Bodies of knowledge: Doctors in training still learning from cadavers

WASHINGTON -- Color-coded denim cloths cover the row upon row of black body bags atop cold metal tables. Blue means a body that eventually will go into a common grave. Tan, the family wants those remains back for burial, eventually. These are bodies donated to science. Before first-year medical students lay their hands on the living, they learn anatomy from the dead...

WASHINGTON -- Color-coded denim cloths cover the row upon row of black body bags atop cold metal tables. Blue means a body that eventually will go into a common grave. Tan, the family wants those remains back for burial, eventually.

These are bodies donated to science. Before first-year medical students lay their hands on the living, they learn anatomy from the dead.

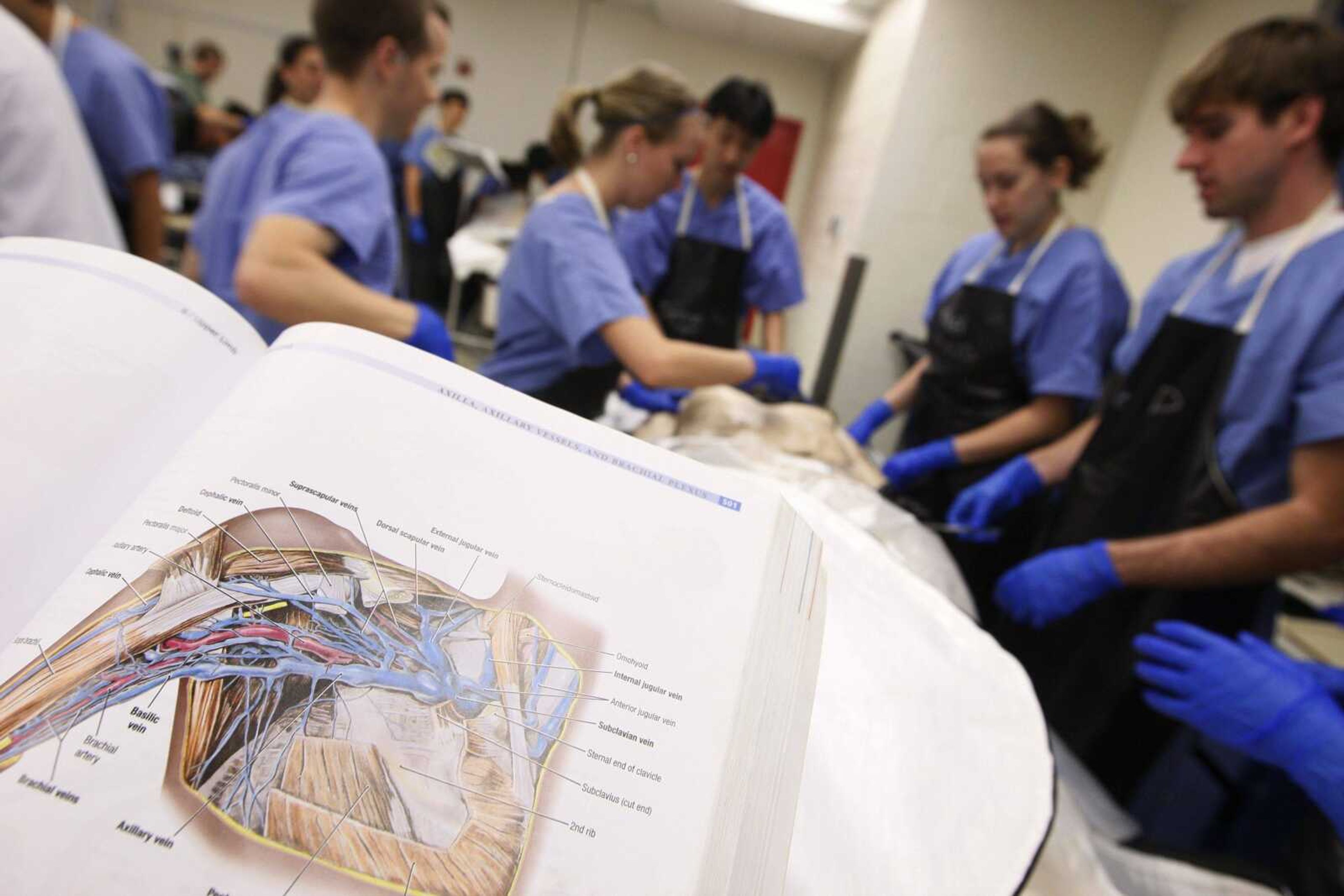

Week after week, for six months, teams of students will file into in a laboratory at Georgetown University to slowly take apart "their" body.

