Voters with disabilities often overlooked in voting battles

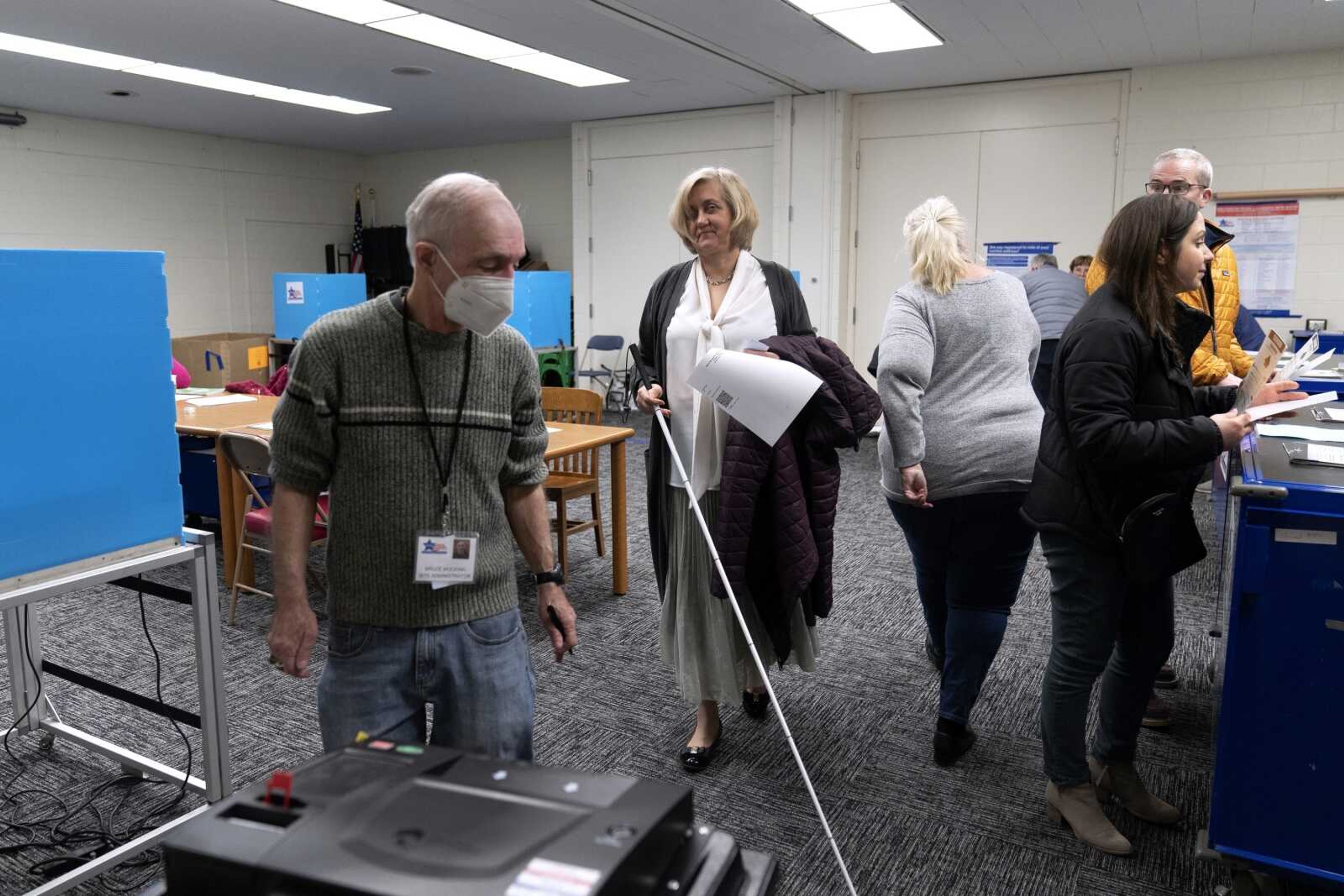

WASHINGTON -- Patti Chang walked into her polling place in Chicago earlier this year, anxious about how poll workers would treat her, especially as a voter who is blind. Even though she was accompanied by her husband, she said she was ignored until a poll worker grabbed her cane and pulled her toward a voting booth...

WASHINGTON -- Patti Chang walked into her polling place in Chicago earlier this year, anxious about how poll workers would treat her, especially as a voter who is blind. Even though she was accompanied by her husband, she said she was ignored until a poll worker grabbed her cane and pulled her toward a voting booth.

Like many voters with disabilities, Chang faces barriers at the polls most voters never even consider -- missing ramps or door knobs, for example. The lack of help or empathy from some poll workers just adds to the burden for people with disabilities.

"It doesn't help you want to be in there if you're going to encounter those kinds of low expectations," said Chang, 59. "So why should I go vote if I'm going to have to fight with the poll workers? I'm an adult and I should be able to vote without that."

Chang had a better experience when she cast an early ballot in March in the runoff election for Chicago mayor, a race that will be decided Tuesday, even as access to the ballot box remains a challenge across the city for voters like her.

