$1.4 trillion in state pension fights foreshadowed in Rhode Island

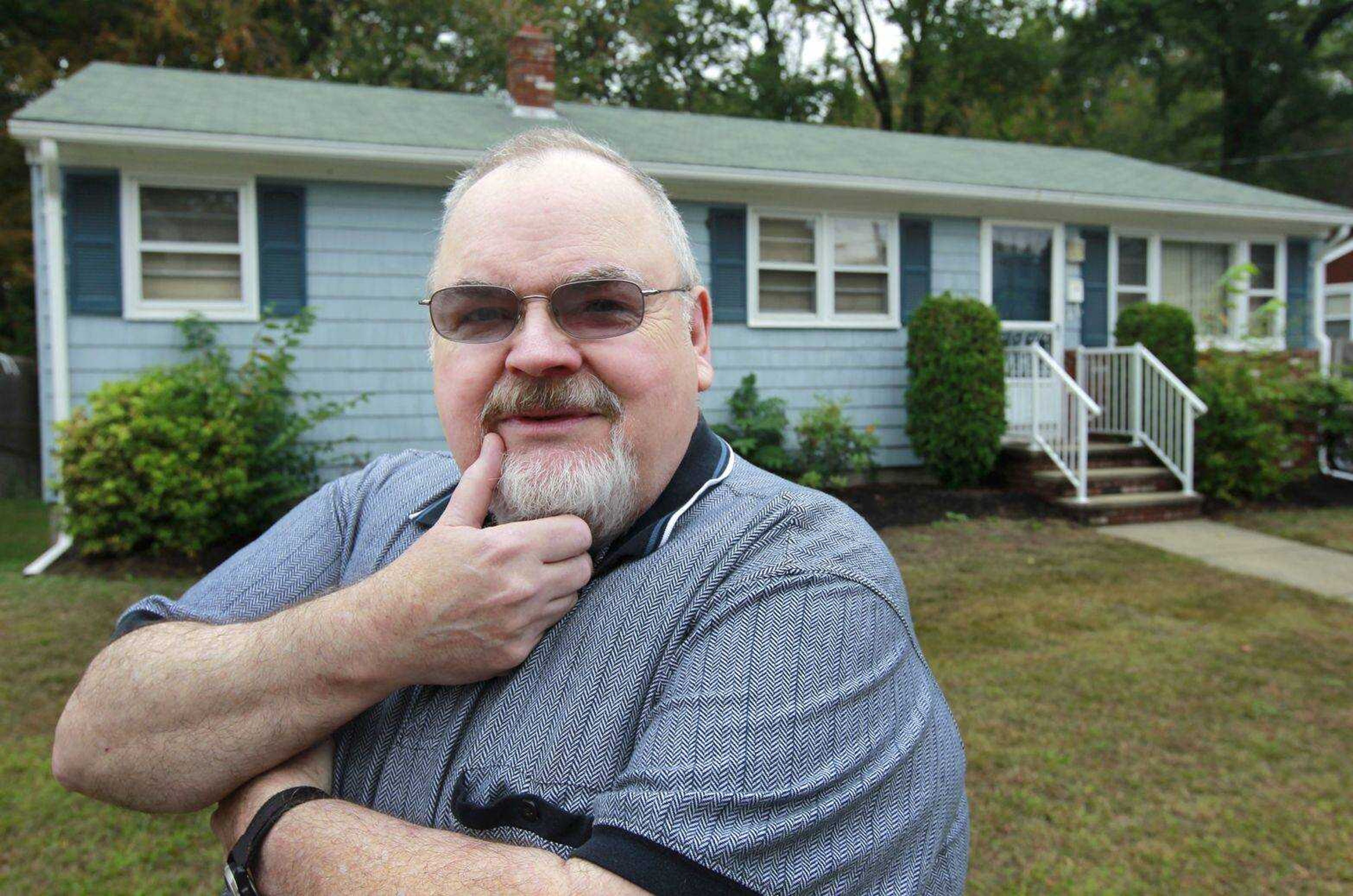

PROVIDENCE, R.I. -- Retired social worker Jim Gillis was told his $36,000 Rhode Island state pension would increase by $1,100 next year to keep up with inflation. But lawmakers suspended annual increases, leaving Gillis wondering how he'll pay medical bills and whether he'd been betrayed by his former employer...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. -- Retired social worker Jim Gillis was told his $36,000 Rhode Island state pension would increase by $1,100 next year to keep up with inflation. But lawmakers suspended annual increases, leaving Gillis wondering how he'll pay medical bills and whether he'd been betrayed by his former employer.

"When you're working, you're told you'll get certain things, and you retire believing that to be the case," Gillis said. He and other retirees are challenging the pension changes in a court battle that's likely to have national implications as other states follow Rhode Island's lead.

