Demand keeps meth producers skirting the law

The first time "Bob" took methamphetamine, he was trying to increase his alcohol tolerance, he said. "I went to jail ... on a DWI, and I'm sitting in there at the Cape County pokey, and I'm talking to several inmates," he said, speaking on condition of anonymity. "I said, 'I love to drink beer, and I'm running with a couple of guys, and I always pass out, and it seems like they're going strong.'"...

The first time "Bob" took methamphetamine, he was trying to increase his alcohol tolerance, he said.

"I went to jail ... on a DWI, and I'm sitting in there at the Cape County pokey, and I'm talking to several inmates," he said, speaking on condition of anonymity. "I said, 'I love to drink beer, and I'm running with a couple of guys, and I always pass out, and it seems like they're going strong.'"

A fellow inmate recommended crank, a street name for methamphetamine.

"Everything the inmate said happened. I drank a case of beer, never got drunk. I was wide awake. I was on top of the world," Bob said.

He was hooked.

Bob eventually lost everything -- his business, his home and his family -- but nearly four years ago, he regained his sobriety.

Meth in Missouri

Bob's recovery offers a small vessel of hope amid a sea of dismal statistics that seems to be deepest in Missouri.

According to the federal Drug Enforcement Administration, Missouri led the nation in clandestine methamphetamine lab incidents last year.

The administration includes labs; dumpsites; and chemicals, glass or equipment associated with methamphetamine production in its annual count.

In 2012, DEA reported 11,210 such incidents nationwide. Of those, 1,825 -- more than 16 percent -- were uncovered in Missouri.

The good news: Efforts to disrupt the supply seem to be helping, said Cpl. Clark Parrott of the Missouri State Highway Patrol.

"From the standpoint of the sizes of the labs, I think they have shrunk. People aren't doing large production. I think it's just more of the small, single-pot method, or the 'shake and bake,'" in which producers make small amounts of the drug by shaking ingredients together in a plastic soda bottle, he said.

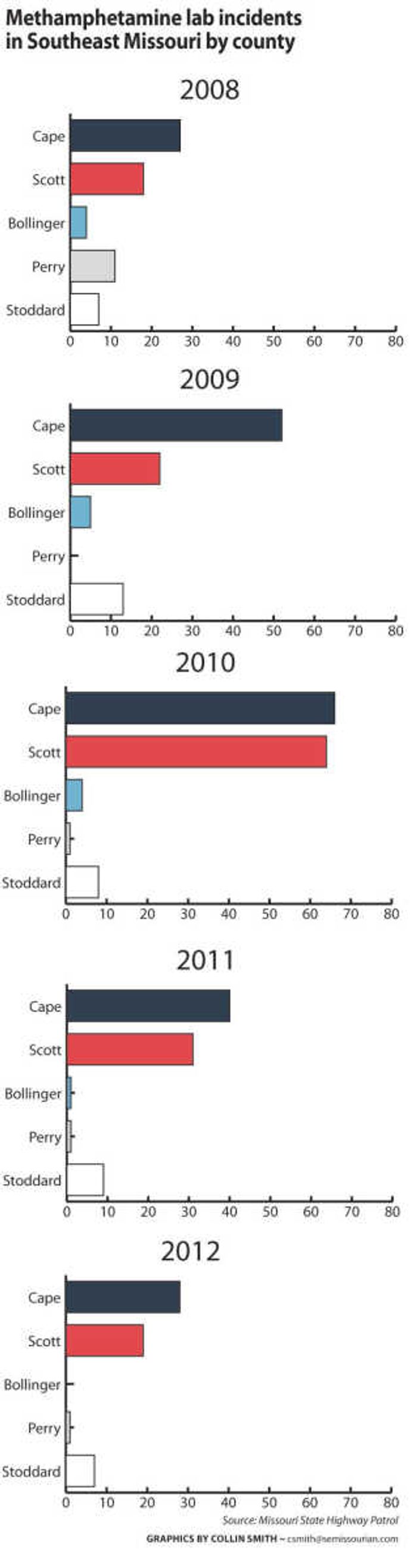

In July 2005, a state law went into effect limiting access to pseudoephedrine -- a key ingredient in methamphetamine -- and in 2010, the Cape Girardeau City Council passed an ordinance requiring the medication to be sold by prescription only. Several other municipalities have similar laws on the books.

