FDA panel backs Pfizer's low-dose COVID-19 vaccine for kids

WASHINGTON -- The U.S. moved a step closer to expanding COVID-19 vaccinations for millions more children as government advisers on Tuesday endorsed kid-size doses of Pfizer's shots for 5- to 11-year-olds. A Food and Drug Administration advisory panel voted unanimously, with one abstention, that the vaccine's benefits in preventing COVID-19 in that age group outweigh any potential risks. ...

WASHINGTON -- The U.S. moved a step closer to expanding COVID-19 vaccinations for millions more children as government advisers on Tuesday endorsed kid-size doses of Pfizer's shots for 5- to 11-year-olds.

A Food and Drug Administration advisory panel voted unanimously, with one abstention, that the vaccine's benefits in preventing COVID-19 in that age group outweigh any potential risks. That includes questions about a heart-related side effect that's been very rare in teens and young adults despite their use of a much higher vaccine dose.

While children are far less likely than older people to get severe COVID-19, ultimately many panelists decided it's important to give parents the choice to protect their youngsters -- especially those at high risk of illness or who live in places where other precautions, such as masks in schools, aren't being used.

"This is an age group that deserves and should have the same opportunity to be vaccinated as every other age," said panel member Dr. Amanda Cohn of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The FDA isn't bound by the panel's recommendation and is expected to make its own decision within days. If the FDA concurs, there's still another step: Next week, the CDC will have to decide whether to recommend the shots and which youngsters should get them.

Full-strength shots made by Pfizer and its partner BioNTech already are recommended for everyone 12 and older but pediatricians and many parents are clamoring for protection for younger children. The extra-contagious delta variant has caused an alarming rise in pediatric infections -- and families are frustrated with school quarantines and having to say no to sleepovers and other rites of childhood to keep the virus at bay.

In the 5- to 11-year-old age group, there have been more than 8,300 hospitalizations reported, about a third requiring intensive care, and nearly 100 deaths.

