Life Without: Chapter 1, the confession

In August 2004, Butch Johnson, an investigator with the Missouri Public Defender's office, sat down with 21-year-old Romanze Mosby in an interview room at South Central Correctional Center in Licking, Missouri. Johnson sought to elicit information that could help his client, David Robinson, then 36, of Sikeston, Missouri...

The following story is one installment of an investigative series of the questionable conviction of David Robinson, who is accused of shooting Sheila Box in 2000. Please read all our other related stories and view our video series at www.semissourian.com/lifewithout.

In August 2004, Butch Johnson, an investigator with the Missouri Public Defender's office, sat down with 21-year-old Romanze Mosby in an interview room at South Central Correctional Center in Licking, Missouri.

Johnson sought to elicit information that could help his client, David Robinson, then 36, of Sikeston, Missouri.

Robinson had been convicted of first-degree murder in 2001 for the death of 36-year-old Sheila Box the previous year.

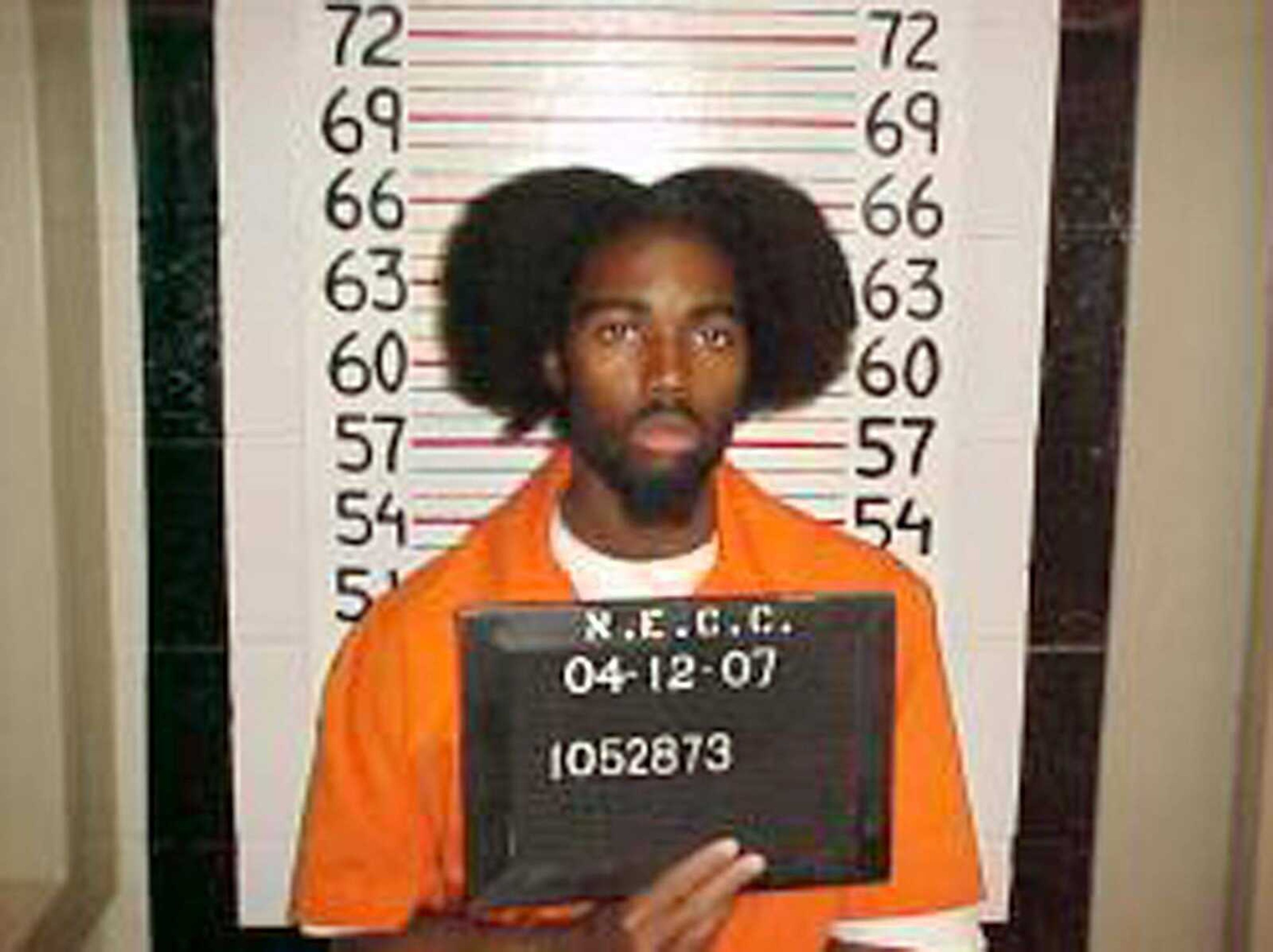

Mosby was in the middle of a 10-year prison sentence for unlawful use of a weapon in 2000 and first-degree assault in 2001.

"Why don't you tell me what happened on Aug. 5, 2000, at the -- close to the intersection (of) Ruth and Branum?" Johnson asked.

"I was in my uncle's yard at 845 Ruth, and when (she) came through in a gray Suburban," Mosby said. "She asked for some crack and stuff, and I asked, I like, I got it and started towards the truck.

"I didn't go all the way up on it ... and I seen the guns, the gun, and I left and stuff. I started, 'Throw the money, throw the money out,' and I'm gonna throw her the dope, and then ... I seen a little flash. I was walking up to it, and she just raised her arm, and that's when I shot her."

Johnson, seeking clarification, repeated, "And then all of a sudden you saw the silver chrome flash, as it was brought up?"

"... I was walking up to her, and I looked, and she must have thought I was gonna rob her or something, and that was when I shot her, but she would have shot me," Mosby said.

April 2016

The family room at Jefferson City Correctional Center has a mural on one wall featuring cartoon characters such as Mario, Wreck-It Ralph and Looney Toons on top of a blue sky and green hills.

Outside the windows on that wall, spools of barbed wire reflect harshly in the midday sun.