"I think those efforts have helped," Parrott said.

Ups and downs

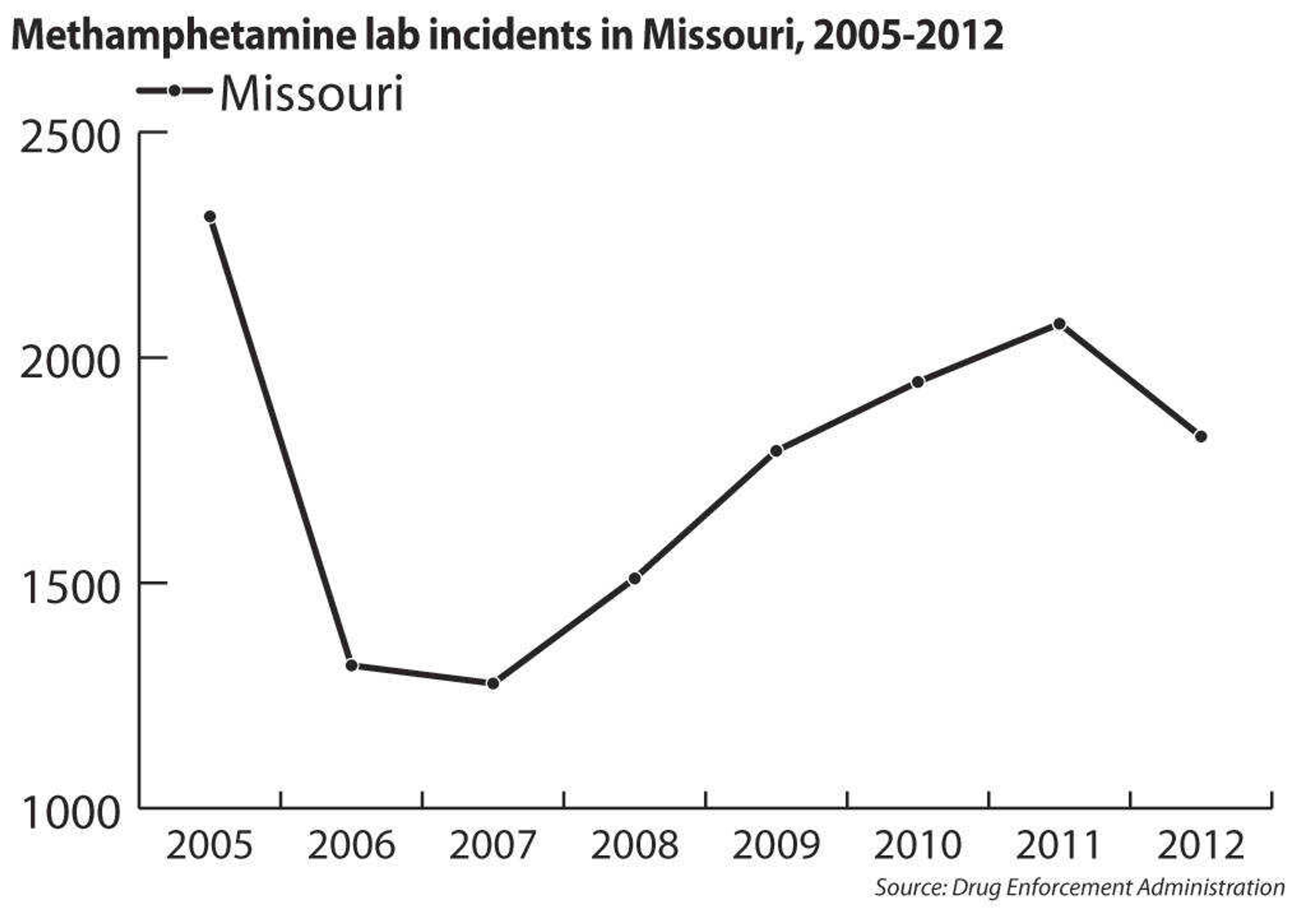

Numbers fluctuate from year to year, but the total has dropped since 2004, when Missouri had 2,913 of the 23,829 methamphetamine lab busts in the United States.

