Ala. grand jury indicts trooper in 1965 killing of black man

MARION, Ala. -- A 73-year-old retired state trooper was indicted Wednesday in the 1965 shooting death of a black man -- a killing that set in motion the historic civil rights protests in Selma and led to passage of the Voting Rights Act. District Attorney Michael Jackson said a grand jury returned an indictment in the case. ...

MARION, Ala. -- A 73-year-old retired state trooper was indicted Wednesday in the 1965 shooting death of a black man -- a killing that set in motion the historic civil rights protests in Selma and led to passage of the Voting Rights Act.

District Attorney Michael Jackson said a grand jury returned an indictment in the case. He would not identify the person charged or specify the offense until the indictment is served, which could take a few days. But a lawyer for former trooper James Bonard Fowler said he had been informed that the retired lawman had been charged.

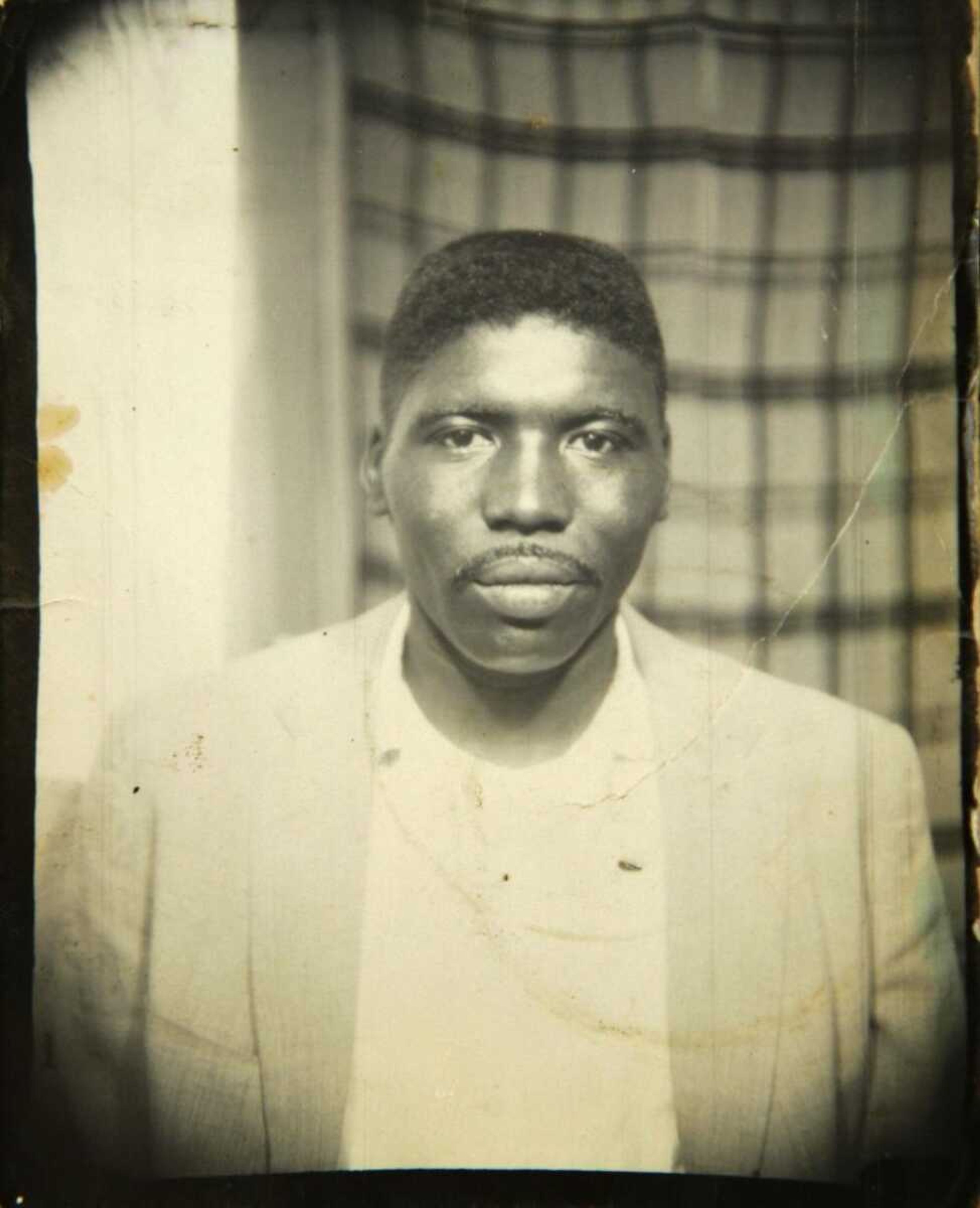

It took the grand jury only two hours to return the indictment in the slaying of 26-year-old Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was shot by Fowler during a civil-rights protest that turned into a club-swinging melee.

The case was little-known as a civil rights-era cold case but had major historical consequences.

Fowler contended he fired in self-defense after Jackson grabbed his gun from its holster. Calls to his home were not immediately returned Wednesday.

'Trying to rewrite history'

"I think somebody is trying to rewrite history, and I don't think it's fair to this trooper," said Fowler's attorney, George Beck. Beck said he was not told what Fowler had been charged with, but he said the district attorney had been talking about a murder charge, "so I assume that's what he got."

The indictment is the latest in a series of civil rights-era cases across the South that have been resurrected for prosecution after lying dormant for decades. In recent years, prosecutors have won convictions in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing that killed four black girls and in the 1964 killings of three civil rights volunteers near Philadelphia, Miss.

In light of those cases, people in Alabama began to call for a new examination of Jackson's death. Michael Jackson, who was elected in 2004 as the first black district attorney in the Selma and Marion district and is no relation to Jimmie Lee Jackson, said he acted on these calls.

Jimmie Lee Jackson's daughter, Cordelia Heard Billingsley of Marion, who was 4 at the time of the killing, said: "We'll finally know what happened. My grandchildren have asked me questions and I couldn't give them answers."

She said if not for the district attorney's election, "it would still have been swept under the rug."

