Building costs of high-tech power plant ballooning

ST. LOUIS -- The Energy Department likes the idea: Partnering with big power and coal companies to build a groundbreaking power plant in central Illinois that's virtually emissions-free, trapping greenhouse gases and storing it underground. But FutureGen's ballooning $1.8 billion cost -- largely on the backs of U.S. taxpayers -- has the government so uneasy it wants the project's consortium of corporate backers to rework the design to get the price down...

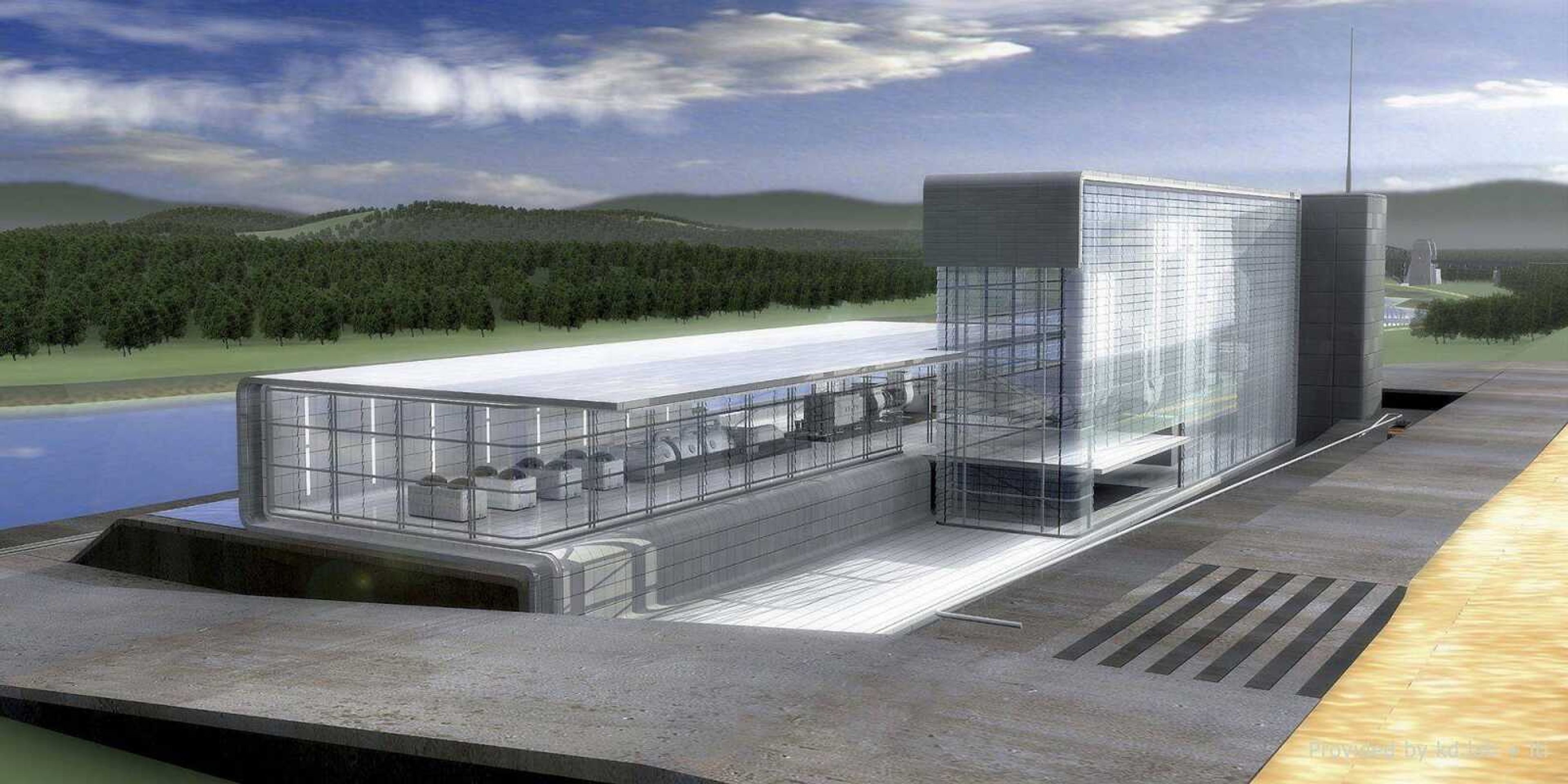

ST. LOUIS -- The Energy Department likes the idea: Partnering with big power and coal companies to build a groundbreaking power plant in central Illinois that's virtually emissions-free, trapping greenhouse gases and storing it underground.

