Opinion: The electric horseless carriage

I suppose there are always those things in a person’s life that mark a major shift in the way the world of tomorrow will function moving forward. I recall my grandmother reminiscing about seeing her first talking motion picture as a child and my mother recalling the installation of their first television set in their home. I suppose I can tell my future grandchildren about the first mobile bag phone I carried that was the size of a small suitcase.

I had that same realization as we installed the first public electric automobile charging station in downtown Cape Girardeau on the parking lot at Century Casino. The world is changing again, and the new normal will be filled with electric modes of transportation.

For more than 120 years, the internal combustion engine has dominated, but are we on the verge of seeing that reign finally ending? And what does that mean for everything we associate with the automobile as we know it? Will the gas station go the way of the hitching post?

It is probably something that will bring as much heated discussion as the potholes caused by those same automobiles. Some will agree electric cars are the future, while others will disagree.

Perhaps the best perspective about our future can be found by looking back at those who were pondering these same questions when faced with another dramatic change: the end of the horse age.

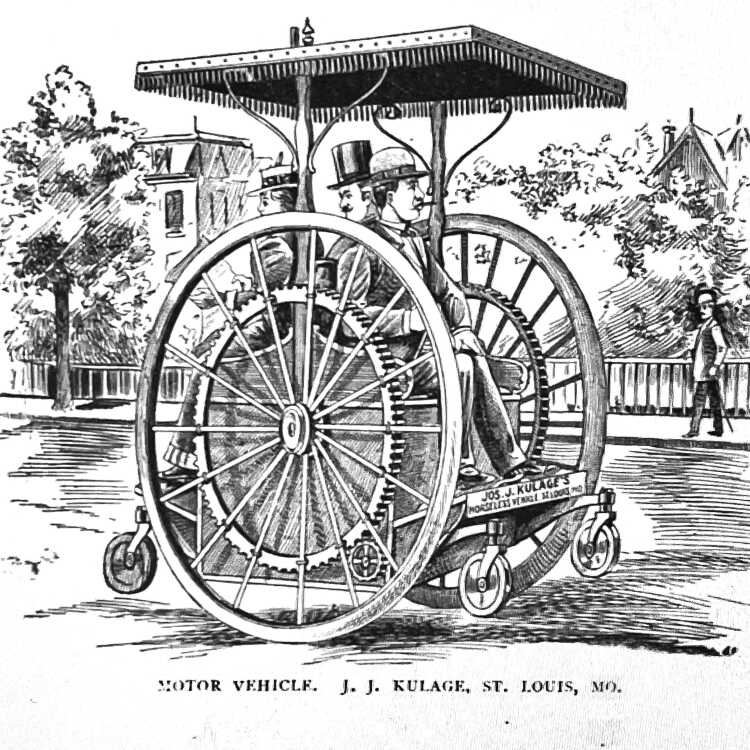

The newspapers of the mid-1890s were filled with predictions of the future and reports of new inventions that would potentially change daily life. Many of these reports included self-propelled modes of transportation. At the time, the terminology was not yet clear, and some creative suggestions were made for the names of these new inventions.

The “horseless carriage” became the popular term, but before that time, other suggestions included the “unpedaled vehicle,” “electric horse,” “locomotor” or “auto truck.”

In August 1895, the Marble Hill newspaper ran an item that also appeared in several other newspapers of the day. The first line read, “A fit name for the horseless carriage has not been found.” The term “motocycle” — no “r” in this one — was suggested, along with “autocycle” or “selfwheeler.”

