Dealing with discipline: School officials try to get to root of problem

Although some of the terms -- detention, in-school suspension and out-of-school suspension -- remain the same, discipline on campus has become somewhat kinder and gentler than it used to be by trying to get to the root of problems and getting children back to class...

Although some of the terms -- detention, in-school suspension and out-of-school suspension -- remain the same, discipline on campus has become somewhat kinder and gentler than it used to be by trying to get to the root of problems and getting children back to class.

Administrators say much of what they deal with are students being late to class and classroom disruptions, but there are other issues to tackle such as hormones, fights, students falling behind in their studies and mental health issues. Several officials say arriving at the source of the problem and trying to counsel students works best.

"Kids don't react to well to yelling and screaming and fire and brimstone," Scott City High School principal Mike Johnson said.

The Cape Girardeau, Jackson and Scott City districts have involved parents, students, social workers and counselors, and have added programs to help change behavior and prevent issues before they start.

Central Junior High School principal Carla Fee said social media causes many incidents at school. Decades ago, things would happen on the weekend, and it was over.

"But today, they just keep talking about it or posting, so a lot of the discipline that we deal with, at the junior high level anyway, begins on Facebook," Fee said. "Kids will come in on Monday and someone's posted a fight or pictures and made comments, and then that's what everyone's talking about, and it's a huge distraction."

Students' cellphones are supposed to be kept in their lockers, but sometimes children carry them anyway.

Next fall, Fee's seventh- and eighth-grade campus is set to receive laptop devices, just like the high school.

Superintendent Jim Welker said the computers are supposed to filter and block social media sites.

Policies, mental health

Discipline policies are spelled out in student handbooks, which vary throughout the district, Welker said. Elementary campuses may use detention during recess, while upper grades use detention during lunch, after school and Saturday, Welker said.

Expulsion is authorized by the school board if it's found the student poses a threat of harm to himself or others based on previous conduct, district policy states. In-school suspension normally lasts a few days; out-of-school suspension can go up to 10 days. If a suspension is even longer, Welker said, the principal makes that recommendation to him, and he can suspend a student for up to 180 days.

Another option, Welker said, is sending students to the Juvenile Division for five to 10 days. Juvenile officer Dr. Randall Rhodes said it provides a place for children on probation or those who have committed one too many offenses with individual attention to help them catch up with schoolwork. He said the 160 to 170 students a year come through the program.

Welker said schools send assignments to teachers at the juvenile division for students to complete.

Rhodes said counseling from New Vision Counseling also is offered, which has proved an important component.

"The idea is to send them back to school in better shape" than when they arrived, Rhodes said.

Tracking incidents

The Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education tracks discipline incidents, which are when a student is removed from a regular classroom for a half-day or more because of a violation of district, school or classroom rules, communications coordinator Sarah Potter said in an email to the Southeast Missourian. Incident figures vary each year.

"Junior high children, the closer they are together ... they're just squirrely," Fee said. " It's just the nature of their age. ... We monitor every area because they just sometimes don't always think either at that age. ... Junior high children are just different; they're just unique; there are so many changes going on."

Fee said she's noticed mental-health issues are more prevalent than even 10 years ago. Community Counseling Center has begun offering services at Central High School and some other buildings in the district.

"Part of it may be that we're identifying those issues more, too. I think the challenge sometimes in the past has been making that connection, or bridging that gap, between what we can do to help a student and having them referred to another agency. That's why we were pleased to work with the Community Counseling Center to have them bridge that gap," Welker said.

PBIS

Schools in Cape Girardeau and Jackson have used Positive Behavior Intervention System, a program that gives positive reinforcement to get students back on track -- or keep them there -- by laying out clear expectations in the classroom, on the playground or on the school bus.

Welker said PBIS is in use at Clippard, Franklin and Jefferson elementary schools and Central Middle School. Central Junior High is in its planning year for PBIS, and it's scheduled to go into effect in the fall.

