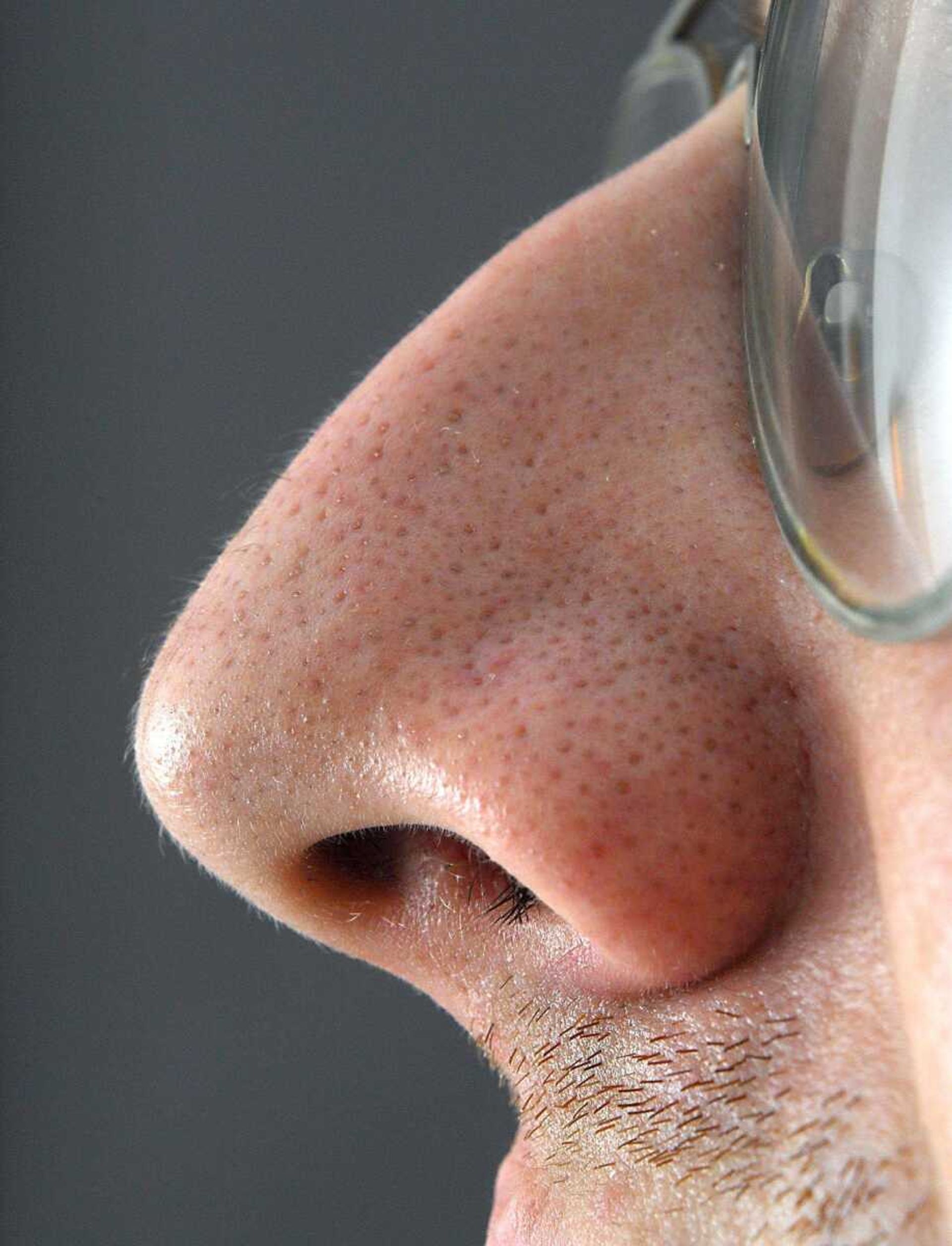

Making scents of the season

For many people, the smells of Christmas time are at least as important as the sights and sounds of the holidays. That's hardly surprising, since scientists say most people can perceive up to 10,000 odors. And genetic researchers say humans have about the same number of genes involving odor detection -- about 1,000 -- as mice. However, unlike the rodents, about half of the human genes have become inactive over the last few million years...

For many people, the smells of Christmas time are at least as important as the sights and sounds of the holidays.

That's hardly surprising, since scientists say most people can perceive up to 10,000 odors. And genetic researchers say humans have about the same number of genes involving odor detection -- about 1,000 -- as mice. However, unlike the rodents, about half of the human genes have become inactive over the last few million years.

For instance, genetic researchers at the Weizman Institute of Science in Israel recently found that volunteers who still had one particular receptor gene were much more sensitive to odors such as bananas, spearmint, eucalyptus and human sweat, while those with at least two genes with disrupting mutations were pretty much impervious to the offending odor.

Even so, there's considerable recent research that shows our noses are plenty busy, often when our mind isn't aware that a sniff test is underway.

Researchers at Northwestern University recently set up an experiment with a small group of volunteers who were asked to sniff three scents -- lemon, sweat and a neutral bottle -- with varying degrees of strength, from easily smelled to barely perceptible.

After sniffing each of the bottles, the participants were shown a picture of a face and asked to evaluate on a six-point scale, from extremely likable to extremely unlikable.

It turned out that those who were consciously aware of the different scents weren't affected by them in sizing up the images. But those who were not actively aware of the lower levels of scent were influenced in their evaluation.

"It was only when smell sneaked in without being noticed that judgments about likability were biased," said Wen Li, a

post-doctoral fellow at the Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer's disease Center at Northwestern's school of medicine and lead author of the study published in the December issue of Psychological Science.

"We may think our judgments are based only on various conscious bits of information, but our senses also may provide subliminal perceptual information that affects our behavior."

The research isn't so much about likability or marketing -- although many salespeople know that subtle scents often sell better than a whole perfume counter. What the studies are really seeking to understand is how our brains unconsciously process inputs like sights, sounds and smells and record them, often for a lifetime.

It helps to explain why many families that include a member who is memory-impaired find that the smells and tastes of the holidays may evoke strong reactions, even if they don't recall the significance.

Another study, done at the University of California-Los Angeles, used brain-imaging techniques on volunteers as they evaluated statements on various topics that were deliberately designed to be clearly true, false or undecidable.

Interestingly, the region of the brain that was most strongly activated when confronted with an obviously false statement is also known to be involved in the sensations of taste and smell, the perception of pain and feelings of disgust.

Sam Harris, lead author of the study published in the Annals of Neurology, said that suggests "false propositions might actually disgust us."

And, just perhaps, when people tell us an obvious fib and we respond by telling them "you stink" we're not just talking figuratively.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.