History leads to next-gen aviation

An airport connects. It is where people depart for work, adventure. Where loved ones meet to say goodbye and welcome home. Where hopes and dreams are inspired by soaring jets or aerobatic twists in the sky through the wonder of flight. Cape Girardeau's airport began as a place where young men were trained as pilots for war in 1942, before there was an Air Force. It was where more than 2,500 cadets flew single prop planes, taking off and landing on Harris Army Airfield...

An airport connects. It is where people depart for work, adventure. Where loved ones meet to say goodbye and welcome home. Where hopes and dreams are inspired by soaring jets or aerobatic twists in the sky through the wonder of flight.

Cape Girardeau's airport began as a place where young men were trained as pilots for war in 1942, before there was an Air Force. It was where more than 2,500 cadets flew single prop planes, taking off and landing on Harris Army Airfield.

The flight school was managed by Oliver L. Parks, a good friend of Charles Lindbergh, who opened a group of schools in St. Louis, Cape Girardeau, and Tuscaloosa. Contracted with the U.S. government, Parks is now considered a pioneer in aviation history for flight training and aviation instruction. Parks College at Saint Louis University and Parks Field in Cahokia, Illinois, is named after him.

He was also a visionary.

In a 1944 interview with a reporter from the Southeast Missourian newspaper, Parks talked with the City of Cape Girardeau about what they could expect in the future: multiple runways with families looking to flying as they did to driving and parking cars.

"For private flying, Cape Girardeau would want two or three small landing fields, right on the edge of the residence district," Parks said in the report. "Motoring is so much a part of social and business life today that our garage is part of the home. Flying will become just as much a part of daily existence in the future. Therefore, the private flier will want his airplane hangared just across the road, if possible. In other words, we will be demanding neighborhood landing fields, small airports with turf runways."

In turn, the City bought the airfield, and local wartime pilots became its architects. One pilot, Rush H. Limbaugh Jr. who flew cargo missions over the Himalayan mountains with persecuted Chinese escaping war-torn China, worked tirelessly with local, state and federal government officials to secure funding to ensure the area had an economic hub for flight, connecting commerce with travel.

Early proponents of the airport are iconic Cape names: William Kies, John and Mark Seesing, John Godwin, James Schumacher, George Meikle, David Little, James Estes and others. For each, there are dozens of unnamed heroes of early private and commercial aviation.

More hangars, better runways, longer touchdowns and taxiways welcomed commercial transportation -- at a price.

In an era when passengers dressed up to fly, large propped DC-3 planes transported passengers daily, departures and arrivals mimicking bus schedules. There were nine-minute flights to Cairo, Illinois. Thirteen minutes to Chester, Illinois. And flights from Memphis, Tennessee, stopped in Cape Girardeau before St. Louis. In its early heyday of commercial flight, more than 10,000 passengers a year embarked on commercial planes from Cape.

And for years, things didn't change much. Aviation used the mechanics of its early predecessors: radio used for communication and triangular navigation, flaps controlled by cables and pilotage by steam gauges.

Yet, it wasn't always blue skies for the management of the Cape airport. Fires took out its first tower, barracks and hangars. They rebuilt, even though lack of funding delayed progress. An air traffic control strike in 1981 removed tower operations for years.

But with an eye on economic development, the City took over management of the tower and its costs and invested in runway expansion, often with creative solutions. Some were successful, and others were not. It became a hub for one of the largest air auctions in the United States where private planes were auctioned off, highly successful until it moved to Memphis.

More recently, city-built hangars for airplane manufacturers -- Renaissance and Commander -- resulted in undelivered and underfunded promises. And cargo flights are still elusive to what seems a smart choice for connecting sky, highway and water transport.

Still, Cape Girardeau Regional Airport continues to grow as a hub and symbol of progress. Businesses choose Southeast Missouri for its access. Procter & Gamble, Drury Southwest, Biokyowa and more all credit the airport for its access to business here and elsewhere.