Some of those who were in Marion on the night of the shooting are dead, as are two FBI agents who originally investigated Jackson's death. News reporters were also beaten and cameras destroyed during the melee, with no pictures left of what happened. The district attorney, however, said he had "strong witnesses."

Willie Martin, 74, who was at the 1965 rally that ended in violence and appeared before the grand jury, said he was glad to see action taken after 42 years. "They kept it smothered down. We didn't have nobody to represent us back then," he said.

Fowler was among a contingent of law officers sent to Marion on the night of Feb. 18, 1965. According to witnesses, about 500 people were marching from a church toward the city jail to protest the jailing of a civil rights worker when the street lights went out. Troopers contended the crowd refused orders to disperse. Soon law officers began swinging billy clubs, with marchers fleeing.

A group of protesters ran into Mack's Cafe, pursued by troopers. The cafe operator said 82-year-old Cager Lee was clubbed to the floor along with his daughter, Viola Jackson, whose son, Jimmie Lee Jackson, was shot trying to help them. He died two days later.

The shooting galvanized civil rights activists who had not been getting any national media attention in their efforts to register blacks to vote in Selma, said Taylor Branch, the Pulitzer-Prize winning author of "Parting the Waters" and other books about the civil rights movement.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. arrived to preach Jackson's funeral, and in reaction to the killing, black civil rights demonstrators set out on March 7, 1965 on a march from Selma to Montgomery. They were routed by club-swinging officers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge at Selma, an attack known as "Bloody Sunday."

National news coverage of the attack, including images of terrified marchers being beaten amid clouds of tear gas, made Selma the center of the civil rights movement. King, who was not present on Bloody Sunday, arrived to lead a weeklong Selma-to-Montgomery march later in the month.

Those events prompted Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which transformed the political makeup of the South by ending various segregationist practices that prevented blacks from voting.

The retired trooper was not asked to testify before the grand jury. All of the witnesses who appeared before the panel Wednesday are black, and none witnessed the shooting. But Vera Jenkins Booker, the night supervising nurse at the Selma hospital where Jackson died, said the patient told her what happened.

"He said, `I was trying to help my grandfather and my mother and the state trooper shot me.' He didn't give any name," Booker told reporters after her grand jury appearance.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.