on cost

OLMSTED, Ill. -- It was all but certain for a time, but the saga of man vs. river today continues in the muddy water of the Ohio, along a shipping thoroughfare called "America's busiest stretch of inland waterway." Just a little more than eight weeks ago, project managers with the U.S. ...

OLMSTED, Ill. -- It was all but certain for a time, but the saga of man vs. river today continues in the muddy water of the Ohio, along a shipping thoroughfare called "America's busiest stretch of inland waterway."

Just a little more than eight weeks ago, project managers with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, in preparation for a U.S. government shutdown, were preparing to stop daily operations of one of the country's largest construction projects -- the Olmsted Dam. The half-mile long locks and dam project 17 miles upriver from the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers couldn't continue without money.

The corps wasn't sure whether funding would come through with so many variables in play -- those not limited to the disagreement of political parties over the federal budget. The corps also was dealing with the project's damaged reputation because of cost estimates turned out so massively off the mark and a completion date that has missed its original deadline by more than 15 years. At the same time, to just leave it and never return seemed nearly unfathomable.

Dam history

The stretch of the Ohio River that someday will hold the completed Olmsted Locks and Dam sees about 90 million tons of goods such as coal, grain and metal products shipped on barges each year. The dam under construction sits between the Southern Illinois village of Olmsted in Pulaski County and Monkey's Eyebrow in Ballard County, Ky.

In 1988, $775 million for the project was authorized by Congress. Appropriations began in 1991, along with building of the grounds on the Illinois side of the river that would play host to the building of the specialized steel and concrete pieces needed for the 1,200-foot long twin locks along the western shore and, eventually, the dam.

A cofferdam, begun in 1993 and completed in 1995, was used to keep the river water out while building the locks, which were finished in 2002. Since the start of the project, the corps added buildings and equipment to the grounds, finished the lock approach walls, installed bulkheads, relocated a boat ramp belonging to the village of Olmsted and in 2004 began work on the dam that is being built using a nontraditional method known as "in the wet."

Dam function

The goal of the project is to replace two aging and nearly functionally obsolete locks upriver. Corps officials say the new locks and dam will "greatly reduce tow and barge delays," producing an estimated annual benefit of between $400 million and $700 million for the inland waterways shipping industry through savings of fuel, maintenance and other costs.

The dam, which is about halfway finished, will send barges over a 1,400-foot long navigable pass when river levels allow, according to the corps, and push a pool all the way to Smithland, Ky., a little more than 60 miles upstream from the confluence and holds a set of twin locks.

An example of the importance of the dam's function can be seen in Paducah, Ky., where more than 20 barge companies will use the river for future shipping, said Jon Fleshman, a corps' spokesman in the Louisville, Ky., district.

Dam funding

A fuel tax paid by the shipping industry goes toward the cost to build Olmsted Locks and Dam, as does money from the federal budget as allocated and appropriated by Congress.

Funding comes half from the tax revenue, which go through a trust fund, and half from the federal government. Though the original funding amount was set at $775 million, Mike Braden, chief of the corps' Olmsted division, said it should be noted the figure refers to 1988 dollars. That amount also was set before the corps decided to build the dam using the in-the-wet method -- still referred to as "innovative" by the corps despite construction's high cost and extended duration.

The cost has reached nearly $3 billion, and completion of the dam is set for 2020. Associated demolition of the aging upriver locks and building of dikes upriver from the dam are expected in 2024.

When the project was first planned in 1988, Congress expected it to be completed within seven years.

In 2002, the Southeast Missourian reported the project cost as $1.2 billion. Barges were expected to be traveling over the dam by 2006.

Though it came as a surprise to the corps, the spending ceiling for the project was raised to $2.9 billion in October when Congress ended the government shutdown with a budget deal. That amount is up from the $1.5 billion already authorized several years earlier.

"We were getting pretty nervous, because we certainly didn't expect to get reauthorized that way," Braden said. " ... Was it possible? Yes. But given what was going on in the country on Oct. 16, it seemed doubtful."

By October, the corps had begun to implement a shutdown plan. Braden said although actually stopping the project seemed like a worst-case scenario, at the same time the corps had never been up against higher odds for its continuation.

The corps blames the length of time used so far to build the locks and dam on congressional budgeting. They say not enough was allocated to allow them to take the steps they needed to plan and smoothly execute its construction.

The corps first alerted the federal government to the need to spend more on the dam in 2011. The resulting conversations haven't always been pleasant, but the work is getting done, Braden said, and it continues without the need to spend millions to shut the project down.

"Also, there is no option not to build this project," he said. "It's not a bridge to nowhere. If we don't finish this project, the hub of the inland transportation system gets shut down. That means huge economic impacts."

The corps doesn't believe rail or highways could be as efficient as transporting goods on the river -- and believe it is questionable whether those systems could even hold the load.

'In-the-wet'

But the corps admits an equal part of the delay and high spending levels for the project are because of the "in-the-wet" construction.