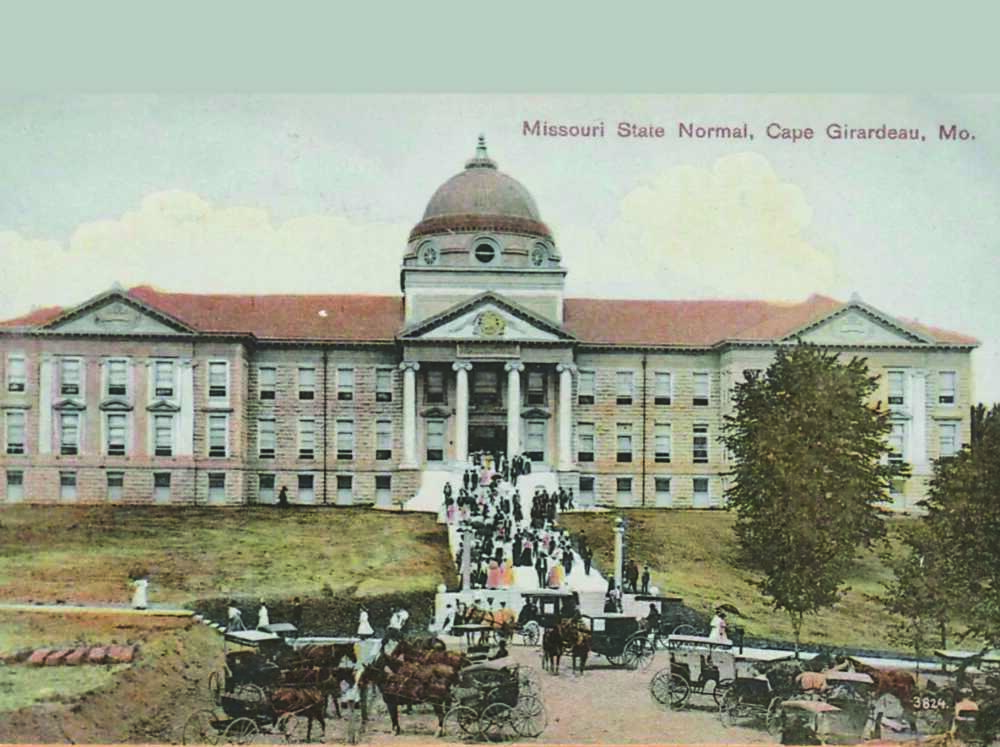

At this time, few people in the United States had ever seen a horseless carriage, but it was widely predicted they would soon replace the horse-drawn “cabs” and “Victorias” of the day — once common terms for carriages that have now been rendered defunct.

The technology had not yet progressed to the point of determining the dominant types of propulsion. In the earliest days, the suggested motive of apparatus varied from steam power to electric battery, heated vapor or compressed gas. Various fuel sources were considered, including acetylene, ether, kerosene, naphtha, oil and even dynamite. One inventor designed a vehicle using spring power — visualize a giant wind-up toy — and then added an electric motor to wind the spring.

Horseless Age, the leading industry publication of the time, suggested the term “motor” be used for these new vehicles and “engine” be reserved for more industrial applications.

The earliest carriages and wagons, mostly derived from similar efforts in Europe, were powered by electric or steam. Even as we see electric power as the future now, as early as 1895, claims were made that electric-powered horseless carriages were being built that could move faster than a horse-drawn wagon. Yet another claim of the time was a machine that was capable of traveling 180 miles without having to replenish the electrical battery.

The main obstacle discussed seemed to be the establishment of electric power stations along routes. One newspaper reported, “It is likely that we will soon see these electric stations replace the watering-troughs of today.”

Others suggested electric batteries could be continually charged from a wire strung overhead, or a wire or rail on the road itself would be energized to power the machine. In this case, new cable or electric roads would be needed.

The most practical approach seemed to be the use of electric storage batteries that could be charged by stopping occasionally and connecting to a wire dropped from a nearby telephone or telegraph line. Some inventors were already claiming to have invented a motor that could charge its own storage battery when traveling downhill.

Others moved away from electric power, and some suggested the horse was still the best way to power the new machines. Similar to how the bicycle was invented to use the human body to propel itself more efficiently, these inventors felt a similar approach could be taken with horses. While not suggesting a horse could ride a bicycle, the inventors suggested a mechanism where the horse could be lifted off the ground and used to generate power for the machine. It was claimed that with the proper gearing, great speed could be achieved.

Even if the mode of power was established, other ideas emerged about how the machine would most efficiently move. While some suggested wooden or steel wheels, others suggested wheels with a pneumatic tire. Another idea was the steel wagon road, a steel rail approximately five inches wide and in the shape of the gutter, that would certainly be preferred over a dirt or even brick-paved road. The inventor claimed the steel rail was 20 times more efficient as driving over the ground and suggested both city streets and farm rows would all have steel rails in the future. He predicted the horseless wagons used on the rails would be made of aluminum, and the invention would revolutionize agriculture.

Most realized the importance of the development of roads from an early stage. The construction of first-class roads was a necessity in the development of the horseless carriage.

Other concerns were also soon addressed, including an inventor announcing the arrival of the hitching post for the horseless carriage. The device was called a “hitching rope,” and the inventor claimed no vehicle should be without one. It was simply a wire cable with a padlock to properly secure a horseless carriage. “With more people learning to operate the machines, it is unwise to leave one unattended on the street,” it was said.

Another question surfaced to determine which word could be used to describe a private collection of automobiles or place to house them, something equivalent to a “stable” of horses. Several suggestions were given, such as “autobarn,” “motorome” or “motorden, or even “motorium” or “motorshed.” The French word “garage” was dismissed, it was claimed, because it had already come into use as a place to have an automobile repaired.

Even more forward thinkers of the time were already describing the future of horseless carriages that were capable of flying in the air, calling them “sky motors” or “airships.”

All of the discussion about the new machines was not without controversy. In early 1899, a Caruthersville, Mo., newspaper commented about those claiming the horse was about to become a thing of the past in that city — “the inventors ‘auto’ give us more invention and less talk!”

One newspaper warned there would be much suffering of humanity because of these new inventions, and it was claimed that timid people would avoid the street because of the machines. The ringing of bells on bicycles, it was foreseen, would soon be replaced with the loud roaring of engines. Some were more direct in writing of the “evils of the automobile,” and in those early days, some reported there was already evidence of the many diseases resulting from the auto wagons.

The conflicting opinions about the new machines resulted in a Jackson newspaper reporting in 1906 that owning an automobile was “a good way to become unpopular.” Whether unpopular or not, by the next decade, the automobile had emerged as the preferred form of transportation. The same will likely hold true for electric vehicles over our next decade. I suppose the only way to know for sure is to keep this newspaper until 2032, and then check to see if terms like frunk, regen and RPH have replaced the trunk, gas cap and MPG.