Lessons after college

WASHINGTON -- Victoria Grossmann graduated from the University of Florida in 2003 with a degree in business, a minor in statistics, big plans -- and about $5,000 in credit card debt...

WASHINGTON -- Victoria Grossmann graduated from the University of Florida in 2003 with a degree in business, a minor in statistics, big plans -- and about $5,000 in credit card debt.

That debt was enough to send her back home to live with her parents for three years, during which she learned the tough financial lessons confronting many young people saddled with consumer debt and increasingly hefty student loans.

"I had a hole to dig myself out of, and therefore moving home was the only answer," said Grossmann, 25. "If I tried to pay rent, that would be just extending the amount of time it would take for me to pay off my credit card."

Such are the trade-offs facing many recent graduates. Some -- known as the Boomerang Generation because they just keep coming back -- move in with their parents, and others scrape by on their own. Either way, this is when young adults gain their financial footing by learning to juggle needs and wants. Call it Personal Finance 101, the hard way.

"Today's recent grads are dealing with more money issues ... really than any generation before them," said Todd Romer, executive director of Young Money magazine. "If they were not able to save and be frugal during college, they'll still need to attempt to be frugal in those first few years after college."

For recent graduates, trying to live within a budget is complicated by low starting salaries, minimal savings and often high educational and other debts. Student Monitor, a New Jersey research firm that specializes in the college market, puts a graduate's average student loan debt at $25,760, which will take an estimated 7.9 years to pay off.

Credit card liabilities can also weigh heavily. A recent survey of college seniors by the firm showed that though 60 percent paid their balance in full each month, those who didn't carried an average balance of $617. Other research suggests that credit cards may be an even greater burden as young adults get older: An analysis of Federal Reserve data by the policy-research group Demos: A Network for Ideas & Action showed that adults between 25 and 34 have an average credit card debt of $4,358.

Numbers like these have driven many young adults back to the nest after their college graduation. A report released last month by Experience Inc., a Boston firm that recruits at universities across the country, showed that more than half of the approximately 300 students surveyed moved in with their parents after college, with 32 percent staying more than a year. Forty-eight percent of those living at home said they did so to save money.

Financial planners say that for those who live at home, saving money should be the top priority. Shashin Shah, a financial planner with SGS Wealth Management in Texas, advises young adults living at home to sock away at least 10 percent of their salary. That should be done in part through a 401(k) if offered by their employer. Shah says recent graduates should try to save for retirement, even if that means taking longer to pay outstanding credit card balances, though other advisers say paying off those debts should come before anything else.

