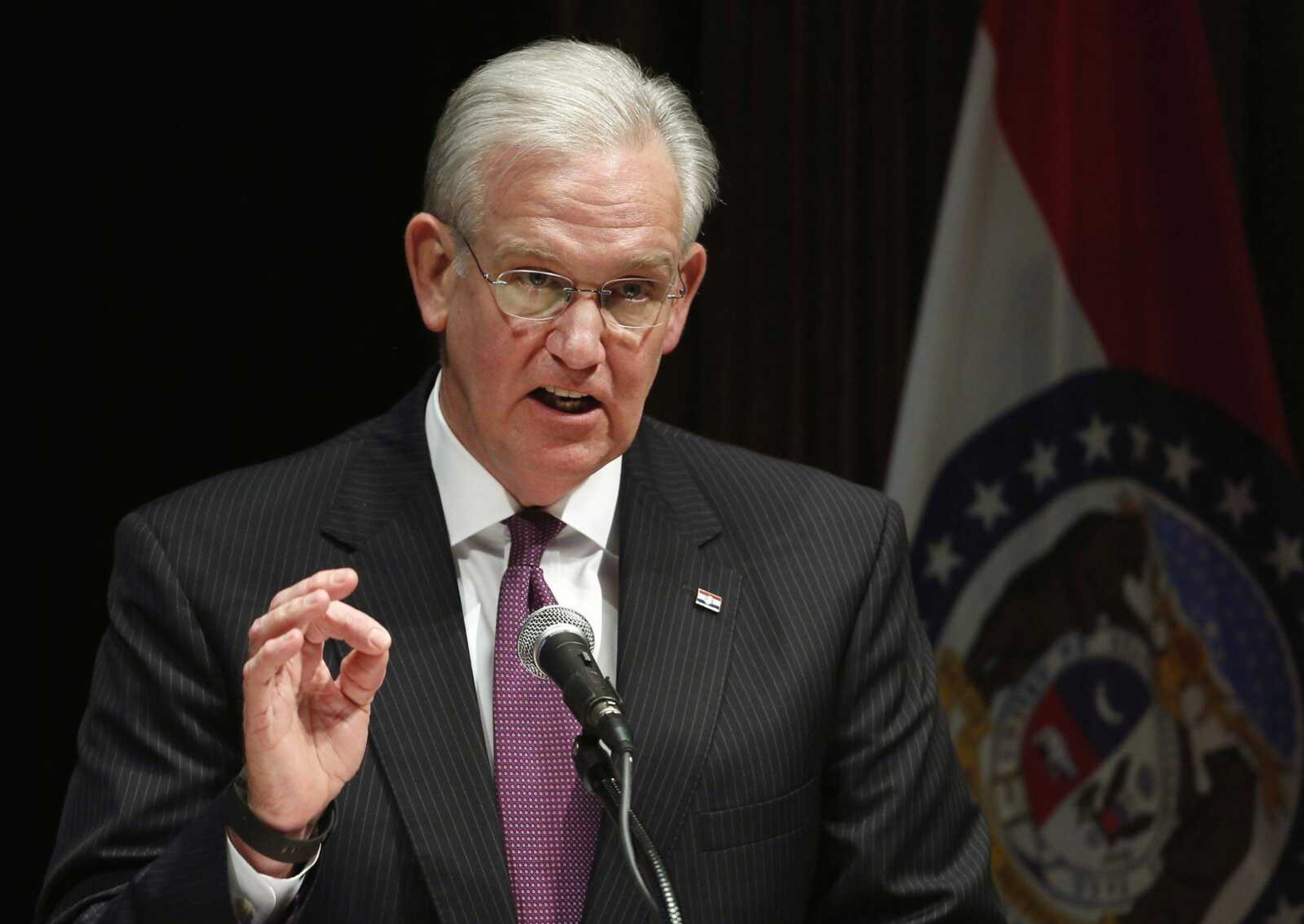

Missouri governor tops 100 pardons, including clergy protest

JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. -- For 16 years as Missouri attorney general, Jay Nixon's job was to be tough on crime. His office argued against appeals from people challenging their convictions and sentences. As he nears the end of his tenure as governor -- and a lengthy political career -- Nixon showed mercy...

JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. -- For 16 years as Missouri attorney general, Jay Nixon's job was to be tough on crime. His office argued against appeals from people challenging their convictions and sentences.

As he nears the end of his tenure as governor -- and a lengthy political career -- Nixon showed mercy.

The Democrat pardoned 18 people Friday, including 16 religious leaders convicted of trespassing for protesting in the Missouri Senate in support of Medicaid expansion. He also commuted the sentence of one person, raising his total to 110 clemency actions.

That's more than any Missouri governor in the past three decades.

Nixon's office said there will be no more pardons or commutations before he's succeeded at noon today by Republican Gov.-elect Eric Greitens.

Friday's pardons affect most of the 22 people convicted in August for their role in the May 2014 Senate gallery protest, in which hundreds of activists chanted and sang hymns while calling on the Republican-led Legislature to expand Medicaid under Democratic President Barack Obama's health-care law. Missouri lawmakers refused to do so.

Nixon's office said the other six people who were convicted did not seek clemency.

His final pardons also included William Corum, who was convicted of assault in 1984 but later founded Prison Power Ministries. The other pardon and commutation were for people convicted of drug crimes.

Nixon said he hasn't gone soft on crime, he's just operating from a different perspective.

"When you're attorney general, you're on one side of the case," Nixon said in an interview last month with The Associated Press. "As governor, it's a position of consensus and you have executive authority."

He added: "It's not that I'm a different human being; it's a different job."

Pardons restore citizenship rights, such as the ability to possess firearms or serve on a jury, and can occur long after a person has finished serving a criminal sentence. The pardoned Medicaid protesters had already been spared from jail by the jurors who convicted them. Commutations shorten the sentence of an incarcerated person. Both are a form of clemency.

Nixon's clemency actions are the most since the early 1980s, before politicians across the nation began enacting longer mandatory minimum sentences and showing less leniency toward convicted criminals.

Republican Gov. Christopher Bond approved a total of 201 clemency actions during two split terms, from January 1973 to January 1977 and from January 1981 to January 1985, according to records compiled at the Missouri State Archives. Those records show that Democratic Gov. Joseph Teasdale issued 196 clemency actions during his single term in office, from January 1977 to January 1981.

But no governor since that era had approved more than 50 clemency actions until Nixon.

An attorney, Nixon first won office as a state senator from De Soto in 1986. He won election as attorney general in 1992 and as governor in 2008.

The majority of Nixon's clemency actions have come during the end of his time as governor, and most of the pardons have been for theft or drug crimes committed years ago. In news releases, Nixon has frequently noted that the pardoned people have since become productive members of society.

"I think people deserve to do their time for offenses they commit, but (for) people who turn their life around ... mercy is a good and valuable emotion," Nixon told the AP.

Mercy once was more common from governors, though it sometimes stemmed from practicality instead of compassion. For many years, Missouri had only one state penitentiary -- located in Jefferson City -- which initially lacked space for women and often became overcrowded with men. Pardons and commutations were sometimes issued to make room for new prisoners.

From 1847 to 1930, governors issued a total of between 4,000 and 5,000 commutations, according to the state archives.

"The pardon power was used extensively in the 19th century and early 20th century -- it was very common," said Gary Kremer, executive director of the State Historical Society of Missouri.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.