Neighbors organize effort to oppose possible quarry

The preparations for a fight that may never take place are continuing. Rural residents near the land being considered by J.W. Strack as the location for a new limestone quarry now have a name for their opposition group, the backing of at least one state lawmaker and help from other people who blame area quarries for degrading their living standards...

The preparations for a fight that may never take place are continuing.

Rural residents near the land being considered by J.W. Strack as the location for a new limestone quarry now have a name for their opposition group, the backing of at least one state lawmaker and help from other people who blame area quarries for degrading their living standards.

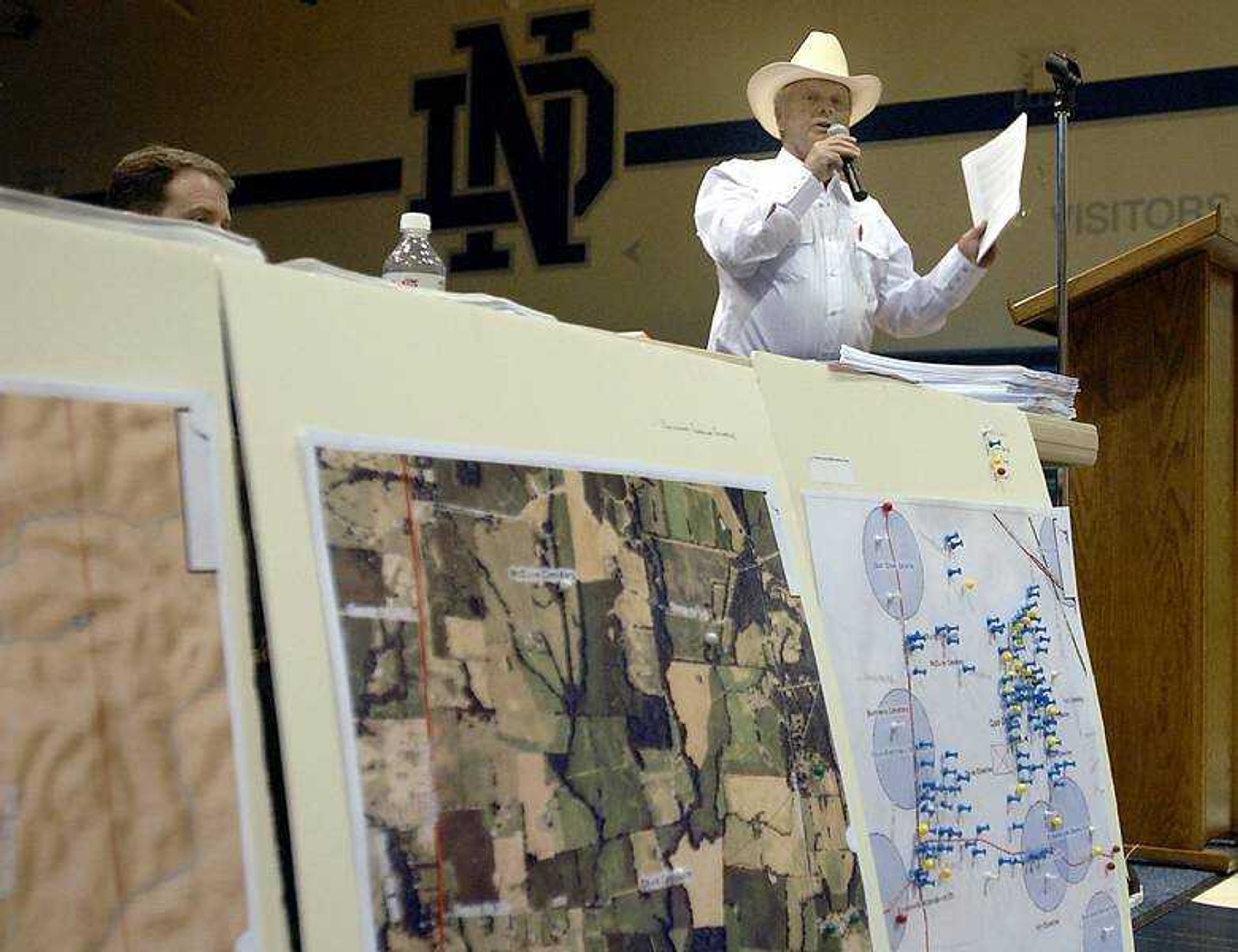

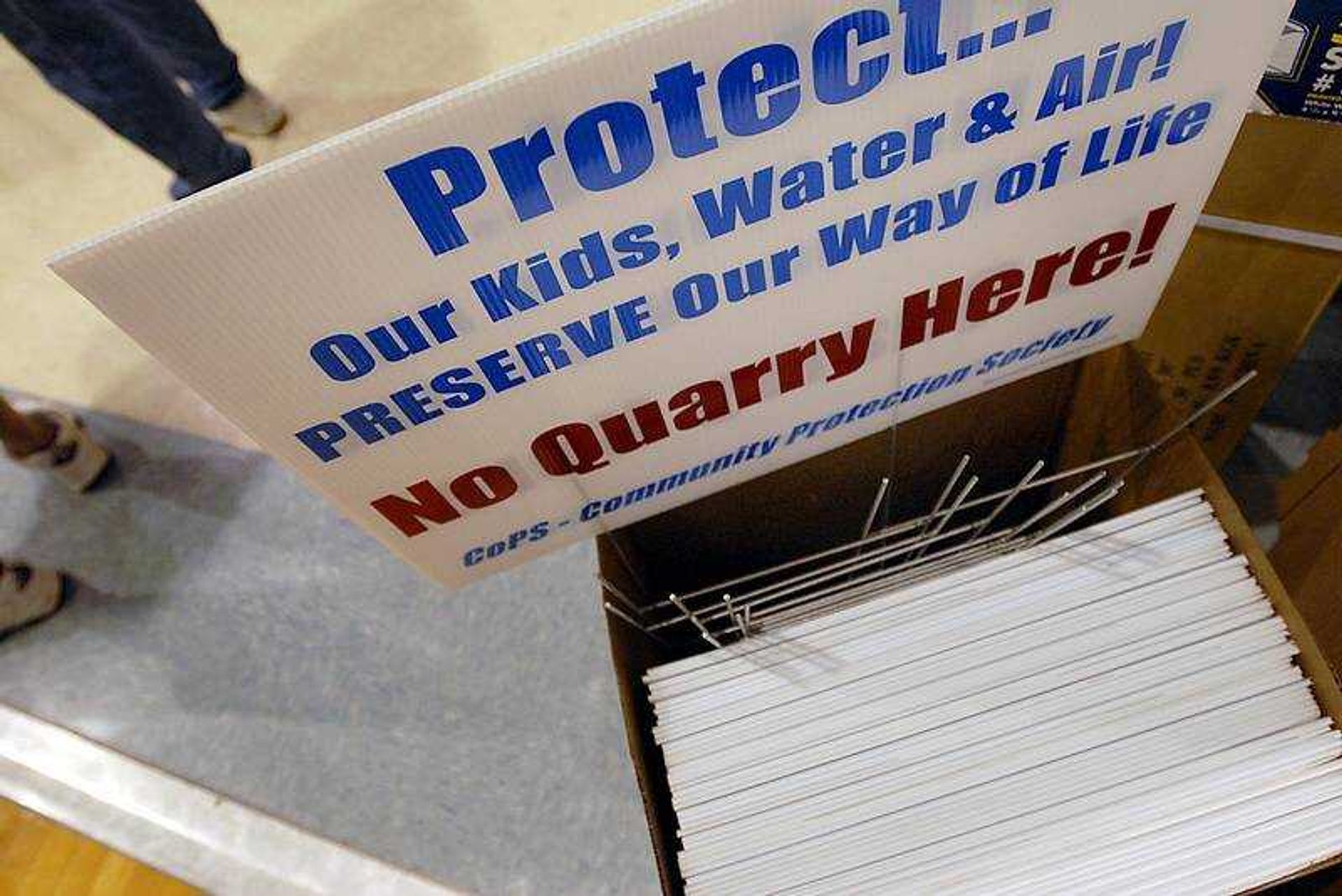

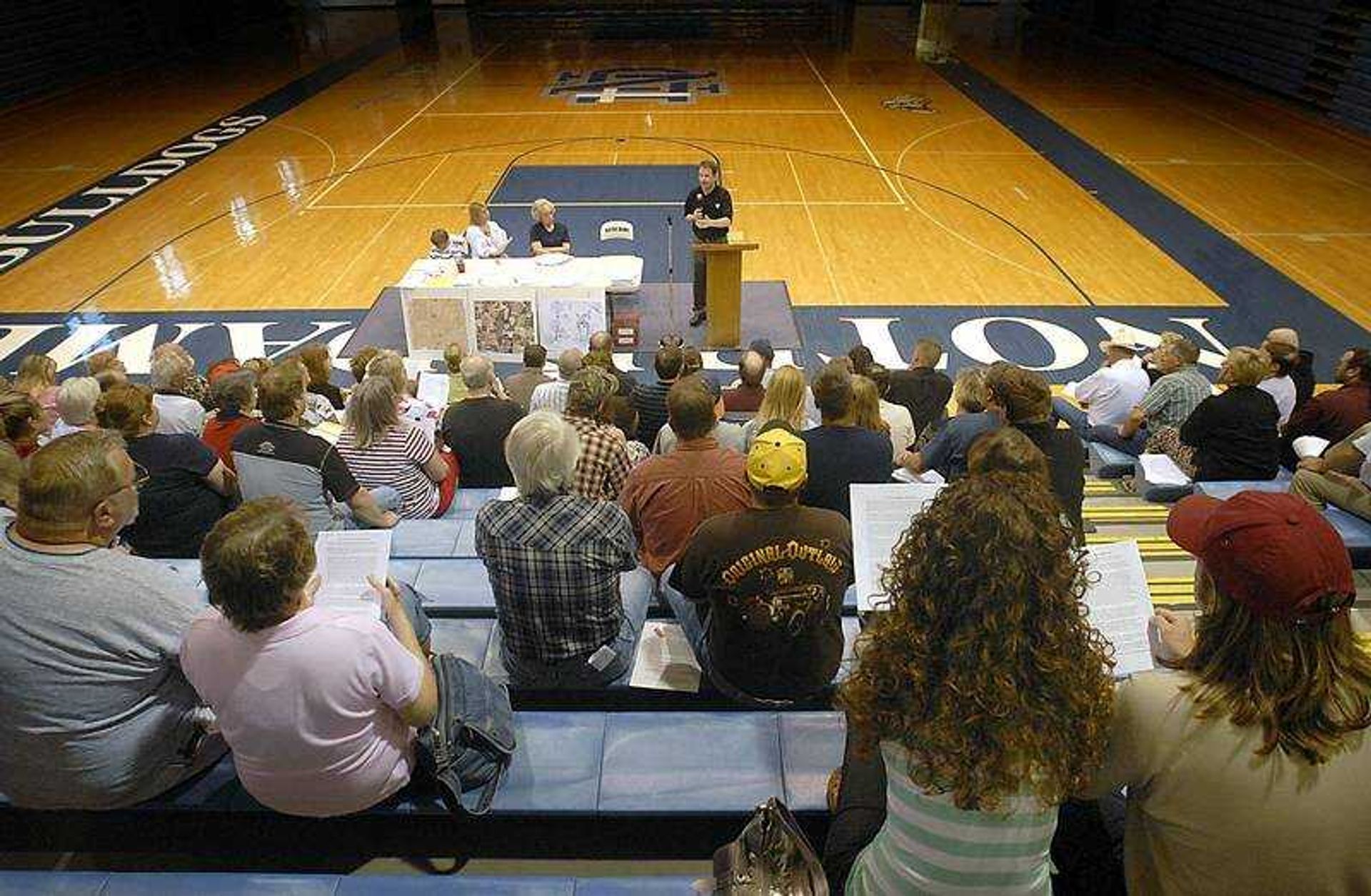

A meeting of the Community Protective Society, CoPS for short, drew more than 130 people Monday evening to the gym at Notre Dame Regional High School. They are concerned that Strack, owner of Strack Stone on Highway 74, will turn 106 acres on County Road 319 near Highway 25 into a limestone quarry. Strack said Monday evening after the meeting that he has not completed a purchase of the land, has not applied for a mining permit nor has he received a geologist's report on the suitability of the site for a quarry.

