Freedom looms for terrorist

NEW YORK -- In 1973, a young terrorist named Khalid Duhham Al-Jawary entered the United States and quickly began plotting an attack in New York City. He built three powerful bombs -- bombs powerful enough to kill, maim and destroy -- and put them in rental cars scattered around town, near Israeli targets...

NEW YORK -- In 1973, a young terrorist named Khalid Duhham Al-Jawary entered the United States and quickly began plotting an attack in New York City.

He built three powerful bombs -- bombs powerful enough to kill, maim and destroy -- and put them in rental cars scattered around town, near Israeli targets.

The plot failed. The explosive devices did not detonate, and Al-Jawary fled the country, escaping prosecution for nearly two decades -- until he was convicted of terrorism charges in Brooklyn and sentenced to 30 years in federal penitentiary.

But his time is up.

In less than a month, the 63-year-old Al-Jawary is expected to be released. He will likely be deported; where to is anybody's guess. He had so many aliases it's almost impossible to know what country is his true homeland.

Al-Jawary has never admitted his past or offered up tidbits in exchange for his release. Much of Al-Jawary's life remains a mystery -- even to the FBI case agent who tracked him down.

Letter bombs

But an Associated Press investigation -- based on recently declassified documents, extensive court records, CIA investigative notes and interviews with former intelligence officials -- reveals publicly for the first time Al-Jawary's deep involvement in terrorism beyond the plot that led to his conviction.

Government documents link Al-Jawary to Black September's letter-bombing campaign targeting world leaders in the 1970s and a botched terrorist attack in 1979. Former intelligence officials suspect he had a role in the bombing of a TWA flight in 1974 that killed 88 people.

"He's a very dangerous man," said Mike Finnegan, the former FBI counterterrorism agent who captured Al-Jawary. "A very bad guy."

Al-Jawary has long insisted he was framed and that the government has the wrong guy. Al-Jawary declined an interview through prison officials and has since failed to answer letters mailed to him in the last year and a half, but his former lawyer, Ron Kuby, insists he "wasn't a threat in 1991 and he's not a threat now."

Federal prosecutors didn't see it that way. They point to his trip to the United States in the 1970s as proof.

On Jan. 12, 1973, Al-Jawary flew to Boston via Montreal and then to New York City. He picked two Israeli banks on Fifth Avenue and the El-Al cargo terminal at Kennedy Airport as targets for terrorist attacks.

Al-Jawary rented three cars and assembled three bombs.

One of the bombs used a sophisticated electronic-timing device commonly referred to as an "e-cell," said Terence G. McTigue, who worked on the New York Police Department's bomb squad. It was twice as powerful as the other two bombs.

On March 4, Al-Jawary -- and possibly others -- readied the cars in anticipation of Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir's visit to the city.

But the bombs failed to explode. McTigue disarmed the e-cell bomb at JFK. It was cutting edge, the work of a professional.

Explosive link

As it turns out, Al-Jawary's car bombs and the letter explosives contained similarities that made authorities suspect they were linked.

The FBI began a large investigation. Agents lifted 60 fingerprints; they all matched Al-Jawary's. They uncovered a fake Jordanian passport behind an air conditioning duct and bomb materials from a room Al-Jawary had rented at a hotel near JFK.

Agents quickly issued an arrest warrant, but he had already left the country.

Years passed. The FBI gave up the hunt.

But their quarry resurfaced in 1979. Border police stopped Al-Jawary's car as he and another man tried to cross into Germany from Austria, according to federal court documents.

In the trunk of the car, police found 88 pounds of high explosives, electronic timing-delay devices and detonators hidden in a suitcase. They also found cash and nine passports inside a portable radio that could be used to monitor transmissions from ships, airplanes or the police.

Germany released Al-Jawary long before the FBI knew that he had been taken into custody, and he disappeared once again.

FBI agent Mike Finnegan didn't know any of this when he arrived at work one day in 1988 to find the entire case file -- many volumes and thousands of pages -- sitting on his desk with a note that said: "Find Him" -- find Al-Jawary.

It took Finnegan a year to review the entire file. He followed every lead and re-interviewed witnesses. Nothing.

In the fall of 1990, Finnegan learned Al-Jawary was residing in Cyprus, but in December Al-Jawary escaped to Iraq, after he figured out the FBI was on to him. Finnegan was furious.

Then, some luck. In January 1991, Al-Jawary left Iraq to attend a funeral in Tunisia for his good friend, Abu Iyad, the leader of Black September and Arafat deputy.

But Al-Jawary was detained in Rome after Finnegan alerted Italian authorities. Months later, Finnegan was able to bring Al-Jawary back to the U.S.

Since his arrest, Al-Jawary has asserted he wasn't in New York when the bombs were planted. The FBI had the wrong guy. The Mossad had framed him. He's not from Mosul, Iraq.

