Alda wants scientists to cut jargon

STONY BROOK, N.Y. -- Among the procedures Army surgeon Hawkeye Pierce performed on "M.A.S.H." was an end-to-end anastomosis. Most of the viewers, actor Alan Alda concedes, had no idea he was talking about removing a damaged piece of intestine and reconnecting the healthy pieces...

STONY BROOK, N.Y. -- Among the procedures Army surgeon Hawkeye Pierce performed on "M.A.S.H." was an end-to-end anastomosis.

Most of the viewers, actor Alan Alda concedes, had no idea he was talking about removing a damaged piece of intestine and reconnecting the healthy pieces.

Today, the award-winning film and television star is on a mission to teach physicians, physicists and scientists of all types to ditch the jargon and get their points across in clear, simple language.

The former host of the long-running PBS series "Scientific American Frontiers" is a founder and visiting professor of journalism at the Stony Brook University Center for Communicating Science, which has just been named in his honor.

"There's no reason for the jargon when you're trying to communicate the essence of the science to the public because you're talking what amounts to gibberish to them," Alda said.

A better understanding of science, Alda said, can benefit society in ways great and small. Physicians can more clearly explain treatments to patients, consumers can decipher what chemicals may be in their food and lawmakers can make better decisions on funding scientific research.

"They're not going to ask the right questions if science doesn't explain to them what's going on in the most honest and objective way," said Alda, 77. "You can't blame them for not knowing the jargon -- it's not their job. Why would anybody put up money for something they don't understand?"

Alda, who lives in New York City and has a home on eastern Long Island, said as his 12-year tenure as host of "Scientific American Frontiers" was ending in 2005, he began seeking out a university interested in his idea for a center for communicating science. He described himself as a "Johnny Appleseed" going from university to university shopping his idea.

Stony Brook, a 24,000-student state university about 70 miles east of Manhattan, "was the only place that understood what I was trying to say and thought it was possible," he said.

