Man who killed as teen kept behind bars by officials

WARWICK, R.I. -- Craig Price was a brawny teenage football player with a baby face and winsome smile who lived with his parents in a small ranch house in the Buttonwoods section of town. One summer night in 1987, he crept across his neighbor's yard, broke into a little brown house and stabbed Rebecca Spencer 58 times. She was a 27-year-old mother of two...

WARWICK, R.I. -- Craig Price was a brawny teenage football player with a baby face and winsome smile who lived with his parents in a small ranch house in the Buttonwoods section of town.

One summer night in 1987, he crept across his neighbor's yard, broke into a little brown house and stabbed Rebecca Spencer 58 times. She was a 27-year-old mother of two.

He was 13.

Two years passed before Price struck again.

Joan Heaton, 39, was butchered with the kitchen knives she had bought earlier that day. The bodies of her daughters, Jennifer, 10, and Melissa, 8, were found in pools of blood, pieces of knives broken off in their bones; Jennifer had been stabbed 62 times.

Buttonwoods was paralyzed. Police combed the streets. Neighbors padlocked their doors. The Heaton house was just a few hundred yards from the Spencer home and the question hung thick over the tidy, working-class neighborhood: What kind of monster was living in their midst?

A calm confession

The answer came two weeks later.

Price was a wisecracking boy who had been in minor trouble for petty burglaries -- "thieving" he called it -- but who seemed friendly to neighbors and was always surrounded by friends.

Police had become suspicious after he lied about a deep gash on his finger. They knew from the crime scene that the killer had cut himself. A bloody sock-print matched Price's size-13 feet. They found the knives in his backyard shed.

At the police station, his mother sobbing softly beside him, Price calmly confessed to the four murders.

Yet even as police and prosecutors celebrated the capture of Rhode Island's most notorious serial killer, they were reminded of a grim reality.

In five years, Price would be free to kill again.

Price was a month shy of his 16th birthday. As a juvenile, he would be released from the youth correctional center when he turned 21 -- the maximum penalty under Rhode Island law at the time. His records would be sealed. The 5-foot-10 inch, 240-pound killer would be free to resume his life as if the murders had never occurred.

The law was on his side and Price knew it.

"When I get out I'm going to smoke a bomber," Price yelled as he was led, handcuffed, from the courthouse.

Bending the rules

Jeffrey Pine, then assistant attorney general, said he had never felt such frustration. "There was something fundamentally wrong with a system that allowed someone who killed four people to simply go free at 21," Pine said.

And so Pine and others embarked on a mission. They would change the system so that future young murderers could be locked up for life. At the same time they would do their best to ensure that Price himself would stay behind bars long past his 21st birthday.

It was an extraordinary response to an extraordinary case and it involved every level of government, from the governor's and attorney general's offices to the state legislature, the police and the courts.

In effect, the legal system would bend the laws it was sworn to uphold because, despite misgivings by some, many believed that keeping Price behind bars was simply the right thing to do.

His own worst enemy

In many ways, the best tool to hold him turned out to be Price himself.

On the advice of his court-appointed lawyer, he refused a court order to undergo further psychological testing, fearing the results would be used to commit him for life. His refusals allowed Pine's office to file contempt-of-court charges in 1994. When Price flew into a rage and threatened to "snuff out" a corrections officer, Pine seized the opportunity to file extortion charges.

It was an indictment for what many considered routine language in the youth prison. But there was a growing public demand for action, fueled by fear of Price's imminent release.

Media reports describing Price's life behind bars stoked the fear. There were stories about how Price had beefed up to 300 pounds by lifting weights, how he boasted freely about "making history" when he was released.