In 2009, regional airline Cape Air reintroduced affordable pricing and a reliable schedule that has boosted commercial travel. This paved the way for United Airlines under SkyWest to introduce jet transportation on a 50-passenger jet with direct flights to Chicago and beyond in 2017.

Meanwhile, the tower and airfields help the crop dusters, military flights and general aviation, private and charter. More than 60 planes are hangared at the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport, with more seeking space when open.

Into the future

Under city, state and federal support -- grants and subsidies to the amount of $1 million and more -- Cape is once again looking to its future in aviation. The tangible benefits will be a new terminal designed for growth and commercial travel fueled by United Airlines and SkyWest. An outdated tower with obstructed views will be rebuilt using technology of the day ensuring the safety of flight, along with infrastructure -- runway, lights, hangars and more -- that secure Cape's place in aviation history as the hub between St. Louis and Memphis. A community that connects using highways of the sky.

Exceeding 10,000 enplanements -- or boardings -- for 2019 at the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport is big for travel and economic development in the area. It opens more than $1 million in federal funding as the airport attains "primary airport" status. Other airports in the state with this status of similar size or slightly larger include Columbia, Springfield, Jefferson City and Joplin.

The funds are targeted as part of the Airport Improvement Program (AIP), a program that provides grants to public agencies -- and in some cases, to private owners and entities -- for the planning and development of public-use airports.

This includes land, runways and taxiways, navigation aids, safety, security, snow removal, site preparation and master plan development. Not included are salaries, equipment and supplies.