First goes the skin on the back. They lay bare the spinal cord and marvel at how its lower roots resemble the tail of a horse. Carefully probing a lump inside one chest, a team unearths what at first looks like a metal button -- a port through which this man once received chemotherapy.

The room quiets as students unwrap the protective covering over each hand. One torso, they quickly learn, looks pretty much like another. But a hand is unique, somehow more intimate, as they hold it with their own blue-gloved hands. Many of the women's nails still bear polish. One year, students found a wedding ring.

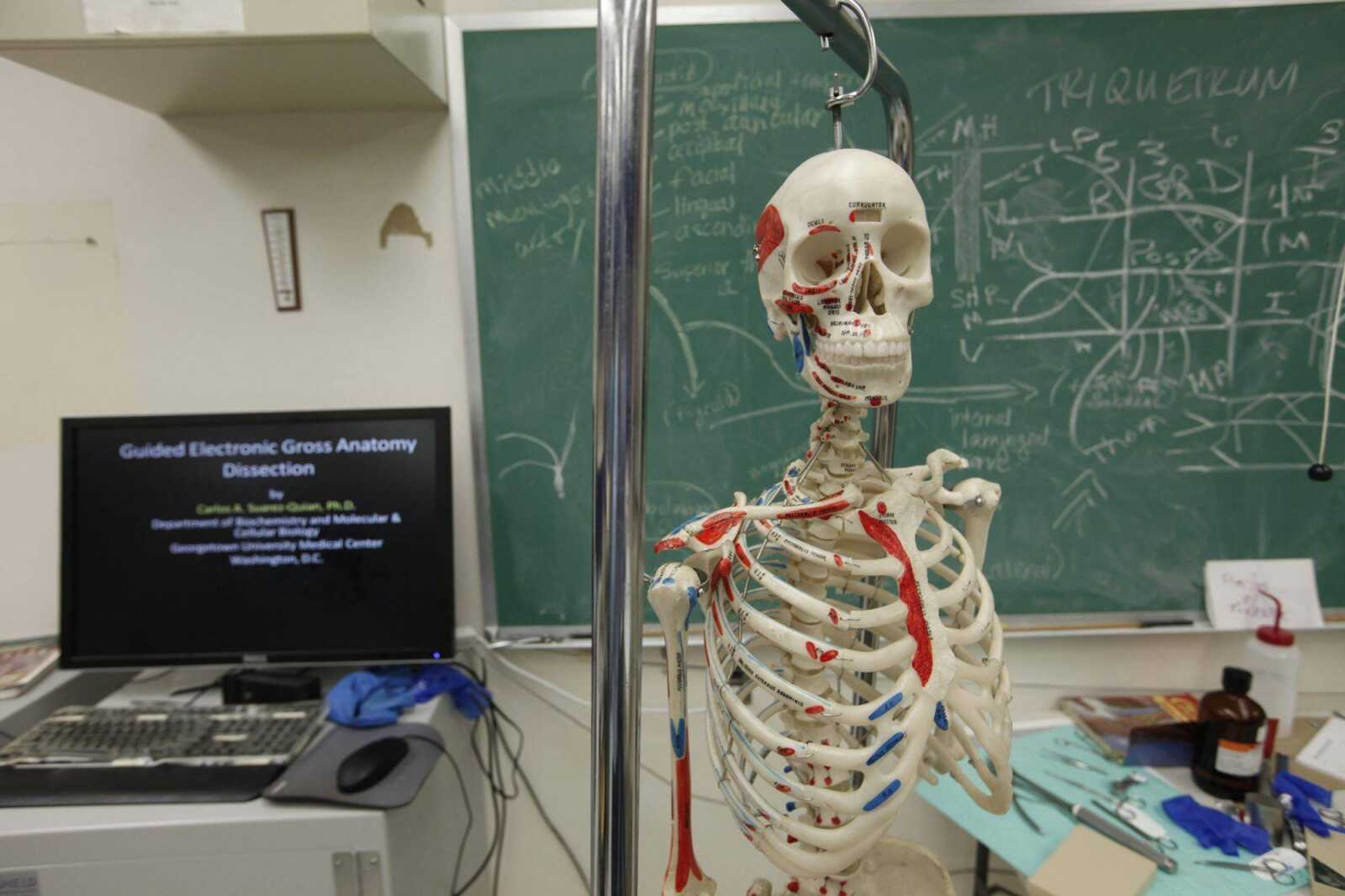

"You will be working with somebody's grandmother, father or wife," Dr. Carlos Suarez-Quian tells his 200 students before they unzip those body bags for the first time.

They're beginning a balancing act: How to steel their emotions so they can help people, without losing their compassion.

