More to explore

-

-

-

Local News 5/15/24Cost savings appear at heart of potential contract change between City, ChamberThe City of Cape Girardeau could save $164,327 annually by merging Visit Cape and the municipal Parks and Recreation Department, according to a proposal obtained by the Southeast Missourian. The proposal, put forth by the city’s Parks and Recreation...

Local News 5/15/24Cost savings appear at heart of potential contract change between City, ChamberThe City of Cape Girardeau could save $164,327 annually by merging Visit Cape and the municipal Parks and Recreation Department, according to a proposal obtained by the Southeast Missourian. The proposal, put forth by the city’s Parks and Recreation... -

Local News 5/15/24Woman sets up donation drive for cat that needs leg amputated after being shot in Cape neighborhood2A Cape Girardeau woman has set up a fundraiser to get care for a neighborhood cat she named Garfield, who she says was shot in the leg. Madelyn Bandermann took to social media to share that an outside cat that she feeds and cares for was missing for...

Local News 5/15/24Woman sets up donation drive for cat that needs leg amputated after being shot in Cape neighborhood2A Cape Girardeau woman has set up a fundraiser to get care for a neighborhood cat she named Garfield, who she says was shot in the leg. Madelyn Bandermann took to social media to share that an outside cat that she feeds and cares for was missing for... -

Local News 5/15/24Lutheran Family and Children's Service to hold mental health awareness lunch FridayMental health information will be at the forefront of an upcoming Lutheran Family and Children’s Services of Missouri (LFCS) event. In honor of May being Mental Health Awareness Month, the organization is hosting Mental Health: Let’s Taco 'Bout It...

Local News 5/15/24Lutheran Family and Children's Service to hold mental health awareness lunch FridayMental health information will be at the forefront of an upcoming Lutheran Family and Children’s Services of Missouri (LFCS) event. In honor of May being Mental Health Awareness Month, the organization is hosting Mental Health: Let’s Taco 'Bout It... -

Local News 5/15/24SEMO transitioning from Horizons Enrichment Center to new provider1Southeast Missouri State University is transitioning services provided by the Horizons Enrichment Center to a new, yet-to-be-named provider, pending approval by the Missouri Department of Mental Health. The university will continue to operate the...

Local News 5/15/24SEMO transitioning from Horizons Enrichment Center to new provider1Southeast Missouri State University is transitioning services provided by the Horizons Enrichment Center to a new, yet-to-be-named provider, pending approval by the Missouri Department of Mental Health. The university will continue to operate the... -

Local News 5/15/24Guardians of Liberty to host Meet the Candidates event3Guardians of Liberty in Southeast Missouri will host a Meet the Candidates event on Tuesday, May 21. The news release states the public is invited to this free event. According to the news release, more than two dozen candidates in the Aug. 6...

Local News 5/15/24Guardians of Liberty to host Meet the Candidates event3Guardians of Liberty in Southeast Missouri will host a Meet the Candidates event on Tuesday, May 21. The news release states the public is invited to this free event. According to the news release, more than two dozen candidates in the Aug. 6... -

Local News 5/15/24Scout Hall's next act: Melissa Carper's genre-blending soundMelissa Carper started her music career young. From singing gospel music weekly with her family at rest homes and in church to singing at clubs, such as the Eagles and American Legion by age 12. Growing up around music shaped Carper and her sense of...

Local News 5/15/24Scout Hall's next act: Melissa Carper's genre-blending soundMelissa Carper started her music career young. From singing gospel music weekly with her family at rest homes and in church to singing at clubs, such as the Eagles and American Legion by age 12. Growing up around music shaped Carper and her sense of... -

-

-

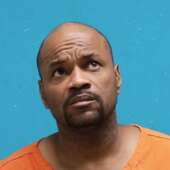

Local News 5/14/24Cape Girardeau County coroner waives hearing in criminal case8Cape Girardeau County Coroner Wavis Jordan waived a preliminary hearing in his ongoing criminal case in Cape Girardeau County Court on Tuesday, May 14. A preliminary hearing is a standard practice for the prosecution to give evidence to convince a...