---

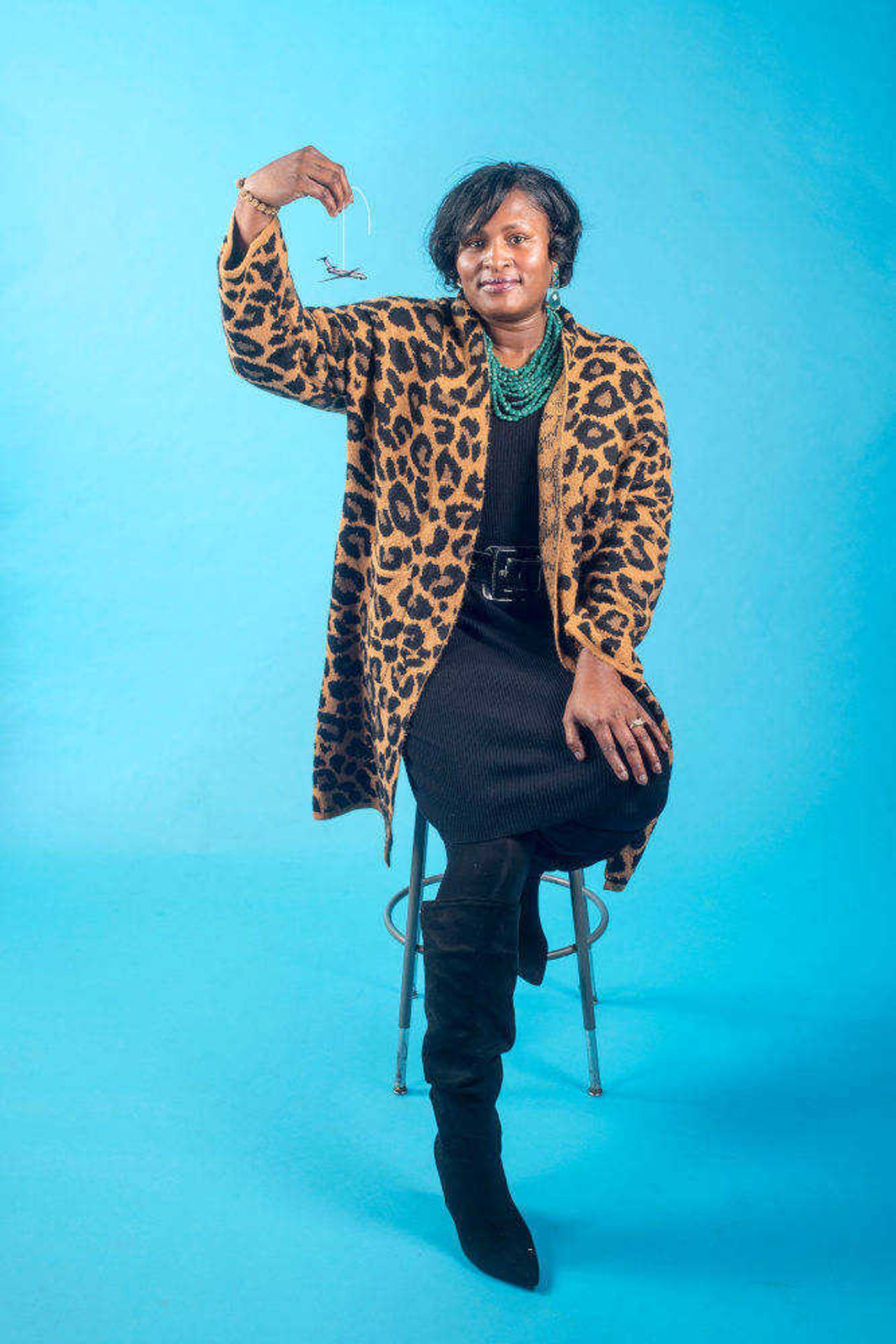

Manager: Katrina Amos

Katrina Amos, Cape Girardeau Regional Airport manager, has had her hand in most aspects of the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport throughout the past 11 years, since she first started there as administrative coordinator. She has worked closely with current airport manager Bruce Loy, playing a pivotal role in many of the airport's daily procedures and larger projects. When Loy retires Jan. 24, 2020, Amos will make her way from behind the scenes to the forefront as airport manager.

It's a career path Amos never foresaw as permanent when she began working at the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport in April 2008. In fact, throughout the years and for different reasons, she has tried to leave her post at the airport several times because she never foresaw the possibility of advancing to become the airport manager. Each time, however, with the persuasion of her team and opportunities to receive additional training and responsibilities, she has decided to stay. When she was made deputy airport manager, she says she realized this is the career path she wants to continue to pursue.

"I'm here, and I'm here to stay, and I want to see this airport grow," Amos says. "I'd like to say that at some point I had a hand in that."

Her story goes like this: with a degree in business administration and previous experience working with the City of Cape in the engineering office, Amos was hired at the airport in 2008 as administrative coordinator. It's a job she took because she wanted to work for the City again in their growth-minded culture after a brief hiatus working as a parent coordinator with a different organization. Although she says she knew "nothing" about airports, she began learning and enjoyed the atmosphere that provided her with opportunities to continue that. She became a TSA airport security coordinator, ensuring the airport was abiding by TSA regulations. This sparked her interest in the history of TSA and airports, and she began doing research to help her understand why she was doing her job.

After three years in this position, she advanced to the role of airport specialist, getting more involved in the Federal Aviation Administration's (FAA) regulations to ensure passenger safety. She also began overseeing the airport's projects, including the construction of Tee hangars, writing grants and making sure the airport followed the Missouri Department of Transportation's procedures. Around this time, she also completed wildlife hazard management training and incident management training.

Next, her title became airport operations specialist, where she says she had "a hand on some of everything," including overseeing the maintenance staff and taking a more integral role in inspections. At this time, she applied to be the airport manager of the Sikeston Memorial Airport and got the job; it was then that she realized she wanted to be an airport manager.

She told her team at the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport that she would like to train to become an airport manager. She says she had their full support, and they promoted her to deputy airport manager, the position she held directly before becoming the airport manager.

