Pavement Ends

James Baughn was the webmaster of seMissourian.com and its sister newspapers for 20 years. On the side, he maintained even more sites, including Bridgehunter.com, LandmarkHunter.com, TheCapeRock.com, and Humorix. Baughn passed away in 2020 while doing one of the things he loved most: hiking in Southeast Missouri. Here is an archive of his writing about hiking and nature in our area.

St. Louis versus Chicago (Part 1)

Posted Wednesday, July 20, 2011, at 5:46 PM

"The key-note of our national prosperity is sounded in the simple words, 'Cheap Transportation.' They should be stamped upon the stripes of our national banner and thrown to the breeze from every farm-house, mill, and factory throughout the commonwealth..."

-- James B. Eads, 1875

The never-ending rivalry between St. Louis and Chicago has been one of the most intense in American history. While St. Louis has long maintained the edge when it comes to National League baseball, the same can't be said about business or politics.

Since the mid-1800s, both cities have been locked in an intricate chess game, each trying to outdo the other when it comes to civic progress. Most of the moves in this game involve cheap transportation, just as important now as it was in the 1800s. For St. Louis, cheap transportation required building bridges across the Mississippi River. It was these bridges -- or rather, the lack of bridges -- that helped Chicago take the lead in this epic struggle.

Our story begins in 1820 with the establishment of the Wiggins Ferry Company, a firm that soon dominated the commercial transportation between St. Louis and Illinois. In the book Rails across the Mississippi: A History of the St. Louis Bridge, author Robert W. Jackson explains that the Illinois legislature had passed a series of bills allowing the Wiggins Company to become a monopoly.

Jackson writes, "An act pass in 1819 allowed Samual Wiggins to acquire one mile of waterfront opposite the St. Louis levee, and another act in 1829 stipulated that no competitive service could be established within two miles of the Wiggins ferry." The author adds, "A special act passed in 1853 gave the ferry company the right of perpetual succession, meaning that no other company could ever acquire the right to operate from the Illinois side of the river across from St. Louis."

What a racket. The end result of these shenanigans was that the Wiggins Company could charge exorbitant rates for the cargo transferred by their ferry boats. Without a bridge at St. Louis, shippers had no alternative. One farmer declared that the ferry company "was not only a terror, but a real vampire, sucking our very lifeblood."

While St. Louis had become the "Gateway to the West", first getting to St. Louis was a real problem. Railroad lines from the East converged on Illinoistown -- now East St. Louis -- but they had no direct connection to the Missouri railroads leading to the West.

Not that the early Missouri railroads were all that great. Despite efforts by the Missouri legislature to kickstart railroad construction by offering subsidies, these early projects were mostly busts, succumbing to financial problems, corruption, and engineering setbacks. Even when St. Louis did get a major railroad -- the Pacific Railroad connecting to Jefferson City in 1855 -- it was still a disaster.

Literally. When the inaugural train, filled with VIPs, crossed the Gasconade River, the approach to the bridge collapsed, sending the engine and all but one car crashing into the river. The calamity killed 43 people, including the president of the St. Louis city council plus several prominent businessmen, attorneys, and clergymen. The mayor, along with 69 other people, were injured.

Site of the Gasconade Bridge disaster, now marked by a modern railroad crossing.

Chicago, on the other hand, had much better success at railroad building. In the 1840s, the man who had served as Chicago's first mayor, William Butler Ogden, advocated building railroads to replace plank roads. He had trouble generating support at first, but by 1848 the city welcomed the first railroad. A couple years later, U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois was able to push through a bill to provide land grants to subsidize construction of the Illinois Central Railroad. When this railroad was completed in 1856, it was said to be the longest railroad in the world.

Historically, thanks to the Mississippi River, St. Louis merchants traded along a north-south axis. The Illinois Central, a north-south route connecting with Chicago, represented a competitive threat. Meanwhile, Chicago also boasted east-west connections via the Great Lakes and Erie Canal. The primary trade partner for St. Louis was New Orleans, while Chicago did business with a much bigger partner, New York City. As a result, capitalists on the East Coast were more inclined to invest in Chicago over St. Louis. By the outbreak of the Civil War, St. Louis had access to several hundred miles of rails, while Chicago had access to several thousand miles of rails.