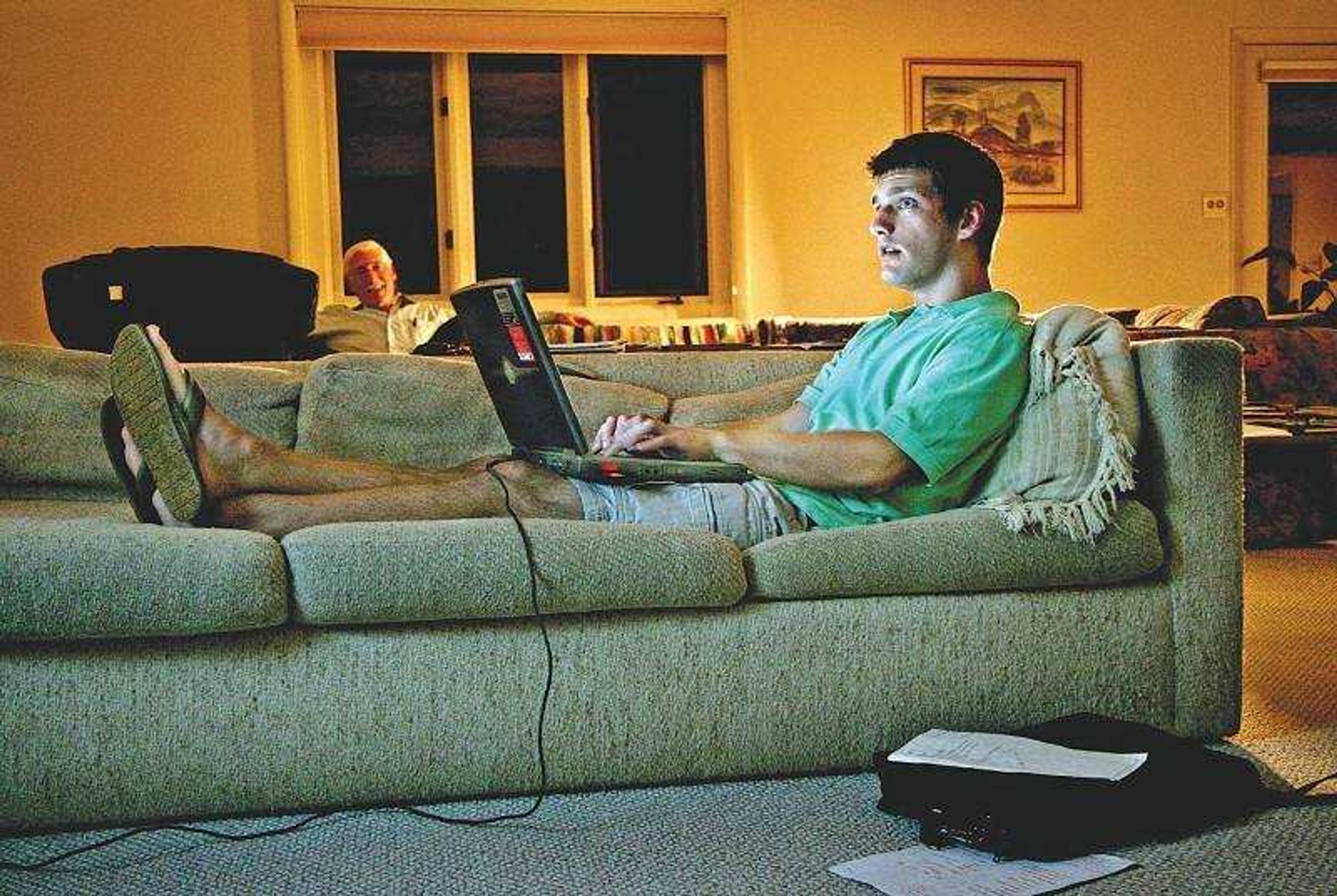

Saving for retirement has not gotten much consideration yet from Seth Niedermayer, 22, a Yale University graduate who is back at his parents' home in Bethesda, Md., after spending six weeks traveling through Europe. He plans to work for a year, either in Washington or New York, then go to law school. He anticipates his salary will be about $35,000. He had some money saved up from summer jobs, but he spent much of it in Europe.

"Preliminarily, I think what we thought was that if he's living at home, it's an opportunity for him to save his money," said Seth's mom, Gail Ross. "We would not charge him room and board, but he would be expected to help around the house."

Abby Wilner, co-author of "Quarterlife Crisis" and "The Quarterlifer's Companion," recommends that parents and their children discuss financial goals and expectations, including the length of time spent at home. Whether it's with chores or rent, parents should require that children contribute to the household.

Wilner offers a template for a "contract" between young adults and their parents that includes the amount of time per week young adults must spend researching careers and how much access parents can have to their bedrooms.

Experts (not to mention young adults and their parents) debate the merits of charging rent. Elina Furman, author of "Boomerang Nation," said rent is crucial to teach responsibility, even if it is a nominal $50.

"It's a very important gesture that implies that you're an adult and want to be treated as an adult," she said.

Furman acknowledges that some parents think asking for rent defeats the purpose -- the more money their children can sock away, the more quickly they can move out.

Furman recommended that parents who are uncomfortable taking money from their children invest those rent payments in an interest-bearing account and return it when the children move back out.

Ben Somers, 23, had to pay his parents $125 a month after he moved back into their Chevy Chase, Md., home last summer. When asked about his parents' philosophy for charging him rent, Somers was hazy.

"I don't know," he said. "Morals [are] behind it, probably." What he does know, however, is that $125 is much less than the $815 rent for the efficiency apartment he plans to move into this month. He knows he'll have less money now but hasn't started seriously thinking about a budget.

"Everybody tells you to save," Somers said. "And it's the hardest thing to do when you're living paycheck to paycheck." End optional trim Maria Varmazis, 22, knew almost immediately that she would have trouble saving after a long talk with her parents before she graduated from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in May.

Together, they wrote up a budget, including estimated rent, gas prices and insurance. Then they considered her expected salary. The financial picture was not pretty.

"We concluded that I could feasibly live on my own and have my own apartment," she said. "But I'd basically be throwing money down the drain if I'd be paying rent every single month." So Varmazis moved back into the family's home outside Boston and began work at a trade publication that pays less than $40,000 a year. She hopes to save at least that much by living at home and then use the money for a down payment on a place of her own.

Varmazis has a savings account and contributes to a Roth IRA, and she shows her parents her financial statements every month. Her bills include car insurance (less than $900 a year), gas ($1,700 a year) and cellphone service ($36 per month).

While she has budgeted only $360 per year for dinners out and entertainment, in fact, this year, she is on course to spend more than that. Varmazis has made plans to attend a wedding on the West Coast soon that "pretty much blew the budget." And when she does meet her friends for a night out in Boston, she makes sure it's worth her while.

"When I do something," she said, "I make sure it's not a little thing." - - - For young adults who decide to live on their own, financial planning experts say it is crucial to set up a budget that incorporates savings and realistically accounts for housing and other costs.

Shah said that young adults preparing to live on their own should budget a little less than 30 percent of their income for housing and that car payments should not exceed 25 percent.

To prepare for her move out, Grossmann worked as a temp making $12 per hour and then got a full-time job at an accounting firm making $40,000 per year. She paid off her credit card and reimbursed $1,700 worth of car payments her parents had made.

She recently moved out of her parents' New Jersey home and stayed on friends' couches until her Arlington, Va., apartment was available. She started working about a month ago at Wealth and Tax Advisory Services Inc. in McLean, Va., where she assists in client tax preparation. And she started keeping her budget on an Excel spreadsheet to keep track of her monthly cash flow.

"I have it open right now, which tells you how obsessed I am with keeping it up," she said.

Car payment, $285.

Car insurance, $110.

Student loan payment and cellphone bill, $65 each.

Fifteen percent of her gross salary goes into her 401(k) plan and her Roth IRA. She never wants to have credit card debt again.

Grossmann knows it will hurt to see $1,100, about one-third of her monthly salary, go toward rent and utilities rather than her retirement. And she thinks she'll only make it to one football game at the University of Florida this year. When she was living at home, she traveled back to her alma mater three times a year for football games.

But she's excited about her plans to return to school: Grossmann has been accepted to Georgetown University's certificate of financial planning program. The past three years, it seems, were just training for her future career.

"That's kind of how I realized that I was interested," she said. "I'm fascinated by my own finances."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.