"It's just been a constant evolution, and I've been learning and learning as I go," Amos reflects.

In 2017, Amos became a certified member of the Association of Airport Executives (AAE), an achievement looked upon highly in the aviation community. The weeklong course teaches about all parts of airport operations, including finances, leasing, operations and marketing, complete with a 180-question test to demonstrate competency.

She also credits Loy, her mentor, with much of the knowledge she has amassed throughout the years.

"Bruce has always taken me under his wing," Amos says. "His retirement is kind of bittersweet for me because I have worked side by side with this man for 11 years and very closely with him the last five, and so this airport has really made huge strides, and I can see the vision he and I have talked about so long coming to fruition. And so it's always exciting to see that."

Amos is working to become a commercial drone pilot, a course which doubles as the first step in becoming a private pilot. She wants to do this to have a firsthand understanding of what pilots know about weather, the instruments used at the airport and why they do things the way they do. She says she hopes to have the title "pilot" by her name someday in the future.

Amos is looking forward to continuing helping the airport grow as manager and believes they are on "the right track" with the plan she, Loy and their team have put in place throughout the past few years.

"I'd like to see us become a multiple-destination airport at some point," Amos says. "I'd like to see us offer more corporate opportunities to business aircrafts and things like that. We're a little limited on hangar space, so that's something I'm definitely wanting to work on and see what I can do to help expand our capacity. Because right now, we are at full capacity with our hangars. ... So definitely trying to grow in terms of at least getting more airplanes based here, having more people stop here and utilize our services and what our airport has to offer. We are a neat little community, and I think our airport needs to reflect that."

It's a vision that now also has money to drive it: on November 5, 2019, the airport reached their goal of 10,000 boardings in one year, earning them primary airport status and allowing them to receive $1 million of federal funding from the FAA's Airport Improvement Program. This funding, combined with the $4.25 million capital improvement sales tax recently passed by the City of Cape Girardeau, will go toward building a new terminal and control tower at the airport as Amos and her team work on a terminal area master plan that assesses where the airport's facilities are in relation to where the airport wants to be. It will be a plan that helps the airport grow into that within the next decade, give or take.

"This is a regional airport, and we can't stress that enough. It is a huge economic tool," Amos says. "A lot of people -- a lot of businesses, especially -- if you don't have an airport where they can come in and get out quickly, they won't look at [your] community. And so we have that, and I think people need to understand that that's an important part of growth. If you want to grow, then you have to have the right tools in place, and an airport is an important tool. ... If you want to grow, that airport has to grow with you."

It's growth Amos is happy to include her team in: first and foremost, she enjoys the people she works with at the airport. In her leadership, she takes time to listen to her team members' input and ensure everyone feels included and that their voice is heard.

"I like to get everybody involved," Amos says. "When you get everybody involved and they feel invested, they have an extra interest in making sure things go well because they feel like, 'I'm a part of this.'"

She also loves that she is constantly immersed in a learning environment at the airport and that she gets to help bring celebrities and presidents to town. Watching airplanes taxiing outside her office window isn't bad, either.

In her free time, Amos says she enjoys writing short stories and is grounded in her faith. She loves to sing and directs her church's choir. And of course, she enjoys spending time with her family, including her husband of 17 years, Leroy Atkins, and their three children, Destiny, 17, Leroy Jr., 16, and Levi, 7.

Amos is looking forward to stepping into her leadership role and moving the airport forward.

"I'm passionate about the airport. I'm happy to be here. I'm excited for where we're going," Amos says. "I'm thankful for the opportunity to lead the airport, and I don't take that lightly. So everything I do, I'm always looking for 'Is this in the best interest of the community?' And just trying to make sure that I'm ordering my steps appropriately."

---

Larry Davis

Pilots and passengers rely on an airport tower for traffic control, safety and more. The controllers are unsung heroes, a voice that guides a wayward pilot home or alerts a departing pilot of an unforeseen hazard.