David Robinson, now 48, walks out of the door that leads back to the main part of the prison, carrying a folder full of documents. He is wearing a white T-shirt and gray pants. His hair is closely cropped to his scalp.

At 6-foot-3 and nearly 300 pounds, Robinson cuts an imposing figure. It's not hard to flash back to 1983, when he was sent to prison as an adult at 15 years old.

The way former Scott County jailer Jim Chambers tells it, Robinson was beating up inmates twice his age when he was in county the first time.

His physique and attitude have softened a little over time.

When he was younger, Robinson felt he had to prove his mettle in confrontations with other inmates. Being locked up for so long, he's learned to let the little slights go. His family has tried to see him as often as possible, and Robinson loses all his privileges if he causes trouble.

He also has been too busy to get involved with prison politics. Robinson has been consumed with the legal work on his own case.

Although he's an expert, the case is still dumbfounding. Both witnesses who testified against him have recanted. Another man has confessed to committing the crime.

Sikeston police took Robinson's clothes from the night of the murder and tested them for gunshot residue and DNA. Investigators found a spot of blood on his hat, but lab analysis determined it was his own.

Police confiscated Robinson's car, an old Buick, and the car he was driving late that August night in 2000. The car belonged to Corey Turner. Neither car produced physical evidence.

Neither a murder weapon nor a shell casing was found.

At Robinson's trial, three people provided testimony that countered the statement of Albert Baker, the primary witness. Another three refuted Baker's testimony in later depositions.

Eight people testified on Robinson's behalf at his original trial.

Two people -- including one sheriff's deputy quoting a confidential informant -- testified Mosby was the shooter. Four more people later testified in depositions Mosby confessed to shooting Box.

The state's entire case was built on the word of two admitted drug addicts who have recanted since.

Those hundreds of pages inside Robinson's folder offer hope for a man who already has served 16 years of a life sentence, but Robinson remains in prison.

Robinson says he has put aside his anger toward the police and prosecutors. He's frustrated and exasperated.