Local News 5/14/24Cape Girardeau County coroner waives hearing in criminal case8Cape Girardeau County Coroner Wavis Jordan waived a preliminary hearing in his ongoing criminal case in Cape Girardeau County Court on Tuesday, May 14. A preliminary hearing is a standard practice for the prosecution to give evidence to convince a... -

Local News 5/14/24Jackson man faces charges after allegedly threatening to kill victim, burn house downA Jackson man is in jail after a victim told police he threatened to kill her and burn down the house after previous reports of abuse. Bradley J. Moreland, 41, faces Class E felony charges of third-degree domestic assault and first-degree...

Local News 5/14/24Jackson man faces charges after allegedly threatening to kill victim, burn house downA Jackson man is in jail after a victim told police he threatened to kill her and burn down the house after previous reports of abuse. Bradley J. Moreland, 41, faces Class E felony charges of third-degree domestic assault and first-degree... -

Local News 5/14/24Sex offender arrested on allegations of repeatedly approaching children at Cape Girardeau park2A convicted sex offender living in Cape Girardeau is in jail in lieu of $25,000 cash-only bond after being accused of approaching children at a park. Cape Girardeau Police officers responded to a call on Sunday, May 12 from parents concerned that...

Local News 5/14/24Sex offender arrested on allegations of repeatedly approaching children at Cape Girardeau park2A convicted sex offender living in Cape Girardeau is in jail in lieu of $25,000 cash-only bond after being accused of approaching children at a park. Cape Girardeau Police officers responded to a call on Sunday, May 12 from parents concerned that... -

Local News 5/14/24Road work: Seal coat operations to impact Perry County traffic; Route C in Perry, Cape counties to be seal coatedSeal coat operations to impact in Perry County traffic Missouri Department of Transportation crews will be seal coating roads in Perry County, according to a MoDOT news release. The roads impacted by the surface improvements are n Route K, from...

Local News 5/14/24Road work: Seal coat operations to impact Perry County traffic; Route C in Perry, Cape counties to be seal coatedSeal coat operations to impact in Perry County traffic Missouri Department of Transportation crews will be seal coating roads in Perry County, according to a MoDOT news release. The roads impacted by the surface improvements are n Route K, from... -

-

Local News 5/13/24Notre Dame creating 'servant leaders' through partnership with Chick-fil-A1Notre Dame Regional High School partnered with Chick-fil-A during the 2023-24 school year to teach students the importance of "servant leadership" through the company's Leader Academy program. On Friday, May 10, Chick-fil-A Leader Academy...

Local News 5/13/24Notre Dame creating 'servant leaders' through partnership with Chick-fil-A1Notre Dame Regional High School partnered with Chick-fil-A during the 2023-24 school year to teach students the importance of "servant leadership" through the company's Leader Academy program. On Friday, May 10, Chick-fil-A Leader Academy... -

Local News 5/13/24Ex-Sikeston cop receives 20-year sentence for child sexual abuse charges2A former Sikeston, Missouri, police officer was sentenced to 20 years in the Missouri Department of Corrections after his conviction of statutory rape of a child younger than than 14 years old. Brian L. Robinson was sentenced on May 3 to 20 years on...

Local News 5/13/24Ex-Sikeston cop receives 20-year sentence for child sexual abuse charges2A former Sikeston, Missouri, police officer was sentenced to 20 years in the Missouri Department of Corrections after his conviction of statutory rape of a child younger than than 14 years old. Brian L. Robinson was sentenced on May 3 to 20 years on... -

Local News 5/13/24County commissioners updated on renovations for Melaina's Magical Playland2Melaina’s Magical Playland will be undergoing some renovations in the near future. During the Monday, May 13, meeting of the Cape Girardeau County Commission, the county’s park superintendent, Bryan Sander, notified the commissioners about replacing...

Local News 5/13/24County commissioners updated on renovations for Melaina's Magical Playland2Melaina’s Magical Playland will be undergoing some renovations in the near future. During the Monday, May 13, meeting of the Cape Girardeau County Commission, the county’s park superintendent, Bryan Sander, notified the commissioners about replacing... -

-

-

-

-

-

Local News 5/11/24Cape Girardeau County election officials, public view voting machine demonstrations11Three election equipment companies made their pitches to both members of the public and Cape Girardeau County's election team as to why they should choose their voting machines for upcoming elections.