Blanchard and Alma Schrader elementary schools use different character education models, Welker said. Blanchard employs the Boys Town Model, which according to its website, takes a holistic approach to children and families; Alma Schrader uses CHARACTERplus.

What the district likes about PBIS is it teaches behaviors they want students to learn. It provides interventions when there's an issue, and then teachers reteach what the students need to learn, Welker said.

"The goal there is to change behavior," Welker said, but noted this does not eliminate consequences.

Although the formal PBIS program is new to CJHS, Fee said the campus already is using its principles.

The first few days of school, Fee said, teachers talk to students about expectations. She said she tells teachers not to take bad behavior personally and to teach students about options and choices and why a particular choice might not have been the best.

"I think a lot of times ... when you explain to students this is why we have this guideline in place or this expectation, they're more receptive. But you have to spend that time at the beginning, teaching those procedures and those expectations" and following through, Fee said.

"We try to be as proactive as we can. ... We try to teach students to come to us if there are issues that they've brought from the neighborhood or something happened on the bus," she added.

Building rapport with students and treating them with respect is encouraged. Plus anytime a parent wants to see Fee or assistant principal Alan Bruns, they make time. A social worker on staff also works with families, will arrange transportation to the school for them if they don't have it, and will conduct home visits.

A proactive approach

Johnson, at Scott City High School, said he doesn't deal with a lot of discipline issues. According to Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education data, in 2013 Scott City High School had zero suspensions.

"I know other principals deal with discipline all day, every day. That's not something that takes up a lot of my time," Johnson said. Ninety-five percent of the discipline issues he handles revolve around class disruption, but tardiness also is on his radar.

"I spend more of my time counseling kids and trying to give them strategies to have a positive day," Johnson said. When students come to his office, they don't get yelling and screaming, he said.

Teachers are trained to be proactive rather than reactive.

"Almost all my teachers are tenured teachers, so they know how to take care of discipline in the classroom," Johnson said. "I have asked them in the past to handle just as much as they feel comfortable with."

Sending students to the principal's office or issuing a discipline referral is a last resort, he said.

"If I know a teacher's writing you up ... then I know that you've done something," Johnson added.

After-school detention is the main form of discipline dished out, but it's held only three days a week and typically has between two and five students.

Tardiness and classroom disruption will land a student in detention. If a student is a repeat offender, they are looking at in-school suspension.

The district's alternative school usually gets students who have fallen behind in credits. In Missouri Options, a program set forth by DESE, students can obtain a high school diploma or GED.