In the book Yankee merchants and the making of the urban West: the rise and fall of Antebellem St. Louis, Jeffrey Adler argues that financiers from New England may have been reluctant to do business in Missouri, a slave state. Chicago, untainted by Southern sympathies, was more palatable to wealthy Yankees. Immigrants from the North may have decided to steer clear of Missouri, opting for Illinois instead. Adler contends that "the debate over the future of slavery profoundly altered the development of St. Louis and that of its principal rival."

Or maybe that explanation is too complicated. It seems hard to believe that railroad tycoons would let politics stand in the way of their financial ruthlessness. Indeed, it would have made greater financial sense to construct a railroad hub out of St. Louis, a more centrally located city, than the northern outpost of Chicago. However, the lack of a Mississippi River bridge remained a critical obstacle. Robert Silverberg writes in his book Bridges that the railroads "could not reach the Missouri city, for the Mississippi, like a giant wall of water, cut St. Louis off from the eastern half of the nation."

The issue came to a head in 1856 when the first bridge over the Mississippi River was completed at Rock Island between Illinois and Iowa. This northern route provided a convenient bypass of the expensive and unreliable ferry crossings at St. Louis. It was clear that a huge amount of cargo would now be shipped via Chicago instead of St. Louis.

Two weeks after the Rock Island bridge opened, a steamboat, the Effie Afton, crashed into a pier, causing the wooden bridge to catch on fire. The bridge was quickly repaired, but the incident led to a fight between the steamboat interests (allied with St. Louis) and the railroad interests (allied with Chicago). The pro-railroad faction accused the steamboat interests of deliberately sabotaging the bridge, while the pro-steamboat crowd accused the bridge builders of intentionally obstructing navigation on the river.

The captain of the steamboat sued the bridge company for $50,000. After some delays and posturing by both sides, the case, Hurd et al v. Railroad Bridge Company, was finally heard in Chicago on Sept. 22, 1857. The defense attorney was none other than Abraham Lincoln who made a strong case for the railroad. He argued, "One man had as good a right to cross a river as another had to sail up or down it."

The jury failed to reach a decision. In the book Bridges and Men, Joseph Gies states, "The no-verdict was a victory for the railroad and the bridge and also, interestingly enough, for Chicago over St. Louis. St. Louis was the river metropolis; Chicago was the new rail town. The Effie Afton case sharpened the bitterest rivalry between two cities in American history."

Six years later, after Lincoln became President, the Supreme Court heard the steamboat case. Gies explains, "The Supreme Court handed down an enlightened decision in favor of the defendants, finding that if the steamboat suit were granted, bridging the Mississippi could be prevented permanently."

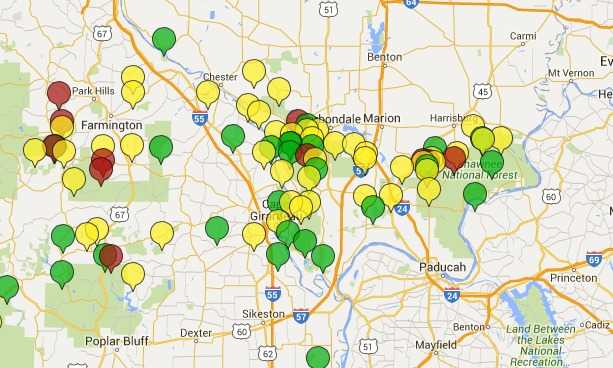

This atlas map from 1861 shows three Missouri railroads connecting to St. Louis and three Illinois railroads converging on Illinoistown (East St. Louis). The lack of a bridge is obvious. (Image from the Library of Congress)

So, at the beginning of the Civil War, Chicago had a big lead. That continued through the war as Chicago, well north of the combat, continued to grow while St. Louis found itself in the middle of the fighting. Railroad construction in Missouri was halted.

Following the war, it was clear that St. Louis needed a comeback. The city commissioned its chief engineer, Truman J. Homer, to prepare a report in 1865 on the feasibility of building a Mississippi River bridge.

Homer's rendering of a proposed bridge at St. Louis

His report stated, in grandiose fashion, "With a bridge across the river, we may safely defy all rivalry, but without it our prospects are poor indeed; and untold millions hinge upon this contingency. It is the commerce of a nation, yes, of a continent -- I might almost say, of the hemisphere."

St. Louis would build its bridge. But would it be enough to defy all rivalries?

Respond to this blog

Posting a comment requires a subscription.