Local News 5/11/24Cape Girardeau County election officials, public view voting machine demonstrations11Three election equipment companies made their pitches to both members of the public and Cape Girardeau County's election team as to why they should choose their voting machines for upcoming elections. -

Local News 5/11/24Cape Girardeau Parks and Recreation to operate Visit Cape starting at the end of June 302The City of Cape Girardeau has negotiated the terms of its contract with the Cape Girardeau Area Chamber of Commerce to operate the Convention and Visitor’s Bureau/Visit Cape. The Parks and Recreation Department will now operate the bureau starting...

Local News 5/11/24Cape Girardeau Parks and Recreation to operate Visit Cape starting at the end of June 302The City of Cape Girardeau has negotiated the terms of its contract with the Cape Girardeau Area Chamber of Commerce to operate the Convention and Visitor’s Bureau/Visit Cape. The Parks and Recreation Department will now operate the bureau starting... -

Local News 5/11/24CCC unveils new branding during 50-year anniversary celebratory luncheonsCommunity Counseling Center celebrated its 50th anniversary with a commemorative luncheon on Friday, May 10, at the Jackson Civic Center, along with an unveiling of the organization’s rebranding. CCC held luncheons throughout the week at each of the...

Local News 5/11/24CCC unveils new branding during 50-year anniversary celebratory luncheonsCommunity Counseling Center celebrated its 50th anniversary with a commemorative luncheon on Friday, May 10, at the Jackson Civic Center, along with an unveiling of the organization’s rebranding. CCC held luncheons throughout the week at each of the... -

-

Local News 5/10/24Judge denies request for cameras in the courtroom to cover coroner's criminal hearing3A judge has denied a request to allow cameras or recording equipment in the courtroom as the Cape Girardeau County coroner faces criminal charges. KFVS anchor and media coordinator for the 32nd Circuit Kathy Sweeney had asked in March, per the rules...

Local News 5/10/24Judge denies request for cameras in the courtroom to cover coroner's criminal hearing3A judge has denied a request to allow cameras or recording equipment in the courtroom as the Cape Girardeau County coroner faces criminal charges. KFVS anchor and media coordinator for the 32nd Circuit Kathy Sweeney had asked in March, per the rules... -

Local News 5/10/24Facing a nationwide trend, SEMO takes proactive steps against looming budget shortfalls17Amid universities around the country facing financial problems, largely impacted by lower enrollment numbers, Southeast Missouri State University is working to avoid potential budget issues that could arise in the near future. According to...

Local News 5/10/24Facing a nationwide trend, SEMO takes proactive steps against looming budget shortfalls17Amid universities around the country facing financial problems, largely impacted by lower enrollment numbers, Southeast Missouri State University is working to avoid potential budget issues that could arise in the near future. According to... -

-

-

Most read 5/9/24Deceased Cape teacher serves as motivation for Tough Mudder competitor1Tough Mudder is a hardcore obstacle course designed to test participants’ all-around strength, stamina and mental grit, and runners must be at least 14 years old. Mildred Wilson has no problem meeting the criteria. Wilson, 85, was a spry 80 when she...

Most read 5/9/24Deceased Cape teacher serves as motivation for Tough Mudder competitor1Tough Mudder is a hardcore obstacle course designed to test participants’ all-around strength, stamina and mental grit, and runners must be at least 14 years old. Mildred Wilson has no problem meeting the criteria. Wilson, 85, was a spry 80 when she... -

Most read 5/9/24City of Cape signs lease agreement for police substation on Good Hope12A lease agreement between the City of Cape Girardeau and not-for-profit organization Partners for Good Hope for a police substation at 629 Good Hope St. was approved by the City Council on Monday, May 6. According to the council’s agenda report, the...

Most read 5/9/24City of Cape signs lease agreement for police substation on Good Hope12A lease agreement between the City of Cape Girardeau and not-for-profit organization Partners for Good Hope for a police substation at 629 Good Hope St. was approved by the City Council on Monday, May 6. According to the council’s agenda report, the... -

Most read 5/9/24Kiss in gas station parking lot leads to felony weapons charge, documents say10A Cape Girardeau man faces felony charges after police say he used a gun to shatter a victim’s driver’s-side car window. Adam Childers, 37, faces charges of second-degree property damage and unlawful use of a weapon (exhibiting), which is considered...

Most read 5/9/24Kiss in gas station parking lot leads to felony weapons charge, documents say10A Cape Girardeau man faces felony charges after police say he used a gun to shatter a victim’s driver’s-side car window. Adam Childers, 37, faces charges of second-degree property damage and unlawful use of a weapon (exhibiting), which is considered...