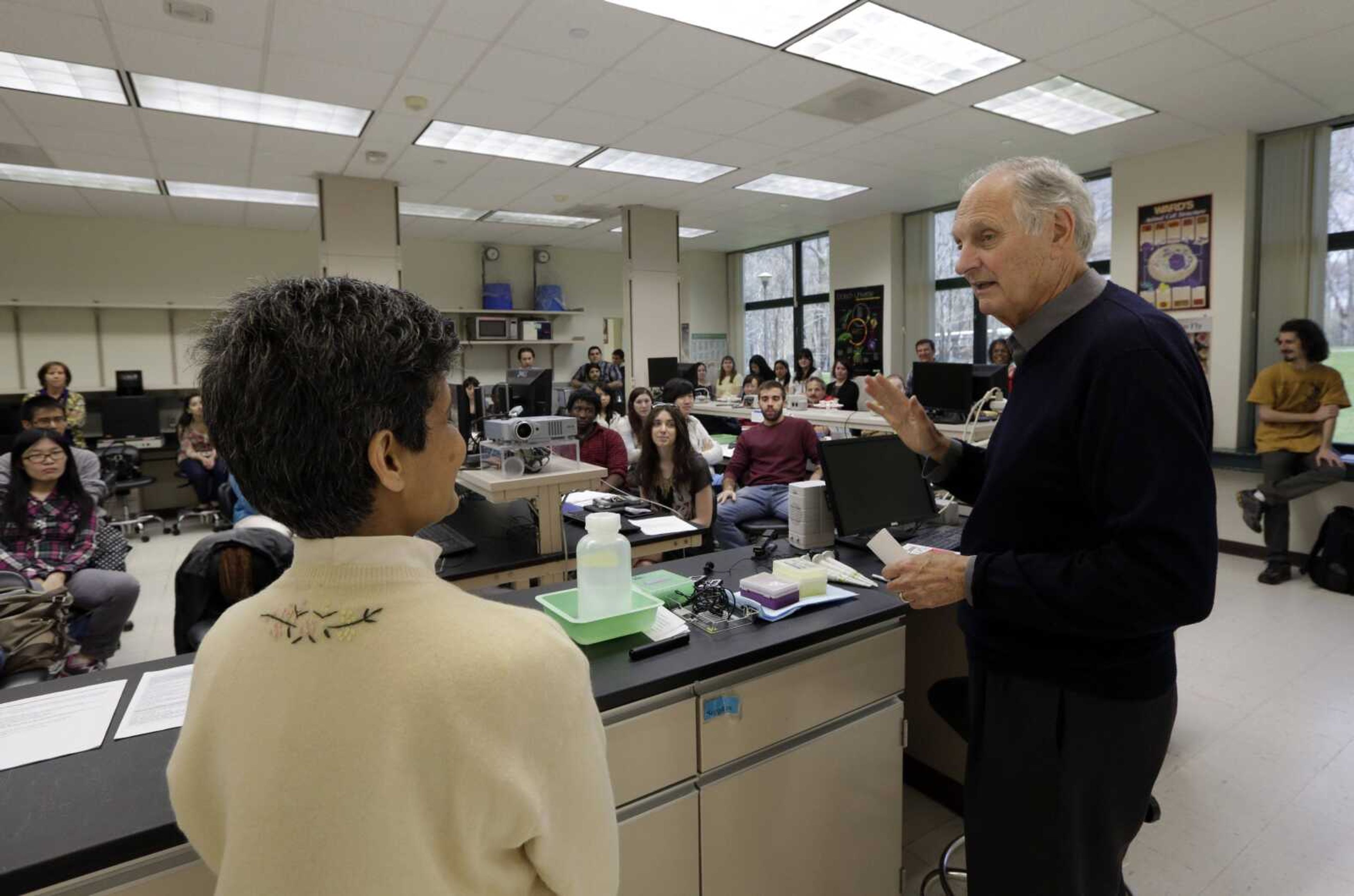

The center launched in 2009. At a gala last week, the Long Island school officially renamed it the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science.

"Alan did not casually lend his celebrity to this effort," said Stony Brook President Dr. Samuel Stanley. "He has been a tireless and full partner in the center since its inception. During the past four years, he has traveled thousands of miles championing its activities. ... He has helped train our faculty and develop our curriculum, and he personally teaches some workshops."

Alda also has helped publicize a contest the center sponsored the last two years asking students and scientists throughout the country to find simple ways to explain such concepts as "What is a flame?" or "What is time?"

Among the courses taught by the center is an improvisational acting class that teaches scientists ways of communicating their thoughts clearly to others.

"We've learned it's important to set up vivid analogies," said Lyle Tomlinson, a 24-year-old neuroscience graduate student from Brooklyn who's working as a teaching assistant, noting he used the effects of caffeine in a morning cup of coffee to begin a discussion on the nervous system.

Rep. Steven Israel, whose district includes the Stony Brook campus, said educating people on the importance of science is key to America's competitiveness in the 21st century economy.

He recalled watching a congressional hearing on climate change in which, he said, "a bunch of scientists were trying to teach congressmen about the science of climate change and the congressmen were trying to teach the scientists about politics. It was as if both sides were speaking alien languages."

Alda shared what he called his best examples of clear communication with Tomlinson and his fellow teaching assistants.

About a decade ago, Alda said, he was in Chile filming a segment for "Scientific American Frontiers" when he was stricken with sharp stomach pains. He was evacuated from an 8,000-foot observatory and taken in an old rickety ambulance to a small, dimly lit clinic, where a doctor examined him and said he would require lifesaving surgery.

"Some of your intestine has gone bad, and we have to cut out the bad part and sew the two good ends together," the physician explained.

"And I said, ‘You're going to do an end-to-end anastamosis.' He said, ‘How do you know that?' And I said, ‘Oh I did many of them on ‘M.A.S.H.' That was the first operation I learned about on M.A.S.H."'

After the classroom erupted in laughter, Alda concluded:

"He didn't waste any time on me trying to figure what he was talking about. He said it in the clearest terms possible. He didn't sacrifice any accuracy by making it clear."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.