His case is before the Missouri Supreme Court, but Robinson still is waiting for a decision.

"I'm still trying to figure this whole thing out, man," he says.

August 2001

Law-enforcement personnel were aware of Mosby's potential involvement in Box's death at least as far back as May of 2001.

At Robinson's trial, Scott County sheriff's deputy Bobby Sullivan testified a confidential informant, Dion Savage, told him Mosby was the killer, the shooting happened near the corner of Ruth Street and Branum Avenue, and the murder weapon was dumped in Upper Big Lake or a ditch near it.

Sullivan was part of a team that dived into the lake and nearby ditches, looking in vain for the black .380 Savage described as the murder weapon.

Mosby, 18 at the time, testified during Robinson's trial he had talked to his cousin, Carlos Jones, in prison two months earlier, and Jones had told him he shot Box.

Another witness, Kerenzo Hill, testified Jones told him while they were locked up that Mosby shot Box.

But the jury never heard testimony about Mosby. The jurors were removed from the courtroom during Sullivan, Mosby and Hill's testimony, and Judge Fred Copeland found the testimony was hearsay and thus inadmissible as evidence.

January 2004

Jones testified during a 2004 deposition he was at his uncle's house the night of the murder, behind Mosby on the porch, and saw Mosby shoot Box. He was in prison in 2004 at Algoa Correctional center in Jefferson City for attempted robbery.

"I was standing in the yard of my uncle's house, and it's dark," Jones said. "...There was a Suburban there and a there was a guy there, and I heard a gunshot."

Jones said he did not know Mosby was the shooter until two days later.

"When I seen him, he told me the lady had a chrome .38 or something, said she had it in her hand or her lap or something," Jones said. "He was telling me about that. And one thing led to another, and he shot her."

Jones was one of the first people Mosby told about shooting Sheila Box, but he was not the last.

Mosby confessed to investigator Johnson, and he also confessed to three inmates he served time with in Licking from 2002 to 2005: Vincent Hines, Donald Triblett and Michael Richardson, all of whom provided signed affidavits in 2011.

Each of them told roughly the same story: Mosby said he was involved in a drug deal gone bad and shot Box in self-defense.

In each story, the inmates talked about the guilt that was weighing on Mosby.

Hines wrote Mosby's face showed sorrow after he said he shot Box.

"He said but (what) was really f*****-up is they charged the wrong dude, that they convicted another dude for killing her," he wrote.

Triblett noticed Mosby had cut his long hair, had become "real skinny" and often appeared depressed.

"All the while, Romanze was telling me this, it was as if he needed to get it off his chest," he wrote in the affidavit.

Richardson, who was convicted of manslaughter, noticed Mosby had stopped leaving his cell and started acting differently around inmates from the Bootheel area.

Eventually, Mosby asked Richardson how he was able to receive manslaughter in his case.

"Mr. Mosby said that he shot the woman that Mr. Robinson was locked up for, but he had done it in self-defense because he thought that the woman was going to rob him, but he was scared to tell anyone," Richardson wrote. "He then said that he told the people who came to visit him the same thing, and while he was telling me that, he started to cry."

Richardson told Mosby he had done the right thing by confessing, and if he kept the information to himself, he would be OK with other inmates.

"I told him it's not the end of the road," Richardson wrote.

2009

Mosby's confession was what made Robinson's case so compelling for lawyers at the Bryan Cave Law Firm.

Lee Marshall was the first lawyer to show interest. He was running an appellate clinic at Washington University, and his students were working on a federal case but getting nowhere. At this point, though, they had the confession from Mosby and a recantation from one witness.

Marshall brought the case back to his colleagues at Bryan Cave, a prominent St. Louis law firm, including Jim Wyrsch. Wyrsch, Stephen Snodgrass and Charles Weiss had worked on Joshua Kezer's case, also originating in Scott County. Judge Richard Callahan recently had found Kezer innocent of first-degree murder. Witnesses also had recanted in that case, but there were also procedural errors made by the prosecution.

However, Kezer's case was left unsolved. In Robinson's case, Robinson's law team had evidence on the actual killer -- his own voice, in fact.

