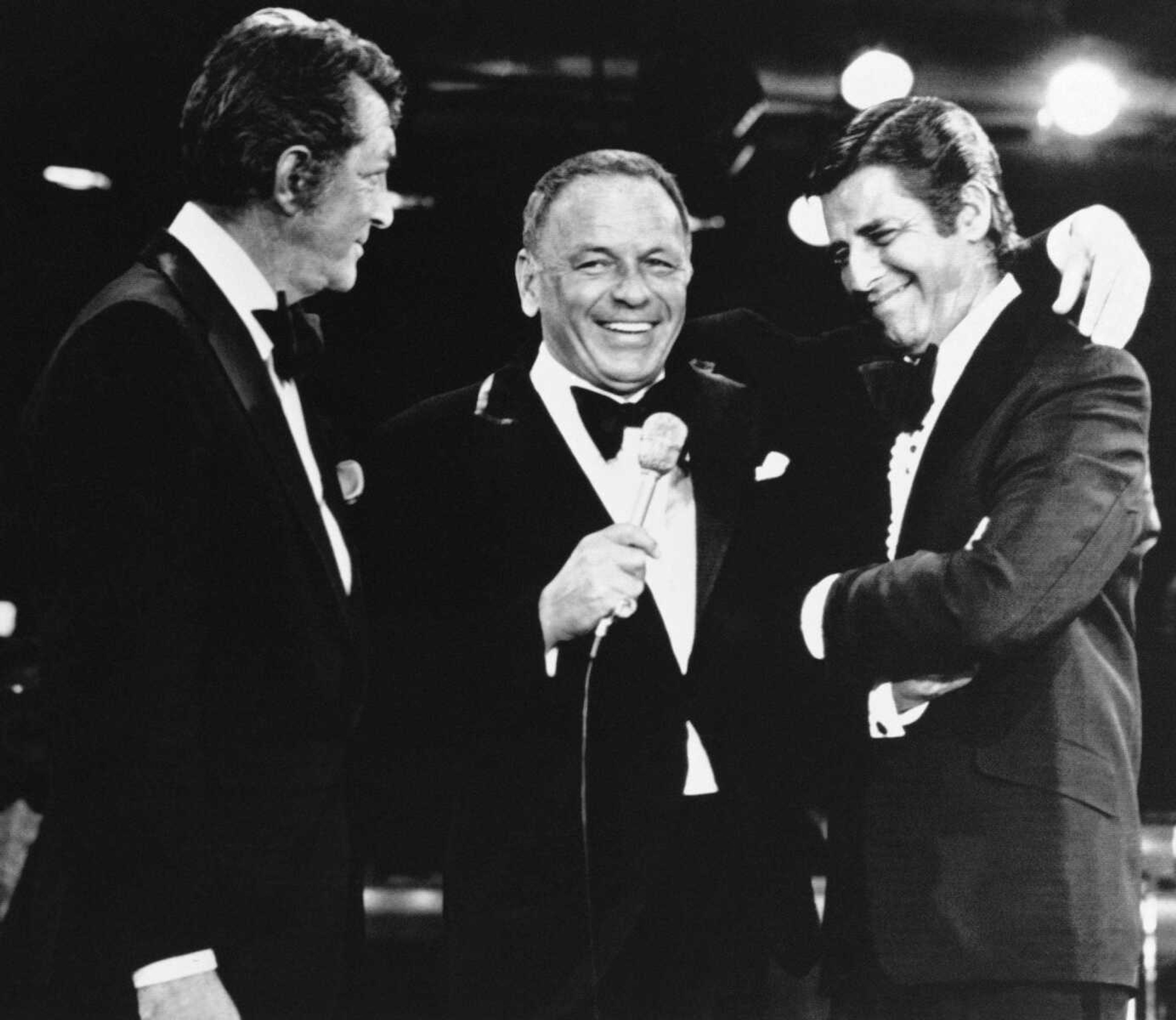

Jerry Lewis, comedian, telethon host, dies at 91

LOS ANGELES -- Jerry Lewis, the manic, rubber-faced showman who jumped and hollered to fame in a lucrative partnership with Dean Martin, settled down to become a self-conscious screen auteur and found an even greater following as the tireless, teary host of the annual muscular-dystrophy telethons, has died. He was 91...

