Author explains his novel choices

Author Kevin Brockmeier allows his imagination to wander. He examines and develops fleeting ideas to fill the pages of a novel or a chapter in a short story collection. One character in a short story works as a window washer and writes messages on the windows he cleans. Another is a mute who gives people singing parakeets.

Author Kevin Brockmeier allows his imagination to wander. He examines and develops fleeting ideas to fill the pages of a novel or a chapter in a short story collection. One character in a short story works as a window washer and writes messages on the windows he cleans. Another is a mute who gives people singing parakeets.

"Every story is different, of course," Brockmeier said in an email interview. In the case of the window washer and the mute, "they each began with an image that seemed to arrive with a shiver of meaning and that I believed carried some symbolic and emotional freight: a man whose name was spelled across his chest in light and a speechless man whose birds sang the story of his life."

Granta magazine called him one of the best young American novelists. His short stories have appeared in The New Yorker, The Oxford American and the O. Henry Prize Stories. Brockmeier will share his experiences, methods and advice with the public in a free presentation on his work at 7 p.m. Tuesday in the Glenn Auditorium in Dempster Hall at Southeast Missouri State University organized by the University Press, Journey and the College of Liberal Arts. Brockmeier will sign books following his speech.

SE Live: You were born and raised in Little Rock, Ark., and currently live there. What's the literary community like in Little Rock?

Kevin Brockmeier: It's an unusual place to be an author -- which is to say a writer as a public figure -- because there aren't many other people publishing books here. But it's a great place to be a writer for the same reason. Little Rock isn't a beehive of literary activity, which makes it easier to hole yourself away reading and writing.

SEL: Some critics have called your novels magic realism and others, fantasy or speculative fiction. How would you describe your novels?

KB: I think of myself as aspiring to work within the very particular tradition of writers whose books I happen to love. Many of those writers are realists, many others are fantasists, but all of them are authors of vision, craft and a complex and absorbing sense of what it means to be alive.

SEL: How do you negotiate the real and the fantastic elements in your stories?

KB: Largely by failing to recognize the difference between them.

SEL: What books are you reading now or have you recently read that impressed you?

KB: The five best books I've read this year are "Blue Has No South" by Alex Epstein, "A Sorrow Beyond Dreams" by Peter Handke, "Childhood's End" by Arthur C. Clarke, "The Complete Tales of Lucy Gold" by Kate Bern-heimer, and "The Other City" by Michal Ajvaz.

SEL: Where is your favorite personal writing space? What is with you in that space?

KB: I write at home, always, at a desk in the large room I've converted into my library. On that desk are the two volumes of the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, a thesaurus, a lamp, a clock, a note card with, currently, a James Salter quotation on it and my computer. Above it is a framed print of Arcimboldo's "The Librarian."