Cities and states around the country are shoring up battered retirement plans by reducing promised benefits to public workers and retirees. All told, states need $1.4 trillion to fulfill their pension obligations. It's a chasm that threatens to wreck government budgets and prompt tax increases or deep cuts to education and other programs.

The political and legal fights challenge the clout of public-sector unions and test the idea that while state jobs pay less than private-sector employment, they come with the guarantee of early retirement and generous benefits.

The actions taken by states vary. California limited its annual pension payouts, while Kentucky raised retirement ages and suspended pension increases. Illinois reduced benefits for new employees and cut back on automatic pension increases. New Jersey last year increased employee retirement contributions and suspended pension increases.

Nowhere have the changes been as sweeping as in Rhode Island, where public sector unions are suing to block an overhaul passed last year. The law raised retirement ages, suspended pension increases for years and created a new benefit plan that combines traditional pensions with something like a 401(k) account.

"This saved $4 billion for the people of Rhode Island over 20 years," said state Treasurer Gina Raimondo, a Democrat who crafted the overhaul. "Rhode Island is leading the way. I expect others to follow, frankly because they have to."

Public employee unions say Rhode Island is reneging on promises to workers.

"What they did was illegal," said Bob Walsh, executive director of the National Education Association Rhode Island. "We're deep into a real assault on labor. It worries me that people who purport themselves as Democrats do this."

The court case foreshadows likely battles elsewhere as states grapple with their own pension problems. In the past two years, 10 states suspended or cut retiree pension increases; 13 states now offer hybrid retirement plans that combine pensions with 401(k)-like plans.

"Forty-three states from 2009 to 2011 did something, but in many cases something was not enough," said David Draine, a researcher who tracks pension changes at the Pew Center on the States.

States are discovering the political challenge of reining in pensions is only one step in a battle ultimately won or lost in the courts.

A plan to enroll new Louisiana state workers in a 401(k)-like retirement plan is being challenged by retirees. New Hampshire is defending a law that cuts pension benefits and increases employee contributions.

California Gov. Jerry Brown last month approved higher retirement ages and contribution rates for some state workers and a $132,000 cap on annual pension payouts. The state's two main pension funds -- the California Public Employees' Retirement System and the California State Teachers' Retirement System -- are underfunded by $165 billion.

Brown said the changes may lead to bigger pension reforms in the future. Unions are ready for a fight.

"Any additional pension reform they try to do will be met with serious opposition," said Dave Low, of Californians for Retirement Security, which represents 1.5 million public workers. "Public employees have become the whipping boy."

Unions note that states have long neglected to contribute enough to pay for promised benefits. In 2010, 17 states set aside no new money for pension benefits. Kentucky hasn't made its share of pension contributions since 2004. In the past decade, Kansas and New Jersey haven't paid their full shares a single year, and Illinois has done so only once.

Steep pension fund investment losses made the situation far worse -- a federal report says state and local pension plans lost $672 billion during fiscal years 2008 and 2009.

Longer-lived retirees, higher health care bills and pension increases also drive costs. In Rhode Island, 58 percent of retired teachers and 48 percent of state retirees receive more in their pensions than in their final years of work.

Before Rhode Island's reforms passed in November, its pension costs were set to jump from $319 million in 2011 to $765 million in 2015 and $1.3 billion in 2028. The state's annual budget is $7 billion.

Passing the changes wasn't easy. Public employees rallied at the Statehouse and jeered lawmakers during floor debate. Firefighters lined the walls of committee hearings. Rep. Donna Walsh called the vote the "most heart-wrenching, gut-wrenching vote" she'd cast in 12 years as a lawmaker.

One of the biggest changes involved putting off pension increases for five years, and then only if pension investments perform well.

North Providence retiree Jamie Reilly left her job as a secretary at age 50, thinking her 30 years of state employment would mean good benefits during her later years. But now she said she may be forced to re-enter the workforce at age 55 because the state has put off pension increases.

"I counted on that money," Reilly said of the increases, which she estimates would have started at $700 to $1,000 a year. "I retired knowing I was going to get a certain amount of money. You work all your life and you plan, and they take it away from you."

Cranston firefighter Dean Brockway said higher retirement ages mean he will have to work several years longer than he expected, and he wonders how he'll climb stairs in heavy gear in his 60s. Brockway, who has nearly 30 years on the job, said reducing benefits could make it harder to recruit public safety employees.

"Could I do something else? I don't know," he said. "A lot of us chose to dedicate our lives to public service because to us it's an honor. Could I be a carpenter? I don't think so. This is what I do."

State leaders, however, said they had no choice but to reduce benefits taxpayers cannot afford. Otherwise cities might have gone bankrupt and current workers would have no retirement security, Raimondo said.

"These problems won't go away," she said. "The longer you wait, the bigger the problems get. People looking for easy, short-term solutions. ... Well, there are none."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.