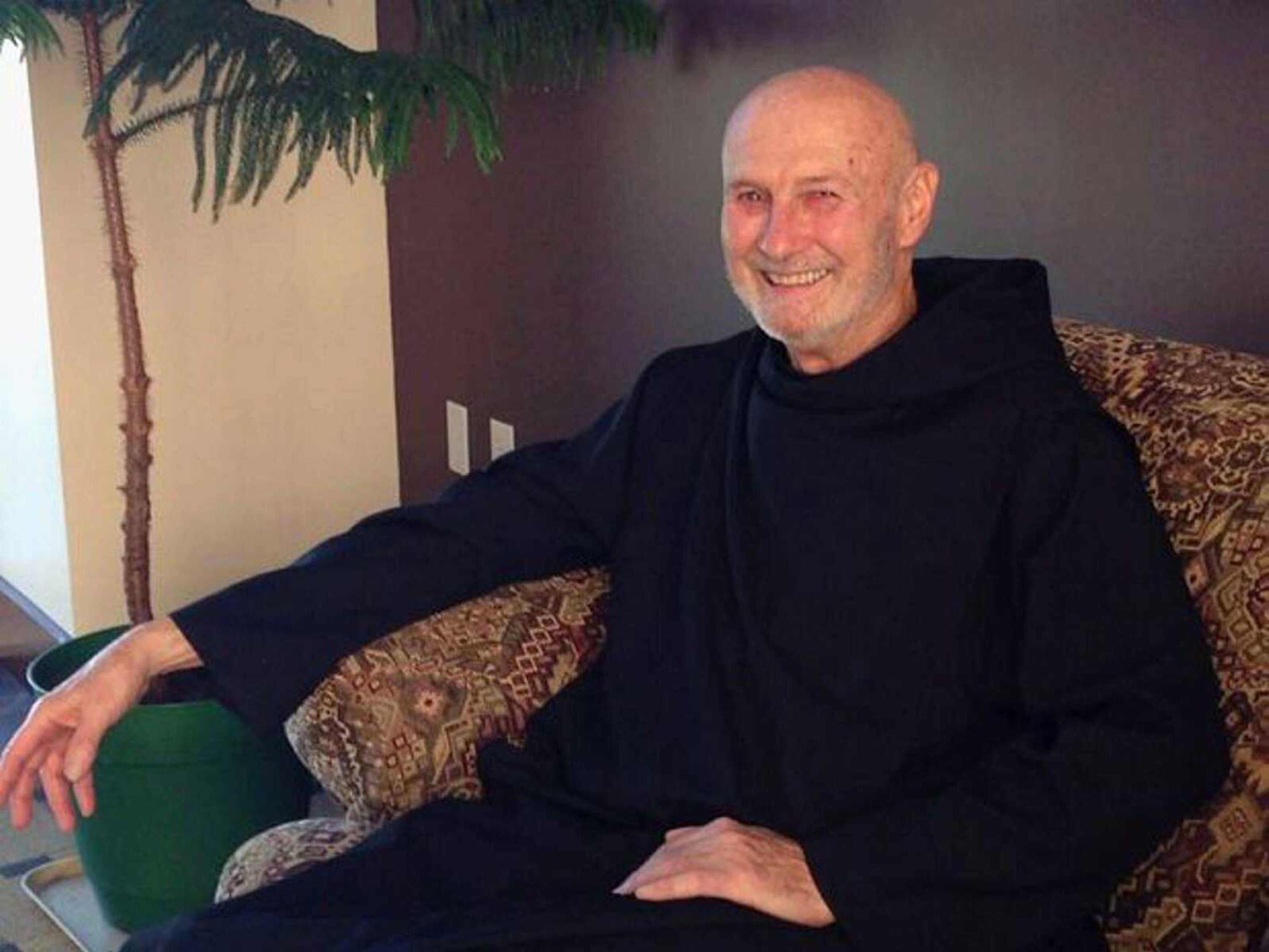

Missouri monk uses nails to make art

ST. JOSEPH, Mo. -- Where most people might see a piece of rusted, discarded metal, Brother Blaise Bonderer of Conception Abbey sees a potential work of art waiting to be created. "About 40 years ago, they tore down an old building here. ... I saw these square nails and I was fascinated by them because I'd never seen them before," Blaise told the St. Joseph News-Press. "I just started collecting a few."...