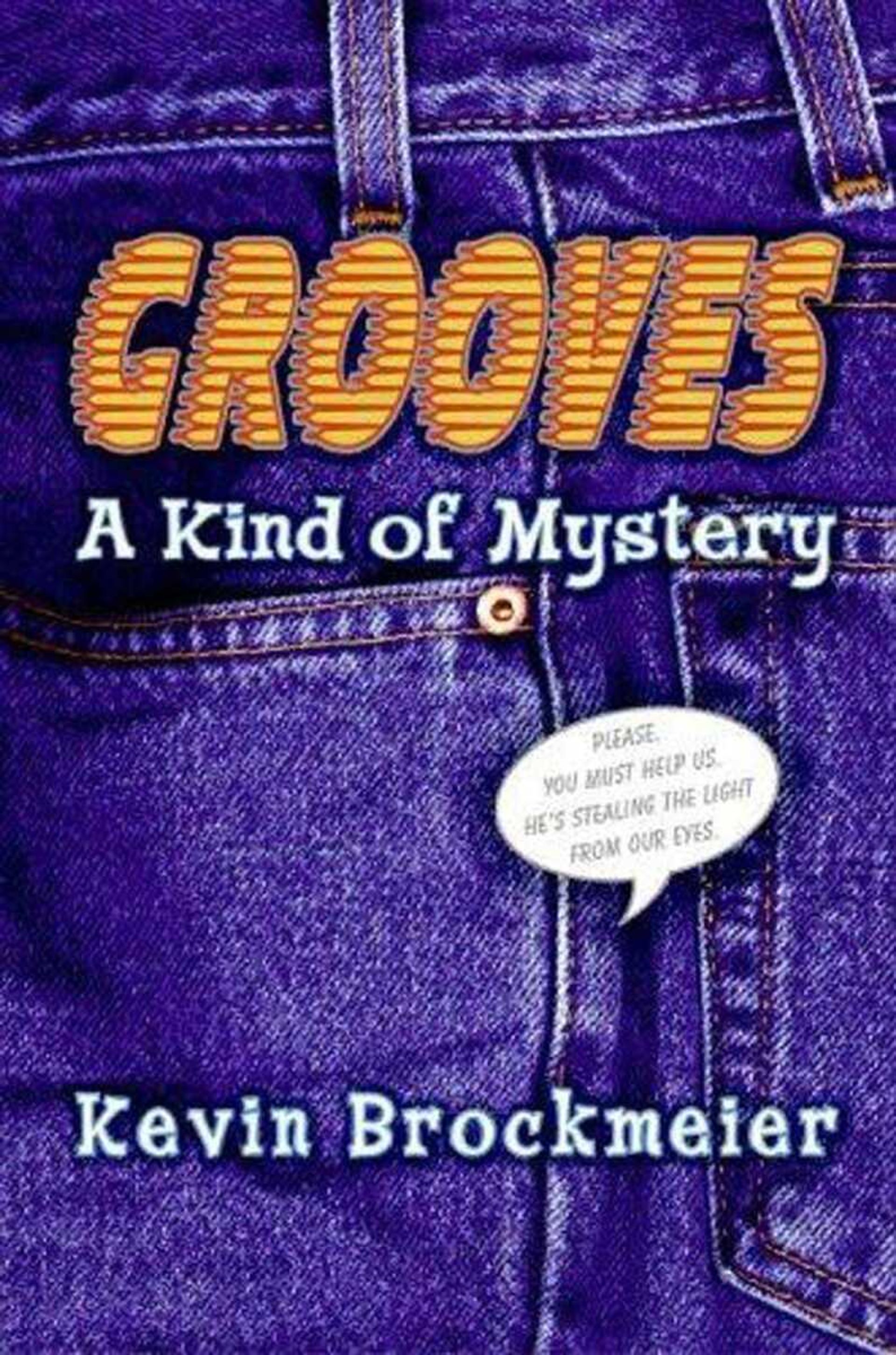

SEL: Besides your short-story collections and novels, you've also published two children's books, "Grooves" and "City of Names." Were they written for children you know, and what are they about?

KB: "City of Names" is about a boy named Howie Quackenbush who acquires a book called "The Secret Guide to North Mellwood," which teaches him how to teleport around his hometown. "Grooves" is about a boy named Dwayne Ruggles who discovers an audio message recorded in the grooves of his bluejeans: "Please. You must help us. He's stealing the light from our eyes." They were both written in part out of my own love for children's literature, but also, yes, for a particular group of kids: some daycare students who were in my charge when I was in college.

SEL: For your own writing process, how is writing for children different from writing an adult novel?

KB: I've found that my children's books are more conversational in tone than my adult books, and a lot more jokey. I want them to read as though you're listening to a child who's simply telling you his story as it occurs to him, along with anything else that happens to cross his mind. Also, it's my notion that most narratives move forward in one of two ways: either sentence by sentence or paragraph by paragraph. In my adult fiction, the unit of meaning I tend to rely on is the sentence, whereas in my children's fiction it's the paragraph.

SEL: In "The Brief History of the Dead," you create a middle world between earthly life and final death in which people who die populate a parallel earth as long as some individual who is alive still remembers them. What gave you the idea for this structure?

KB: The idea announced itself to me when I read a book by James Loewen called "Lies My Teacher Told Me," which is a work of sociology about how poorly history is taught in American high schools. Late in his book, Mr. Loewen mentions in passing a certain notion from African folklore, which served as the seed (and also the epigraph) for "The Brief History of the Dead" -- that there are three terrains of existence: the living, the dead who have not yet slipped out of living memory, and the dead who have been forgotten. I was interested in what it would be like to occupy that middle landscape, of the dead-but-not-yet-forgotten.

SEL: Why did you decide to use Coca-Cola as the vehicle for contamination in this fictional world?

KB: I wanted to find a vector of distribution for the virus that seemed both unique and plausible to me. It struck me that the world's most widely distributed consumer product might be the ideal solution.

SEL: Your character Laura Byrd may be the last living person on Earth, certainly she is the last one the narration follows. Why did you choose her for this tragic honor?

KB: I needed to find a way of isolating someone from the effects of the virus, and the Antarctic seemed the ideal place to do it. I also needed to find a vector for disseminating the virus, and Coca-Cola seemed a plausible candidate. Laura came to life at the conjunction of these two ideas.

SEL: Any rumblings that "The Brief History of the Dead" might be made into a film?

KB: Once upon a time, Warner Brothers Studios and the director Chris Columbus purchased an option on the novel, but they allowed it to lapse. The brothers Andrew and Alex Smith spent a while transforming the story into a screenplay they hoped to direct, but they never landed the financing they needed. Currently the rights are in my hands, though my agent tells me that she still receives occasional queries about the book.

SEL: Tell us about the premise of your recently released novel, "The Illumination."

KB: I was thinking about the various forms of pain people are forced to endure, wondering, really, what could all that suffering possibly be good for, and found myself conducting a thought experiment: What if our pain was what made us beautiful to God? What if our pain was the most beautiful thing about us?

I had an image of someone literally glowing with his injuries. This simple equation, of pain with light, gave birth to the book, which is set in a world that resembles our own in every way but one, namely that people's pain has begun to shed light, so that you can see -- actually see -- when somebody else is suffering.

SEL: What are you working on now?

KB: I can tell you that I'm working on another book, but I don't want to say too much about it for fear that the threads will come loose. The title is "Seventh Grade," and you can read the first section of it in the current "Education Issue" of The Oxford American.

charris@semissourian.com

388-3641

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.