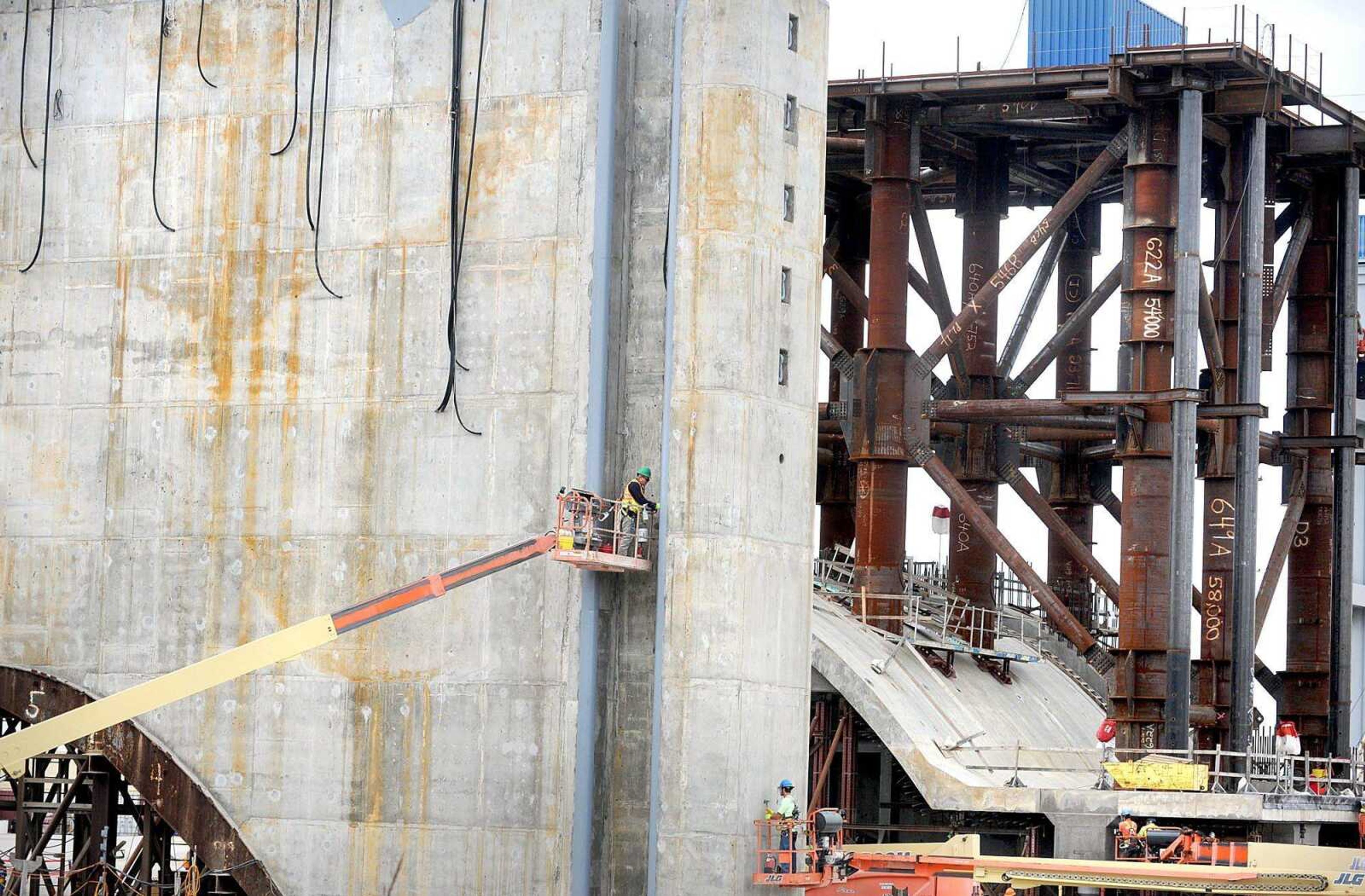

The method involves building the dam without a cofferdam -- meaning as the river flows, the dam is being set right into the middle of it. Using a cofferdam would have diverted the river as the dam was being built. Instead, multiton and multistory concrete and steel pieces known as shells manufactured in a casting yard. Each takes about seven months to build. The completed shells are floated into the river using special crane and barge equipment, then sunk. The pieces must be placed in a near-exact fit with each other. The corps then pours more than 6,000 cubic yards of concrete into the pieces to hold the dam together.

A study conducted after the project's original authorization by Congress helped determine the corps would use the method.

As for running into obstacles with the "in the wet" method, said Mick Awbrey, deputy chief of the Olmsted Division during a tour of the site last week, "this is really a research and development project. Nothing like this has ever been done before."

Dam politics and progress

Despite the project being called a "boondoggle" and "a failure" by politicians and becoming the target of many other criticisms from the shipping industry, the work goes on in Olmsted.

And last week, Braden said the corps soon was expected to get a step closer to reaching a construction milestone. On the to-do list for the corps this fall is the setting of three shells, the last of which is expected to go into the river by Nov. 30. When those shells are placed, 18 of 30 that make up the dam will be finished, leaving the corps to finish the remaining 12 for the navigable pass -- the easier part of the project.

"It's huge," Braden said. "And it helps us, too, in terms of public relations, because that's really the image people have of what's happening here at Olmsted."

The corps has to depend on agreeable flow and elevation of the Ohio River to get the work done. And if the river stays as is, said Braden, up to two more shells could be placed this season.

eragan@semissourian.com

388-3627

Pertinent address:

Olmsted, IL

Monkey's Eyebrow, KY

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.