Chicago is among numerous voting jurisdictions across the United States with poor access to polling locations for disabled voters. Since 2016, the Department of Justice has entered into more than three dozen settlements or agreements to force better access in cities and counties under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Many of those places are holding elections this year.

The department's targets are almost certainly an undercount of the number of places with poor access, according to disability rights activists who attempt to track ADA compliance and complaints from voters.

Several, including Chicago, either missed their deadlines without making all the requested changes or asked for an extension.

Chicago's agreement with the federal government started in 2017 but has been extended twice; the current deadline is November 2024, the next presidential election. As of February, the city had 302 polling places that complied fully with the ADA and 327 with low accessibility or none at all for disabled voters.

The expense of bringing aging buildings up to code is one challenge in complying, said Max Bever, a spokesperson for the city's board of elections. Some polling places could be forced to close.

"Things can be identified and surveyed, we can know the status of certain buildings -- but actually making and funding the appropriate changes can be a long and difficult process," he said.

People with disabilities make up about one-fourth of the U.S. adult population, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They have been ensnared in battles over access to the polls as many Republican-led states have passed restrictive voting laws in recent years, including over limits on what assistance a voter can receive and whether someone else can return a voter's mailed ballot.

In Wisconsin, disability rights activists scored a victory when they filed a legal challenge in federal court after the state Supreme Court, with a conservative majority, ruled that only the voter can return an absentee ballot. The federal court said that ran afoul of the Voting Rights Act. Nevertheless, voters with disabilities have been complaining that the federal law is being ignored in the run-up to Wisconsin's high-stakes election Tuesday, when control of the state's high court could flip.

They say local election officials throughout Wisconsin have been giving incorrect information on websites, in mailings and at polling places saying voters can't receive help or have someone else return their ballot -- without making the distinction that such assistance is allowed for voters with disabilities.

Disability must be considered a fundamental right to enhance accessibility throughout the country, said Herbert Humphrey, the ADA coordinator for Jackson, Mississippi.

"Typically, when you hear civil rights, you think about race. But no, civil rights includes the disability community, as well," he said.

Disjointed coordination between election authorities and disability advocates has been a persistent problem in Mississippi, especially related to reliable transportation. It was the reason Lee Cole, who is blind, missed a local election in Jackson in January.

That frustrated Cole, 74, because she said she tries to vote in every election.

"I live in senior housing now and we can't always vote because we can't get to the site, and that's unfortunate," she said.

Mississippi's local and state officials haven't been receptive or collaborative, said Greta Kemp Martin, litigation director for Disability Rights Mississippi.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Martin said the group met with Mississippi Secretary of State Michael Watson to discuss accessibility issues statewide. But Martin said Watson seemed uninterested, except when asking if the group had reached out to the election commission.

"His attorneys were helpful, but we received no follow-up from them about the issues that we outlined," Martin said.

Watson's office said in a statement that it has communicated its efforts to the organization to best assist voters with disabilities in Mississippi and welcomes further dialogue for future elections.

"Ensuring ADA compliance in localized polling places lies with each county, and the Mississippi Secretary of State's Office does not have enforcement authority," the statement said. "Whether the designated polling places are county-owned or privately-owned, the counties are responsible for ensuring the polling places they have selected are ADA compliant."

After conducting routine polling place surveys, Disability Rights Mississippi sent letters in 2021 to state election commissioners and Watson's office about access problems in two small towns, but said it did not receive a response. The letters said the group had found "egregious violations of the ADA."

Local election offices are often burdened with a lengthy list of responsibilities, such as ensuring that equipment works properly and defending against cyberattacks. Because of that workload, disability right advocates say they try to reach out and help ensure that polling places are accessible, said Michelle Bishop, the voter access and engagement manager at the National Disability Rights Network.

"This is a significant investment and I know that elections officials are typically under-resourced to do a multitude of things," she said.

The COVID-19 pandemic also shifted focus from ADA compliance as election offices had to ensure polling places were safe and had to mail and process a flood of mailed ballots, Bishop said.

Poll worker training is a priority, especially to make sure workers and volunteers are sensitive to the needs of disabled voters, said Denise Avant, first vice president of the National Federation of the Blind of Illinois. The group offered to make a presentation during a poll worker class following last year's midterm elections, but the Chicago Board of Elections declined, she said.

The board did let the federation assist in testing voting machines for compliance and to provide guidance on how precinct workers could interact with voters who are blind or have low vision. It expects to work with the organization in the future now that in-person training has returned.

Such training is needed to help poll workers gain a better understanding of how to best help voters with disabilities, said Kelly Knoop, who lives in Louisville, Kentucky, and has cerebral palsy. She uses a machine for those who may not be able to communicate with their own voices.

Knoop's older sister, Karen Heil, also helps her communicate and said workers at their local precinct still seem unfamiliar with their lone accessible voting machine. Jefferson County, home to Louisville, entered into an ADA agreement with the Justice Department in 2022.

"I sadly just have to say there are so many Americans that are looked upon as not being full citizens and not being worthy of all the rights that we do have," said Knopp, 56. "We just need our lives to be as important as many other minorities."

Associated Press coverage of race and voting receives support from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.