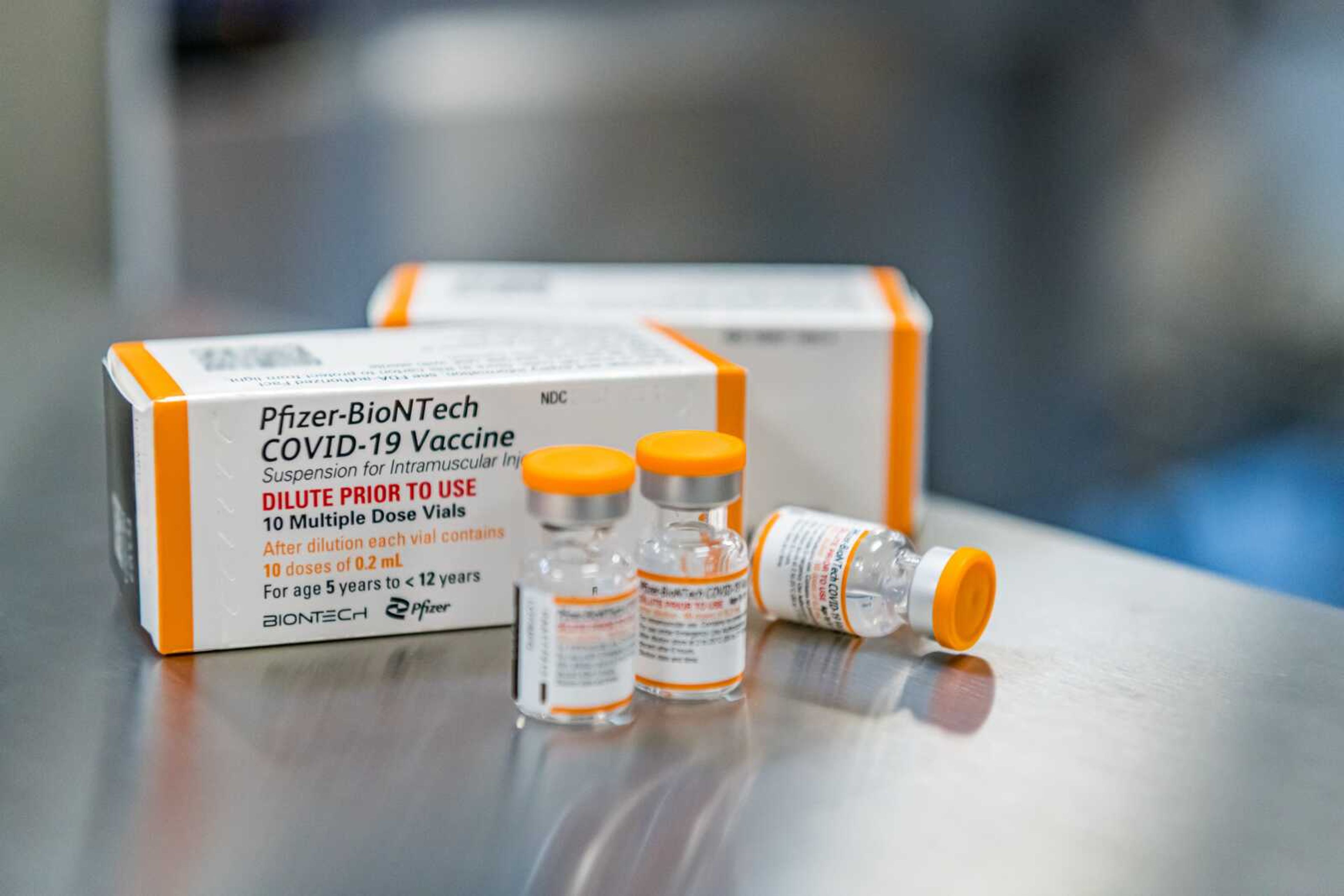

States are getting ready to roll out the shots -- just a third of the amount given to teens and adults -- that will come in special orange-capped vials to avoid dosage mix-ups. More than 25,000 pediatricians and other primary care providers have signed up so far to offer vaccination, which will also be available at pharmacies and other locations.

But for all that anticipation, there also are people who strongly oppose vaccinating younger children, and both FDA and its advisers were inundated with an email campaign seeking to block the Pfizer shot.

Dr. Jay Portnoy of Children's Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Missouri, said despite more than 4,000 emails urging him to vote against the vaccine, he was persuaded by the data showing it works. Portnoy said he also was representing "parents I see every day in the clinic who are terrified of sending their children to school. ... They need a voice also."

Panelists stressed they weren't supporting vaccine mandates for young children -- and the FDA doesn't make mandate decisions. FDA vaccine chief Dr. Peter Marks also said it would be highly unusual for other groups to mandate something that's cleared only for emergency use. Several advisers said they wished they could tailor the shots for the highest-risk youngsters, a decision that would fall to the CDC.

Dr. James Hildreth of Meharry Medical College said he ultimately voted in favor of the vaccine "to make sure that the children who really need this vaccine -- primarily Black and brown children in our country -- get it."

Pfizer studied 2,268 elementary schoolchildren given two shots three weeks apart of either a placebo or the kid dose. Vaccinated youngsters developed levels of virus-fighting antibodies just as strong as teens and young adults who got the full-strength shots. More important, the vaccine proved nearly 91% effective at preventing symptomatic infection -- based on 16 cases of COVID-19 among kids given dummy shots compared to just three who got vaccinated.

The kid dosage also proved safe, with similar or fewer temporary side effects -- such as sore arms, fever or achiness -- that teens experience. At FDA's request, Pfizer more recently enrolled another 2,300 youngsters into the study, and preliminary safety data has shown no red flags.

But that study isn't large enough to detect any extremely rare side effects, such as the heart inflammation that occasionally occurs after the second full-strength dose, mostly in young men and teen boys. The panel spent hours discussing if younger children, given a smaller dose, might face that side effect, too.

Statistical models developed by FDA scientists showed in most scenarios of the continuing pandemic, the vaccine would prevent far more COVID-19 hospitalizations in this age group than would potentially be caused by that rare heart problem.

FDA's models suggested the vaccine could prevent 200 to 250 hospitalizations for every 1 million youngsters vaccinated -- assuming virus spread remained high, something that's hard to predict. FDA scientists also said younger kids likely won't have as much risk of heart inflammation as teens but if they did, it might cause about 58 hospitalizations per million vaccinations.

"I do think it's a relatively close call," said adviser Dr. Eric Rubin of Harvard University. "It's really going to be a question of what the prevailing conditions are but we're never going to learn about how safe this vaccine is unless we start giving it."

Moderna also is studying its vaccine in young children, and Pfizer has additional studies underway in those younger than 5.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.