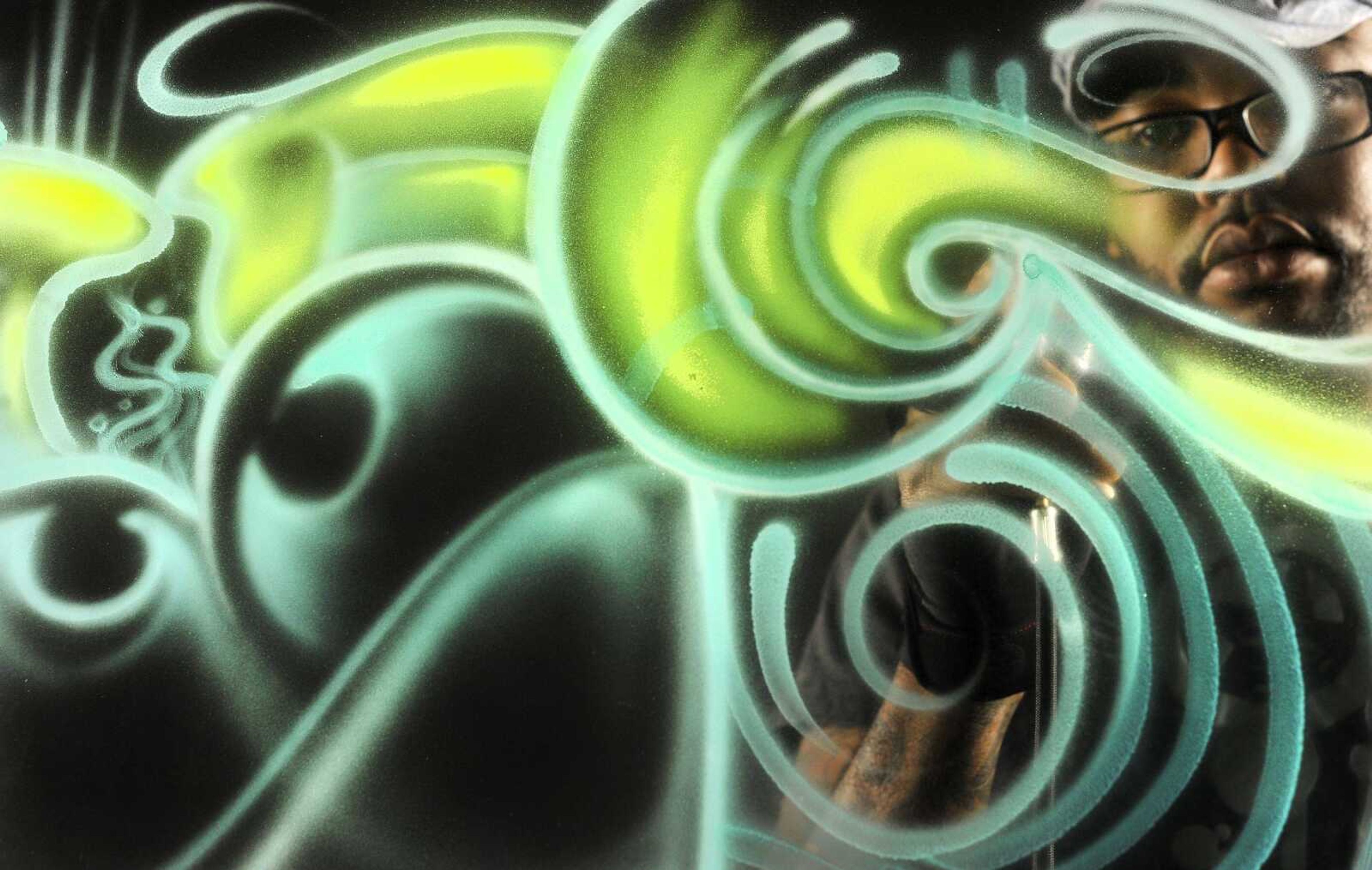

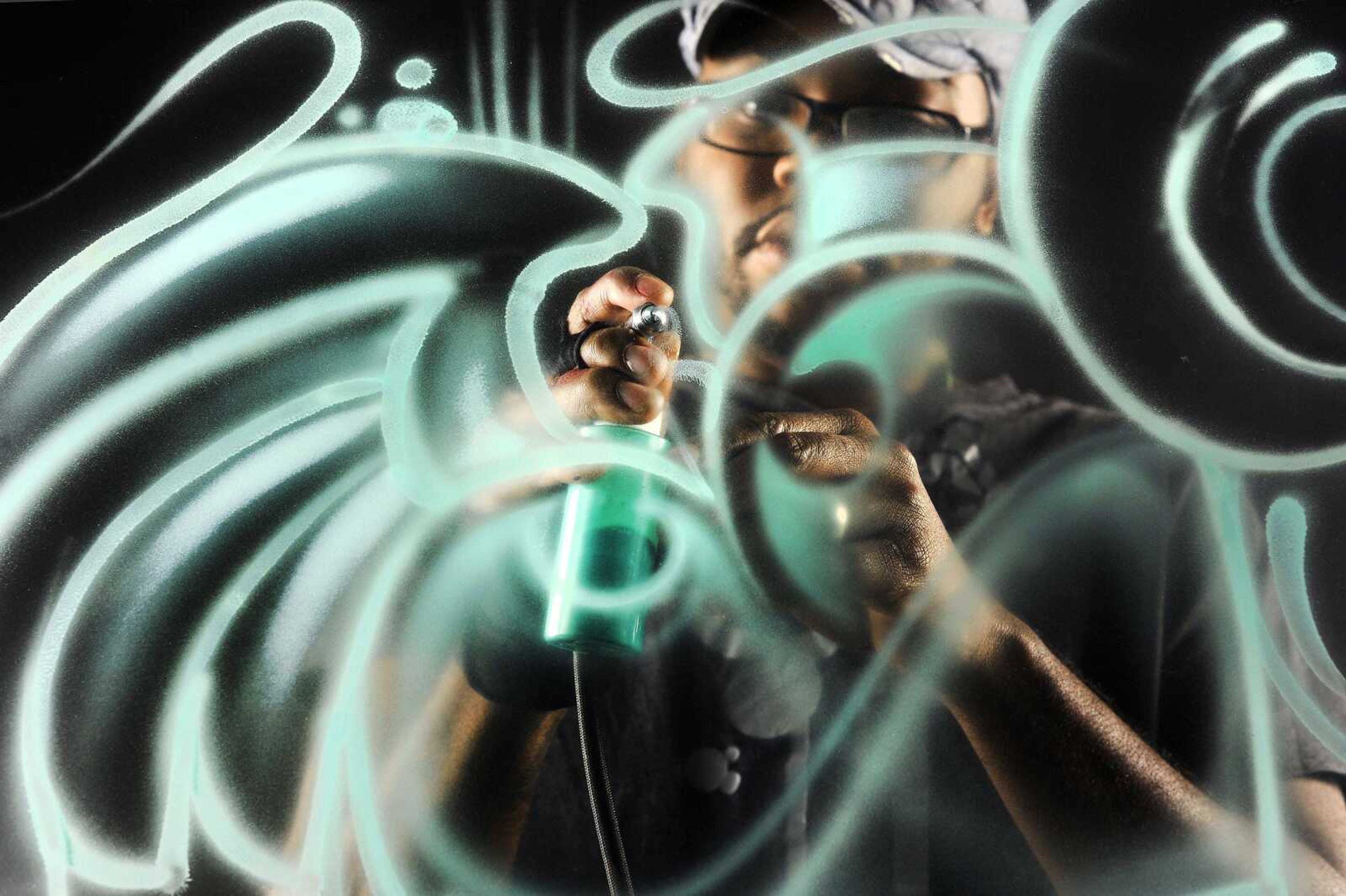

Airbrush artist brings urban influence to local art scene

Visitors to the grand opening of Malcolm McCrae's space in Bilderbach Art Plaza gaze at the airbrushed prints and canvases, taking in the colors and dreamily feathered textures. Beside the easels and artwork, there are stacks of blank hoodies, flatbill caps and T-shirts for custom work...

Visitors to the grand opening of Malcolm McCrae's space in Bilderbach Art Plaza gaze at the airbrushed prints and canvases, taking in the colors and dreamily feathered textures. Beside the easels and artwork, there are stacks of blank hoodies, flatbill caps and T-shirts for custom work.

When a boy asks how much it would cost to put his name on a hat, McCrae is patient.

"Five bucks -- how much you got?" he asks.

About a dollar and change.

"All right, hang tight little man. You hang on to that and give me a second. I'll go see if I've got a cap or something upstairs that we can do," he says.

It would go against some of McCrae's deepest convictions to deny a child access to art over money.

And McCrae was around that age himself, growing up in Columbus, Ohio, when he realized art could be not only an expressive endeavor, but a lucrative one as well.