"It certainly, to us, spoke mountains, volumes about David's innocence," Wyrsch said. "The difference between this case and other habeas cases is you have just about everything you'd ever want. For example, the Kezer case, another one we worked on, he was found innocent by the court, but we never answered the question who did it. ... That's still something that nags me. ... In this case, you have two witnesses at trial, one a jailhouse snitch -- [jailhouse snitches] are generally worthless -- and he recants. One eyewitness who had questions about his reliability from the get-go, but he put that all behind him because he completely and utterly recanted his testimony, admitted he lied. And then on top of that, you have a confession by someone else. And not only a confession by someone else, but a confession that makes sense of the rest of the evidence."

Bryan Cave lawyers met with Robinson in 2009 and agreed to take the case pro bono.

The firm's lawyers already had a rapport with then-Southeast Missourian crime reporter Bridget DiCosmo, who wrote about the Kezer case. Before they decided to file a federal habeas corpus petition, they provided information about the case to DiCosmo, and she wrote a story about the law team picking up the case.

June 19, 2009

Mosby had two months left on his prison time and found himself in the library of Algoa prison, reading the Sikeston Standard-Democrat.

This particular issue had DiCosmo's story detailing Robinson's case for innocence, including information about Mosby confessing to the crime in 2004.

Mosby had been in prison about as long as Robinson at this point, but any joy he had felt about getting out soon was gone.

Mosby was serving time with his stepfather, Kelvin Howard, in Algoa. Howard, who raised Mosby from birth with his mother, Dorothy Mosby, had a few months remaining on a possession charge.

Howard and Mosby walked in the yard June 19, and their conversation turned heavy.

In a recorded 2012 interview with Johnson, the investigator, Howard recalled the conversation.

"Tell me the truth. What's going on?" Howard asked.

"David did not do this crime," Mosby said.

"What you mean?" Howard asked. "All these years, you sit back and let him be in prison for something he ain't done?"

"What should I do?"

"Well, did you do it?"

Mosby looked Howard in his eyes. "Yes."

Howard said Mosby changed the subject, and they took a picture to send to Dorothy Mosby.

"What are you gonna do?" Howard asked.

"If I tell the truth, I'll never be around no more," Mosby said.

Howard said he and Mosby spent the rest of the day together and took several pictures. He said Mosby chose not to play basketball that day because he was confused and upset.

Before they parted ways, Mosby asked Howard to please take care of his mother.

"Right then, there was nothing I could do," Howard said. "I kinda figured something was gonna go wrong."

The guards woke Howard about 1 a.m. to tell him Mosby had hanged himself in his cell.

"He couldn't take it no more," Howard said. "But he figured that was the best thing to do."

Howard did not talk to Johnson, the investigator, until Nov. 24, 2012, after Dorothy Mosby died of cancer. He said he had promised her not to talk about Box's murder, though he is a distant cousin to Robinson. Howard also shared a cell with Robinson before Robinson's trial.

"I think he would want the truth to come out now," Howard said in a deposition from 2015. "That's why he told me, because he knew sooner or later, I would speak the truth for him."

Wyrsch and the attorneys thought they had plenty of time to subpoena Mosby and get his confession under oath. Mosby's suicide made them reset their strategy on Robinson's case.

"It got us kind of deflated," Wyrsch said. "It kind of put the skids on that for awhile. It stalled things for a little bit."

While Wyrsch stayed on, Marshall and the other lawyers moved away from St. Louis or took other jobs away from Bryan Cave in the next six months.

Mosby's confession was not under oath. As with Mosby's testimony during Robinson's trial, assistant attorney general Katharine Dolin argued his audiotaped confession and all of the subsequent confessions were hearsay.

Now Robinson's lawyers were looking at a steeper obstacle: getting the primary witness against him to recant on the record.

bkleine@semissourian.com

(573) 388-3644

Editor's note: This project was made possible by the support of Southeast Missouri State University. Among its award-winning programs are Criminal Justice and Sociology, Mass Media and Social Work.

Pertinent address: 8200 No More Victims Road, Jefferson City, MO