In Cape, the tower manager Larry Davis has operated out of the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport 50-foot tower since 1991. He has guided tens of thousands of take-offs and landings. And until this year, he did it all using technology from the tower's original build in 1975.

"People don't realize this airport is its own little world," Davis explains. "There is more activity down here, airplanes taking off and landing all day long, military arriving and departing daily. We can have 200 landings and take-offs most days."

And according to Davis, he and his controllers still rely a lot on visual spotting, but are now aided by recently-installed technology called ADSB. It's a receiver that shares aircraft location on-screen, required for any plane expectant to fly into metro airspace or class A, B and C starting in January 2020. Although this air space does not include Cape, most planes will need it, Davis says.

"With ADS-B, air traffic controllers know where everyone is," Davis says. "We can see the aircraft moving. Direction of flight. Altitude. Fly into any airport or air space around greater St. Louis, St. Charles, Creve Coeur, St. Louis downtown, you will need it."

This and GPS navigation (RNAV) are game-changers. "When I learned to fly in the '80s and you didn't have satellites or GPS, you turned knobs. It was a whole different world of navigation."

But now, according to Davis, most air traffic flies direct using GPS. Before, it was navigating by the highways in the sky -- vectors.

GPS-guided landing is also replacing most ground base omnidirectional radar (VOR), including the one (CGI) in Cape Girardeau scheduled to be decommissioned in 2020.

For Davis, all this change is seen as opportunity.

"When you plan for the future, you have to build for a good future," he says. "I don't know if you call it being optimistic. But when you undertake these projects, you build for expansion."

Whirlybird Commander: Paul Salmon

"For good or bad, we are responsible for most of the helicopters spotted above Cape," says Paul Salmon, co-owner of Cape Copters, which is located at the airport.

Holder of more than 36 world records in helicopter and gyrocopter, Salmon grew up in Cairo, Illinois, and settled in Cape Girardeau. He has been instructing helicopter and gyrocopter lessons since 2005. "We are one of the most affordable flight schools in the U.S. by design. We are as low as you can possibly get it, making our money on maintenance and selling new helicopters and gyrocopters."

Gyrocopters operate like helicopters but require a ground role of several hundred feet to take off. Then once in the air, both require active flying, "unlike an airplane that can reach altitude and trim out," Salmon says.

Salmon, with his world records, flight time as traffic helicopter pilot for Los Angeles radio KTLA (home of Ryan Seacrest) and more than 1,000 hours of instruction a year in Cape Girardeau, is well known in the gyrocopter and helicopter world. It's a growing industry that helps people learn to fly and land anywhere with permission of the land owner and airport control tower if within five miles of the airport.

This includes a growing field of agricultural flying. "The major area of expansion for us is in crop dusting," Salmon says. "It is a very precise application. We can get 18 inches to two feet off the top of the crops with very little drift."

And in the future, the smaller and lighter gyrocopters may be the closest thing to a personal aircraft parked in a garage and a local commute with a neighborhood 300-foot runway. Salmon would know.

Instructor: Bev Cleair

Beverly J. Cleair has a passion for flying that she has shared with countless students since starting her career as a flight instructor. She is recognized as one of the top flight instructors in the Midwest for sport, private, instrument and commercial flying. An early adopter of technology, she was designated by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) as one of a few instructors to take part in a special program to train Air Safety Inspectors (ASI) in St. Louis, one of three such programs in the United States.

Based with an office at the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport, Cleair instructs students of all interests in aviation, matching her teaching with their interests.

"There are two types of people learning to fly: those who wish a career in aviation, and those who want to fly for recreation," Cleair says. "It is those who want to move on that need to learn the technology, being comfortable with screens and buttons. Technology is taking over everything. Airlines train their pilots on simulators. The experience is so real."

So much so that the FAA now allows time in simulators to be counted for pilots who need to demonstrate proficiency in landing and approaches to airports in all kinds of weather, a requirement for those licensed to fly using instruments only.