McCrae is a hip-looking artist in his mid-30s, and his largest pieces have price tags in the thousands. But he started out piping electricity for his airbrush kit with an extension cord from a house down the block. His first setup was a custom stand in front of the house where his family was squatting at the time.

"On the first of the month, I'd use my airbrush out there," he says. "At 13, I made my first $100."

That was the moment, he says, that divides his life story -- the moment his art took him from disruptive youth to entrepreneur.

Up until that point, he says, he hadn't had a plan or vision for the future. He grew up the oldest of five kids in public housing in Milwaukee.

"My father was an art teacher with the Boys and Girls Club. Everyone would call him Mr. Baba," he says. "The art room was kind of like a safe room."

At 10, he was fascinated by street art and graffiti and found a budding sense of identity in hip-hop culture.

"I remember watching 'Yo MTV Raps,'" he says. "And there were people who looked like me. It was incredible."

When his parents divorced, McCrae's father moved to Columbus and Malcolm's emotional pain and ADHD led him to act out.

"I was the class clown," he says. "But inside, I was dealing with a lot of pain."

His mother, he says, was as supportive of his creativity as she could be, to a point. She imposed only one ground rule when it came to his painting: nothing on the walls.

"But I had my little tag, 'Chaos,'" he admits. "And I'm thinking, 'She's never going to be able to see this.'"

But his mother did find his tag on the basement wall and sent him to live with his father in Ohio.

"Columbus was a different experience," he says. "We were ... homeless. We pretty much lived in this abandoned building. It was cold, no heat or electricity, no running water. We lived there for two years."

Those two years instilled in him a resilience and a stark sense of reality, but what got him through, he says, was his art.

"I asked [my dad] you know, 'What happened?' and he said, 'This is life,'" McCrae recalls. "But he also explained that a situation doesn't make you. It's part of being successful. It's part of life ... I reflect on that as my rite of passage."

At school, McCrae built his reputation from whole cloth on the merit of his art, without the luxury of athleticism or the usual social capital. Eventually, the bullies who hassled him began hiring him.

"[One bully] looked at me and said, 'You drew this? What would you charge me to draw a card for my sister's birthday?' That kind of thing," he explains. "That became my hustle."

By his midteens, he and his father, who did screen-printing, had set up shop doing custom art.

"It was called Showtime Wild Image, and this was when I was still in high school," he says.

But the nature of the business was such that 80 to 90 percent of McCrae's clientele in the predominantly black and Latino community were ordering memorial materials. It was a bitter, heavy irony.

"It was always the same thing, R.I.P.-this, 'See you when I get there,' stuff ... We could watch the 9 o'clock news and know the next day that we would be swamped," he said. "But on the other hand, it was giving me pride putting people to work."

He recruited neighborhood kids who, like him, didn't quite fit in or needed a creative outlet.

"You can have family and a sense of community, but without a creative outlet, you're setting [a child] up for a rough life," he explains.

The man helping McCrae around his studio today was one of those kids. Eddie "Fast Eddie" Gordon was 11, a "knucklehead" in his own estimation, but into drawing. Teenage McCrae put him to work in his shop.

Now, Gordon is an artist in his own right back in Milwaukee, but says he owes a lot of his attitude and outlook to McCrae's early tutelage.

"I was just a neighborhood kid ... [Now] I'm 29, I have no criminal record, not even a traffic ticket," Gordon says. "I'll make you an outfit to go to the club, but you not gonna find me in the club ... and it's all because of art."

McCrae says mentoring is incredibly important to him.

"Young people, especially nowadays, are going through a lot," he explains. And his goal is to pass on what worked for him.

McCrae's paintings are naturally approachable for young people. It's urban, youthful folk art. He says one of the most enticing aspects of the Cape Girardeau area is the citizens' high regard for a craftsman's touch, whether it adorns a handmade broom or locally-sourced alpaca yarn, and the schoolchildren he works with are no different.

McCrae has begun working with the alternative school in town, as well as a handful of other programs, to "engage and inspire" adolescents.

"It kept me out of the streets," Gordon says. "I'd rather be in the shop than being out and end up on one of the shirts."

McCrae waves a hand around his new space, thankful for his good fortune and proud of his accomplishments, but says he's most excited about "passing it on."

"We're all gifted," McCrae explains. "My whole gift, why I'm put on this earth, is to create stuff. Ninety percent of the time, that's what I'm doing."

The other 10 percent of the time, he's focused on inspiring others.

"Do what you're put on this earth to do," he says.

tgraef@semissourian.com

(573) 388-3627

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.