Neighboring states have seen similar patterns. In 2004, Oklahoma had 899 busts; that number decreased to 326 in 2005, after a state law went into effect, restricting consumer access to pseudoephedrine, but after dropping to 114 in 2007, the number began climbing again, reaching a high of 997 in 2011.

Missouri's biggest decrease came between 2005, when the DEA reported 2,313 labs, and 2006, when the number dropped to 1,317.

As in Oklahoma, Missouri's drop coincided with the implementation of pseudoephedrine regulations and lasted only two years.

Changes in manufacturing methods can affect the numbers, said Detective Sgt. Branden Caid of the Scott County Sheriff's Department.

New methods have made methamphetamine production less conspicuous, so in some areas, lower numbers could mean more labs are escaping detection, Caid said.

"Ten years ago, you could run around in certain neighborhoods and track the chemical smell back to the house," he said.

Today, strong-smelling chemicals such as ether or anhydrous ammonia no longer are used to manufacture the drug, Caid said.

The number of methamphetamine labs also may drop when a new law takes effect, only to rise as producers find ways around it, he said.

"I'm sure that the laws helped drastically for a time, but the people who were big into it and wanted it still found ways of getting the products they needed," Caid said.

Supply and demand

Part of the problem is the illegal methamphetamine industry -- like any other business -- is based on supply and demand, Parrott said.

"As the supply chain is interrupted, the demand is still there," he said. "I would say it's probably as high as it's been."

As long as demand for methamphetamine remains high, dealers have an incentive to supply it, Parrott said

"You won't get rid of the demand; I promise you that," said Bob, the recovering addict. "You can have the courts try to change your life around, put the pressure on you. It ain't gonna work."

The addictive nature of the chemical makes it difficult for users to give up, Parrott acknowledged.

"First time you hit it, it's just over the top, and then they start chasing that high," he said. "Your second high won't be as big as the first. Your third won't be as big as your second."

Eventually, the high is gone, but users are so dependent on the drug, they become ill without it, Parrott said.

Physical addiction isn't the only issue, Bob said.

"Mine was when I done it, I was peppy. I didn't lay around. I was always on the go. And mentally, I felt like people didn't like me without being screwed up, so what I did when I used, I'd manipulate; I'd jive talk. I felt like I fit in when I was screwed up," he said.

Related crimes

Methamphetamine presents unique dangers to law enforcement, both in its production and its effect on users, police said.

Caid said he once stopped a driver on a taillight violation, and as they talked, an unfinished batch of meth in the back of the car exploded.

"It built pressure and actually blew up in the car while I was talking to the driver," he said.

He also recalled toxic vapors literally knocking down an officer who was executing a search warrant.

"All of those secondary elements come with the meth lab that don't come with other drugs," Caid said.

Because the drug is a powerful stimulant, users may go several days without sleep, which creates its own set of hazards, Parrott said.

"We try to make a traffic stop on them, and they're so paranoid that bad things can happen," he said.

One local officer broke his thumb in a fight with an addict he was trying to arrest, and he said other addicts have shared elaborate conspiracy theories involving everything from tunnels under the city to underground helicopters.

"One thing with meth is you're real paranoid. You think people are watching you, but they're really not. You're very alert," Bob said.

Although he dismissed as bravado some users' stories of seeing monsters or other hallucinations, Bob said long periods of insomnia also can affect an addict's vision.

"Your eyes start to dilate, and you'll see dark spots," he said. "You can sit there and stare at something for the longest time, and eventually, you'll see a shadow."

Sobriety

Sometimes an arrest is the best thing that can happen to an addict, Parrott said.

That was the case for Bob, who considers his arresting officer a good friend and said he wouldn't hesitate to report another user.

"Right now, I'm not ordered to do it, but if I got a neighbor using dope you bet ... I'd snitch ... because I know what it done to me," he said.

Even after prison time and a period of sobriety, recovering addicts fight a "daily battle" to stay clean, Parrott said.

Bob uses daily prayers and meditation to put himself in the right frame of mind to deal with whatever problems arise.

"You've got to change everything about you," he said. "I've still got a lot to learn, but I'm a hell of a lot better today than I was on my best day of drinking or using."

epriddy@semissourian.com

388-3642the

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.