According to Cleair, this enables a pilot to practice flying more, testing their skills in the worst of weather, at most any airport in the world.

"Technology is moving so quickly; we are seeing marvelous changes on all levels," says Cleair, who is also a co-owner of a business that sells and supports Remos light sport airplanes that allow training at all levels -- recreation, instrument and commercial -- requiring technology unavailable to sport airplanes until just recently.

When asked about the expected plans for the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport, Cleair says, "We need hangars badly" for private owners and businesses. "A hope shared by many."

Charter Pilot: Bill Beard

Bill Beard started Cape Air Charter in 2001. An aircraft owner and airline transport pilot for more than 35 years, Beard has logged more than 15,000 hours.

Beard spends most of his time providing charter service in his single turboprop Pilatus PC-12 and multi engine King Air 200GT and is excited about the future of aviation.

"It is a great deal safer in the air. New technology gives pilots and Air Traffic Control a lot more information. There is a better awareness of traffic in the air with heightened position and situation awareness," Beard says. "We also have real-time information in the cockpit on smart devices. iPads and smartphones give us immediate access to weather, maps, approach charts and more. This allows us to do things electronically that before required time with Air Traffic Controllers on the phone or on the radio. This includes the filing of flight plans electronically."

Beard is also happy to see more choices for newer planes, including the emergency parachute option for a Cirrus SR22 single prop plane. "A lot more non-pilots feel safer in the sky," he says.

Beard says he is also interested in the future of battery-powered airplanes with vertical takeoff ability used for short trips. According to Beard, these will be used for in-air uber-type trips.

In fact, Beard is already benefitting from uber-like trips with an online booking site for larger charter planes -- Avinode online. It's a service that shares availability of his airplanes to those seeking transportation across the United States.

"I am now flying to St. Louis, Memphis and even to Austin, Texas, to pick up passengers," he says. "My being centrally-based out of Cape with lower overhead makes this space competitive."

With all the good that is happening in aviation, Beard's main ask of the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport is help in finding more private hangar space for all those who wish to house planes, bought or leased. "We desperately need to address this need to grow our community," he says.

Chairman of the Board: Dennis Vollink

Drury Southwest leaders, engineers and architects frequently fly to locations to scope out property and manage those they own. As a vertically integrated company, Drury Southwest purchases land and buildings for hotel use and also builds and designs each property, now with properties in 21 states.

Having access to their own jet transportation -- a Citation and a newly acquired Cirrus Vision jet -- accelerates their growth.

"We are able to mobilize our forces quickly. We can take off in 10 minutes. Flying in the corporate airplane reduces days of travel time. Two hours in the air replaces two days of commercial travel and road time," says Southwest Vice President and Chairman of the Board of Drury Southwest, Dennis Vollink. "The benefits to the employees in time saved are many. Plus, a lot of the locations we travel to aren't just to the major metropolitan areas. They're in places that require multiple flights when using commercial."

Vollink credits Bob and Charles Drury for being early adopters of business aviation, witnessing firsthand how an airplane can make the difference between a successful deal and a missed opportunity. Hired in the early 1980s as Drury's pilot and engineer, Vollink has had a front-row seat to the growth of Drury development and aviation.

"We plan to keep at least two airplanes and multiple pilots," he says. "We are also building a larger hangar with the option to house a bigger jet in the future if needed. As a business, the Cape airport is critical. Beyond the convenience, it makes business sense. Price of jets have plummeted, and the technology only gets better."

Vollink points out it is unique to have two Cirrus Visions hangared at the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport, which belong to Drury and Shannon Davis. Recognized as the most delivered business jet of 2018, the Vision (with an upgrade) is also the first jet to have the purchase option of offering autonomous flight, landing itself with a push of a button.

According to Vollink, corporate flying is a definite strategic asset for the right businesss.

Next Gen flying.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.