LOS ANGELES -- Jerry Lewis, the manic, rubber-faced showman who jumped and hollered to fame in a lucrative partnership with Dean Martin, settled down to become a self-conscious screen auteur and found an even greater following as the tireless, teary host of the annual muscular-dystrophy telethons, has died. He was 91.

Publicist Candi Cazau said Lewis died of natural causes Sunday in Las Vegas with his family by his side.

Tributes from friends, co-stars and disciples poured in immediately.

"That fool was no dummy. Jerry Lewis was an undeniable genius an unfathomable blessing, comedy's absolute!" Jim Carrey wrote Sunday on Twitter. "I am because he was!"

Comedian Dane Cook considered Lewis to be a mentor.

"The world has lost a true innovator & icon," Cook wrote.

Lewis' career spanned the history of show business in the 20th century, beginning in his parents' vaudeville act at the age of 5.

He was just 20 when his pairing with Martin made them international stars.

He went on to make such favorites as "The Bellboy" and "The Nutty Professor," was featured in Martin Scorsese's "The King of Comedy" and appeared as himself in Billy Crystal's "Mr. Saturday Night."

"Jerry was a pioneer in comedy and film. And he was a friend. I was fortunate to have seen him a few times over the past couple of years. Even at 91, he didn't miss a beat. Or a punchline," Lewis' "The King of Comedy" co-star Robert De Niro said in a statement.

In the 1990s, he scored a stage comeback as the devil in the Broadway revival of "Damn Yankees."

In his 80s, he was still traveling the world, working on a stage version of "The Nutty Professor."

He was so active, he sometimes would forget the basics, such as eating, his associates would recall.

In 2012, Lewis missed an awards ceremony thrown by his beloved Friars Club because his blood sugar dropped from lack of food, and he had to spend the night in the hospital.

A major influence on Carrey and other slapstick performers, Lewis also was known as the ringmaster of the Labor Day Muscular Dystrophy Association, joking, reminiscing and introducing guests, sharing stories about ailing children and concluding with his personal anthem, the ballad "You'll Never Walk Alone."

From the 1960s onward, the telethons raised some $1.5 billion, including more than $60 million in 2009.

Lewis announced in 2011 he would step down as host but would remain chairman of the association he joined some 60 years ago.

"Though we will miss him beyond measure, we suspect that somewhere in heaven, he's already urging the angels to give 'just one dollar more for my kids,'" MDA board chairman R. Rodney Howell said Sunday.

His fundraising efforts won him the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the 2009 Oscar telecast, an honor he said "touches my heart and the very depth of my soul."

But the telethon was also criticized for being mawkish and exploitative of children, known as "Jerry's Kids."

A 1960s muscular-dystrophy poster boy, Mike Ervin, later made a documentary called "The Kids Are All Alright," in which he alleged Lewis and the Muscular Dystrophy Association had treated him and others as objects of pity rather than real people.

"He and his telethon symbolize an antiquated and destructive 1950s charity mentality," Ervin wrote in 2009.

Responded Lewis: "You don't want to be pitied because you're a cripple in a wheelchair, stay in your house!"

He was the classic funnyman who longed to play "Hamlet," crying as hard as he laughed.

He sassed and snarled at critics and interviewers who displeased him.

He pontificated on talk shows, lectured to college students and compiled his thoughts in the 1971 book "The Total Film-Maker."

"I believe, in my own way, that I say something on film. I'm getting to those who probably don't have the mentality to understand what ... 'A Man for All Seasons' is all about, plus many who did understand it," he wrote. "I am not ashamed or embarrassed at how seemingly trite or saccharine something in my films will sound. I really do make films for my great-great-grandchildren and not for my fellows at the Screen Directors Guild or for the critics."

In his early movies, he played the kind of fellows who would have had no idea what the elder Lewis was talking about: loose-limbed, buck-toothed, overgrown adolescents, trouble-prone and inclined to wail when beset by enemies.

American critics recognized the comedian's popular appeal but not his aspirations to higher art; the French did. Writing in Paris' Le Monde newspaper, Jacques Siclier praised Lewis' "apish allure, his conduct of a child, his grimaces, his contortions, his maladjustment to the world, his morbid fear of women, his way of disturbing order everywhere he appeared."

The late Associated Press writer Bob Thomas in Los Angeles and AP National Writer Hillel Italie in New York contributed to this report.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.