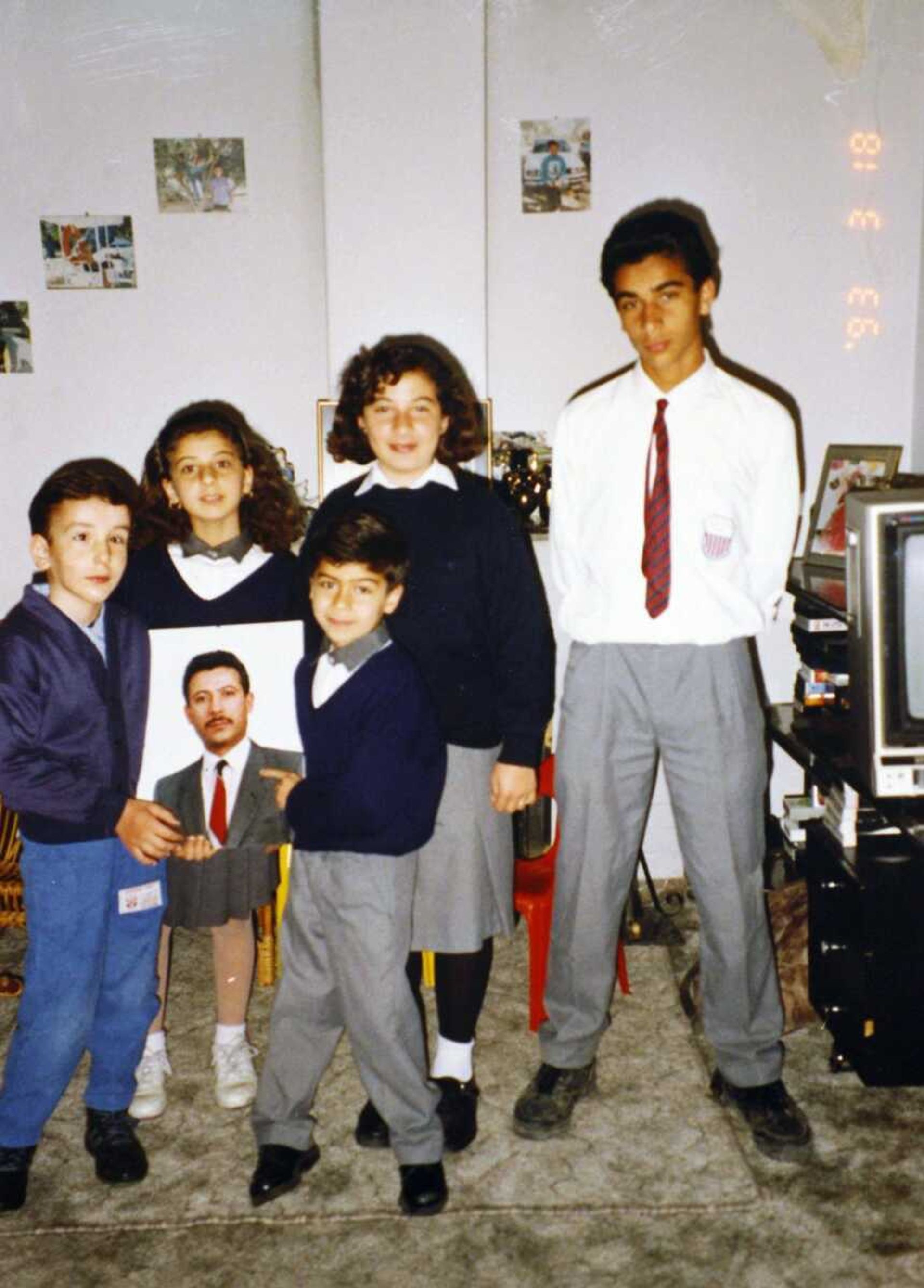

He's Khaled Mohammed El-Jassem, father of five and devoted husband, born in Palestine in 1947.

A Brooklyn jury didn't buy any of this and convicted him in about three hours.

Judge Jack B. Weinstein sentenced Al-Jawary to 30 years in prison in April 1993. In a written opinion issued after the trial, Weinstein said Al-Jawary was a serious threat.

Release in sight

"It is highly likely that were this defendant released he would continue his dangerous terrorist activities," the judge said.

Al-Jawary's appeals foundered.

But freedom looms for this gaunt and graying terrorist who was transferred recently to a federal detention center in Manhattan.

Al-Jawary is scheduled to be released Feb. 19 after completing only about half his term, which includes time served before his sentencing and credit for good behavior, according to the federal Bureau of Prisons.

Once he is released, Al-Jawary will be handed over to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and held until his deportation.

It remains unclear where he'll go, largely because Al-Jawary's true identity remains in question -- even to this day.

Those who helped put Al-Jawary behind bars believe he'll pick up where he left off.

"What is he going to do when he gets out?" McTigue said. "He'll be deported and received as a hero and go right back into his terrorist activities."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.