Dissecting cadavers is an evolving tradition. Sophisticated simulators and the plastic-infused organs of museum exhibits can't replace seeing and touching and lifting real bodies. In fact, demand is growing for whole-body donations.

What's changing is how they're used. Nearly one-third of medical schools have begun integrating nuts-and-bolts anatomy with clinical training spaced throughout their first year. That means Georgetown students dissect the heart, for example, the same week they begin learning how to tell the "lub-DUB" of a healthy heartbeat from the "lub-SHOOP" of a blocked valve.

"There's a very big difference between talking about chromosomes and having your knife in fat," said student Sarah Buchman of Bethesda, Md., as she eases through fat that, yes, looks like the squishy goo encountered on raw chicken.

Day 1 opens with an interdenominational prayer: "Make us grateful for these gifts these donors have given us," says the Rev. Paul McCarren as students wait silently amid the bodies.

Then Suarez-Quian has some class rules. Wear goggles when sawing bone, he warns. All the medical devices people have implanted today can mean flying bits of metal. And absolutely no photos of the bodies on Facebook or other social networking sites.

"We've been anticipating this moment a long time," said Christopher Chen of Irvine, Calif., anxious to get started. "It hits you -- wow, you're a medical student."

But unzipping the lab's 44 body bags brings a surprise, and hesitation. The cadavers aren't lying on their stomachs, ready for students to make their initial cuts on the back. They have to be flipped over. The first lesson: How stiff and heavy a dead body is, especially one filled with at least eight gallons of embalming fluid.

"I was really worried the body would fall off the table," Chen said.

Finally his team's cadaver is in position, and Chen asks to make the first cut, tracing the faintly visible spine with his scalpel.

"This skin's pretty thick. Can I have the forceps?" he asks, getting adjusted to how much force it can take to penetrate a body.

Suarez-Quian moves from table to table, showing students how to patiently peel back skin and then gently lift the triangular trapezius muscle without accidentally destroying the first nerve they'll encounter, the greater occipital nerve.

"This is not dissection by grenades. You have to go just deep enough," he says to the room.

He stops to calm a nervous student. "If you make mistakes, that's fine. Your patient's not going to complain."

"All consciousness is past. Use this body well to enhance your knowledge and lessen the pain of another," says a letter one donor wrote to the medical school.

Who donates their bodies? In some programs, women more than men. They come from every demographic. But there are no national statistics or even federal monitoring of whole-body donations, although one estimate suggests there may be 20,000 a year.

This year, Suarez-Quian got a startling phone call a few weeks before class began: The morgue was almost full. Georgetown usually receives about 60 whole-body donations annually but this year received between 80 and 90.

Schools don't pay for a body donation, but Suarez-Quian still worries that the economy may have played a role with some families perhaps deciding on donation to avoid funeral costs instead of a straightforward desire to contribute to science.

There's no evidence of a nationwide donor increase, said Dr. Richard Drake of the Cleveland Clinic, who took an informal survey for the American Association of Anatomists. About half of anatomy programs require that donors themselves, not their surviving relatives, make the decision.

The demand is growing with an increase in medical school enrollment, plus additional programs that use cadavers to allow surgeons, paramedics and other health providers to learn and practice new procedures.

Whole-body donors usually are past retirement age, and because of disease or age can't offer their organs for transplant into someone else. One impediment is weight. Georgetown has quit accepting bodies that weigh more than about 200 pounds. Just last month, the university's embalmer injured his back preparing a heavy cadaver.

Back in the lab, "My hands are getting numb already, " Nicholas Bonazza of Pittsburgh murmurs to his classmates, about 20 minutes into the day's dissection.

Embalming fluid is seeping through his surgical gloves. The skin sensation will wear off, reassures Suarez-Quian, but they must wash out their eyes quickly if any splashes.

Bonazza once worked at a funeral home, so "I've seen them," he said of bodies, "but cutting is a very different experience."

Then there's the pungent odor of phenol, a key chemical for long-term preservation. The smell can stimulate saliva, surprising students with feelings of hunger they find inappropriate.

"I couldn't eat meat for a good month or two" after a brief introductory anatomy course over the summer, Buchman said.

Starting on the anonymous back actually eases many students' nerves. A few days later, the bodies are flipped again to start working on the chest. Pretty soon, one team finds hard, irregular breast tissue in an elderly woman. Breast cancer, a student exclaims, although it will take a look under the microscope to be sure.

With bodies age 50 to 93, they'll stumble upon a variety of disease.

"If you don't believe me that smoking causes cancer, trust me, you'll see the evidence here," Suarez-Quian promises the class.

He reminds students to look beyond body structure and not forget "the humanity of anatomy."

Buchman gets the message. "You're going to be working with vulnerable people. There's nothing more vulnerable than a dead body."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.