ST. JOSEPH, Mo. -- Where most people might see a piece of rusted, discarded metal, Brother Blaise Bonderer of Conception Abbey sees a potential work of art waiting to be created.

"About 40 years ago, they tore down an old building here. ... I saw these square nails and I was fascinated by them because I'd never seen them before," Blaise told the St. Joseph News-Press. "I just started collecting a few."

Inspired by a framed skeleton key display his niece had received as a wedding present, Blaise began epoxying the old nails to wood in designs such as the words "Hope," "Peace" and "Love."

"It was something very simple," he said. "I'd give it to the family for Christmas and things."

When someone suggested that he start brazing the nails, he wasn't sure at first. He didn't have any metalwork experience. Brazing requires melting a brass rod to connect the nails, which leaves a visible brass coating on the joints. He decided to try it, using an acetylene torch to melt the brass.

"I started doing that, doing simple designs," he said. "I did that for a while, and I was selling them locally and making them for family. But I sort of lost interest."

So he stopped. Thirty years later, when life afforded him more free time, he felt drawn back to the artform.

"I've always liked working with my hands," Blaise said. "I like the things of the earth."

Now, he spends an hour or two a day working on the nail art creations in the monastery's garage, Blaise said. His favorite pieces to make are crucifixes, which he makes with various types of nails and recycled barn wood.

Getting the nails, including large spikes, eight pennies and finishing nails, just kind of happens, he said. A few times, people have given him five-gallon buckets of old nails. He also has found them in old buildings at the abbey and surrounding communities during remodels or demolitions.

Most of the nails date back to the 1800s, Blaise believes. Before that, nails were hand-forged, a labor-intensive and expensive process. In the early 1800s, machines could create "cut nails" faster than hand-forging, although the process was still labor intensive. The cut nails continued to have the square head of the previous handmade nails.

"The square nail was used up until the late 1800s," Blaise said. "The straight nail we know now wasn't invented until the 1900s."

When he gets the square-headed nails, they are worn and rust-covered. He first removes the rust from each nail with an electric wire brush.

"There's always a big joke, people ask 'What are you doing?' [I say] 'Oh, I'm going down to do my nails,"' he said. "They look at my hands and ask, 'You are doing your nails?'"

After they are cleaned, Blaise brazes the nails into designs, which come from his imagination, he says. He enjoys creating crucifixes, cross pendants, wall decorations and various Christmas ornaments.

"That's the fun part, drilling that itty bitty hole in there," Blaise said, holding up a piece with a small hole drilled crosswise in a nail. Later, he will thread a ribbon through the hole to hang the ornament.

Different types of nails are better for different projects, he says. Finishing nails, which are smaller and have a small head, are best for bending and more intricate brazing work, including the rounded abstract head of Jesus on the crucifix. Bending nails is the hardest part of the process, Blaise says.

After brazing the pieces, he cleans the nails again and finishes with a polyurethane spray to prevent rust. Each piece takes between two and two-and-a-half-hours, although he breaks the process up, Blaise says. Overall, he estimates that he has made more than 40 crucifixes and many other pieces.

The pieces are on sale in the bookstore at Conception Abbey in Conception, Missouri. Additional pieces, some from decades ago, are on display in the abbey's welcome center.

They are popular with visitors, he says, but he enjoys the work for more than selling the pieces.

"It's peaceful work, working by myself," he says. "I enjoy working with my hands."

Information from: St. Joseph News-Press/St. Joe, Missouri, http://www.newspressnow.com

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.