Getting to the cause

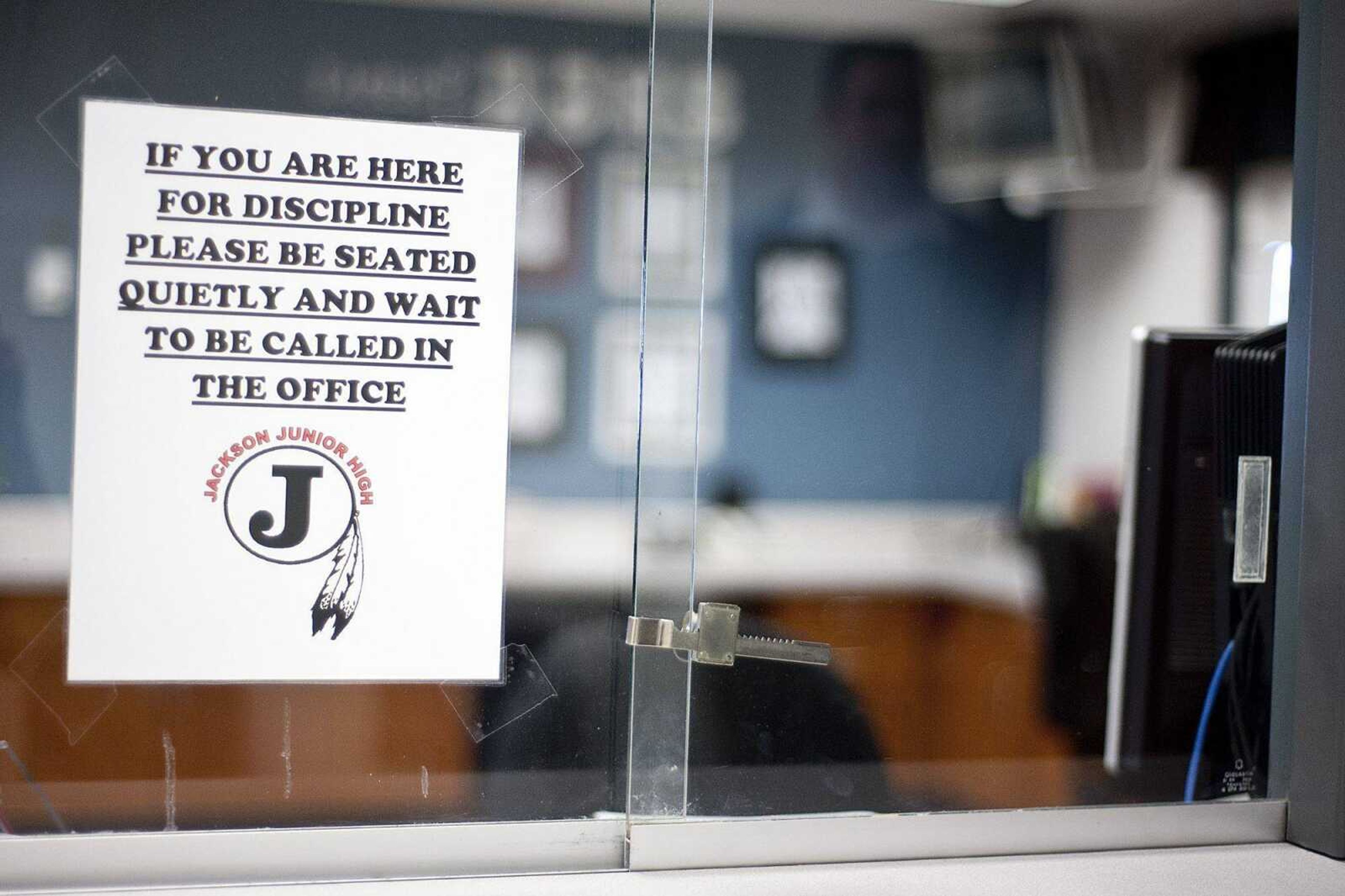

At Jackson R-2 schools, Matt Lacy, associate superintendent for curriculum, instruction and human resources, said he thinks his administrators do a good job finding the cause of why students are disruptive, absent or late to class.

"That to me is the key and it could be a wide variety of issues," Lacy said. "And sometimes it's things you wouldn't suspect. Once your figure out what's bothering that student, everybody wins."

Lacy noted Jackson has "really great parental support," and teachers and administrators "really work to communicate" with them about what's going on.

"We just try to be proactive," Lacy said.

Other things that have helped are implementation of PBIS at all Jackson elementary schools, encouraging student engagement and building relationships with students. Although PBIS doesn't extend to the upper grades, Lacy said the philosophy is used throughout the district.

But when an incident pops up, Lacy said the measures taken depend on its severity. If a student is late for class a couple of times, detention would be deemed appropriate.

"If you did something that was more serious in nature, then the discipline issue would increase through the process from [in-school suspension] to [out-of-school suspension]," he said. Frequency of the offense also would be a factor.

"Certainly you have guidelines that you follow. A lot of it depends on the situation with the student. That really comes into play with the student getting to know them [teachers or administrators] and building rapport. That's where that is really beneficial," Lacy said.

rcampbell@semissourian.com

388-3639

Pertinent address: 301 N. Clark St., Cape Girardeau

614 E. Adams St., Jackson

3000 Main, Scott City

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.