Acting now to get organized is important, said Melinda Winchester, who directed the meeting. "The reason we are doing this now is once he applies, we don't have much time," she said.

A limestone quarry needs three state permits -- one for land reclamation, one for air quality and one for storm-water discharge. The first, and most likely place to stop a proposed quarry, state Sen. Jason Crowell, R-Cape Girardeau said, is with the mining permit. Crowell had his staff research the rules of the Land Reclamation Commission for the group, and his office also faxed the group a two-page sheet entitled "The Steps to Oppose a Rock Quarry."

Crowell urged everyone in the group to start making lists of potential effects on their health, safety and livelihood. "If enough people out there tell stories, that will put us on a path to the most probable outcome of success we want," he said.

The rules and laws governing the permit process are clear: To stop a quarry, opponents must show that health, safety or livelihood "will be unduly impaired" by approval of the permit application.

Strack, meanwhile, questions whether anything he might do with the land is acceptable to the group opposing him. While he has estimated that a quarry could result in several hundred truck trips each day along Highway 25 or other area roads, a subdivision of 300 homes would bring far more traffic, he said.

"These people are the same people that don't want a subdivision or nothing but a farm there," Strack said.

Opposition to the quarry focuses on the state permitting process because, with no planning or zoning in unincorporated areas of Cape Girardeau County, there are no local land-use restrictions.

To bolster their effort, Winchester introduced Larry Miller, a cattle farmer from northern Boone County who lives near a quarry that recently expanded. Miller told of issues with how the quarry has stored dirt removed from the surface. The dirt has altered where Mississippi River floodwaters go and eroded into a nearby creek.

The quarry was a good neighbor until it changed hands and started to expand, Miller said.

Along with the state permits, Winchester told the group that research is being conducted to determine if federal permits are required -- a drainage creek could require a Corps of Engineers permit, she said, and if the Corps requires a permit, a cultural heritage survey would also have to be done.

The exceptional effort isn't a personal vendetta, Winchester said. It is aimed at the quarry, with the possibility of noise, dust and traffic that it brings, not Strack, she said.

And Strack said he's not going to get into a personal fight, either. "I am not worried about it, and I have nothing to hide," he said. "They are going to be my neighbors out there when the dust settles."

rkeller@semissourian.com

335-6611, extension 126

Were you there?

Does this affect you?

Have a comment?

Log on to semissourian.com/today

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.