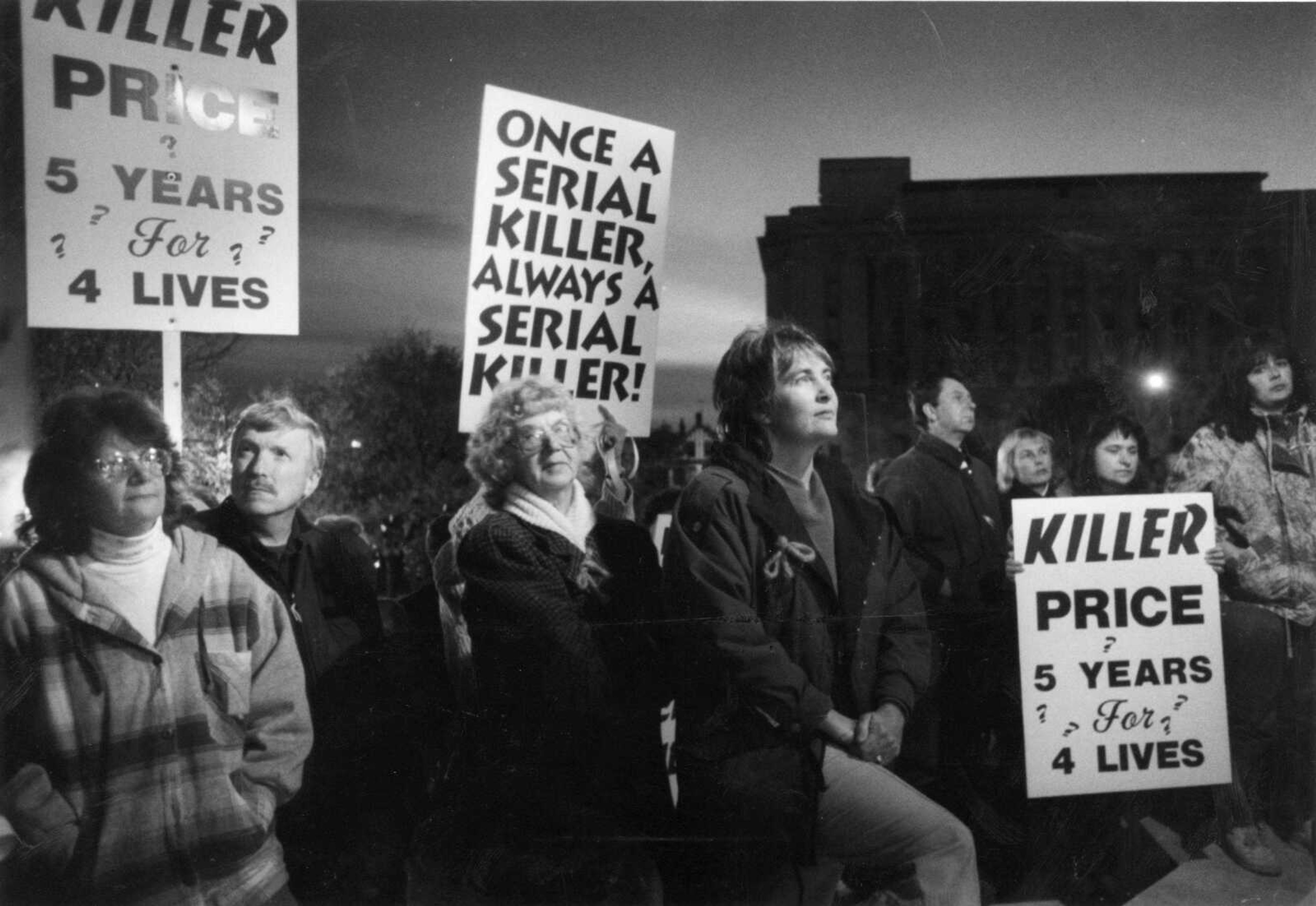

"Everyone in state government wants to blow out the candle on Craig Price and keep him behind bars," Gov. Bruce Sundlun told the crowd at a candlelit vigil outside Warwick City Hall in June 1994.

Price was sentenced to 15 years, seven to serve and eight suspended. He spent his 21st birthday in the Adult Correctional Institution.

Adding on years

For more than a decade, the state continued to find creative ways to charge and convict Price. Criminal contempt charges stemming from Price's earlier refusals to submit to psychiatric testing went forward -- and brought a one-year sentence -- even though, on the advice of Mann, Price had since agreed to the tests. Fights in prison led to assault charges. The state even took the unusual step of charging Price with violation of probation while he was in prison.

Every conviction added more time. Several appeals went to the state Supreme Court. Always, Price lost.

In May 1997 Price appeared before Chief District Court Judge Albert DeRobbio after a jury convicted him of criminal contempt. Three years earlier DeRobbio had sentenced Price to one year for the same charge, believing it was the maximum he could impose. Subsequently the Supreme Court ruled that judges had unlimited sentencing power in such cases.

Contempt charges usually result in a fine, not jail time. Yet the state was begging DeRobbio to put Price away for life.

"I did not feel that I could, in conscience, sentence him to life on a contempt charge," DeRobbio said.

And so he gave 25 years, 10 to serve and the remaining 15 years if Price got into trouble or refused treatment.

Price's legacy

"The state was effectively organized not to rehabilitate me, but to incarcerate me," Price complained in court in 2004.

Many felt that was true, but that the state had no other choice.

There is no doubt that Price left a lasting legacy on the juvenile justice system in Rhode Island. Today, a 15-year-old serial killer would immediately be referred to adult court and likely sentenced to life without parole.

Price's current scheduled release date is December 2020. He will be 46.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.