But FutureGen's ballooning $1.8 billion cost -- largely on the backs of U.S. taxpayers -- has the government so uneasy it wants the project's consortium of corporate backers to rework the design to get the price down.

The issue has fueled a public dustup between the two sides, clouding the ambitious project's timetable at a time when construction costs -- nearly double what they'd been just a few years ago when plans for FutureGen were first laid out -- are expected to continue climbing with each day's delay.

The Energy Department -- the project's chief financier, covering three-quarters of the cost -- has held off on issuing a final stamp of approval for Mattoon, Ill., the site the corporate alliance announced with fanfare Dec. 18. Such a "record of decision" apparently is a prerequisite to the Energy Department's doling out of any of taxpayer funds for FutureGen.

The revelation that Mattoon topped Tuscola, Ill., and two Texas towns in the sweepstakes came despite the Energy Department's pleas that the consortium hold off on the announcement to give the government time to formally sign off on its earlier findings that the finalist sites are environmentally suitable.

Developers cited the interests of time and money in plowing ahead with the announcement. "Every month of delay can add $10 million to the project's cost, solely due to inflation," Michael Mudd, the alliance's chief executive, has said.

Mudd and a FutureGen Alliance spokesman did not return messages left seeking comment about the dispute with Energy Department.

The alliance's chief operating officer said last month that bids for the core technology that would turn coal to gas were to be sought beginning Jan. 2, but it's unclear if that has happened. Developers have said they need to break ground by the summer of 2009 to achieve a planned 2012 opening.

Julie Ruggiero, an Energy Department spokeswoman, declined to discuss the matter publicly and referred to letters sent last month to the alliance by James Slutz, the DOE's acting principal deputy assistant secretary.

On Dec. 18, Slutz wrote that "projected cost overruns require a reassessment of FutureGen's design," and that the Energy Department "believes that the public interest mandates that FutureGen deliver the greatest possible technological benefits in the most cost-efficient manner."

Days earlier, Slutz had questioned the timing of the site announcement, complaining in a letter to Mudd that developers were moving too fast and without consulting the Energy Department.

The Energy Department's stance isn't sitting well with Illinois' congressional delegation and Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich, who told Energy Secretary Samuel Bodman that "any delays will only drive up costs and postpone the benefits FutureGen promises to deliver."

To Ken Simonson, chief economist for the Associated General Contractors of America trade group, the spike in the project's price tag should be of little surprise, partly because potentially revolutionary projects by nature can be abstract, making cost projections difficult.

"I know it's certainly typical in many kinds of first-of-a-kind projects that lots of the costs are just a crude guess to begin with," he said. "And as they [developers] bore down on what kinds of things actually have to be done, they discover of things are costing more."

Complicating matters, he said, is that over the past four years, the costs of basic materials such as asphalt, concrete, steel and diesel fuel have risen 40 percent because of construction booms in China and torrid demand in other countries.

Any such materials "would be particularly important for this kind of project," Simonson said.

And they're not coming cheap. Simonson said diesel fuel costs over the past four years have soared by 202 percent, asphalt by 120 percent and steel-mill products by 60 percent. Other possible components, including copper, "are in fairly limited or inelastic supply," making them pricey.

"I'm hearing from government agencies at all levels -- from the Army Corps of Engineers down to local school districts -- that when they open bids for projects they had first done an estimate on three or four years ago, they're seeing huge increases certainly consistent with this 40 percent escalation," Simonson said.

Anecdotal evidence is abundant.

Across the country, plans for plants that would turn corn into the ethanol fuel additive are on hold, given soaring construction costs compounded by high corn prices that have swelled operational expenses.

In Southern Illinois, officials who in October 2001 announced plans for coal-fired, 1,600-megawatt power plant about 50 miles southeast of St. Louis estimated the project would cost $2 billion. But after years of being slowed by regulatory hurdles and environmentalists' legal challenges, the price tag swelled to $2.9 billion by the time ground finally was broken last October.

Simonson doesn't see the trend abating any time soon.

"My prediction is that for the next several years we'll be seeing construction materials costs go up an average of 6 to 8 percent each year," he said.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.