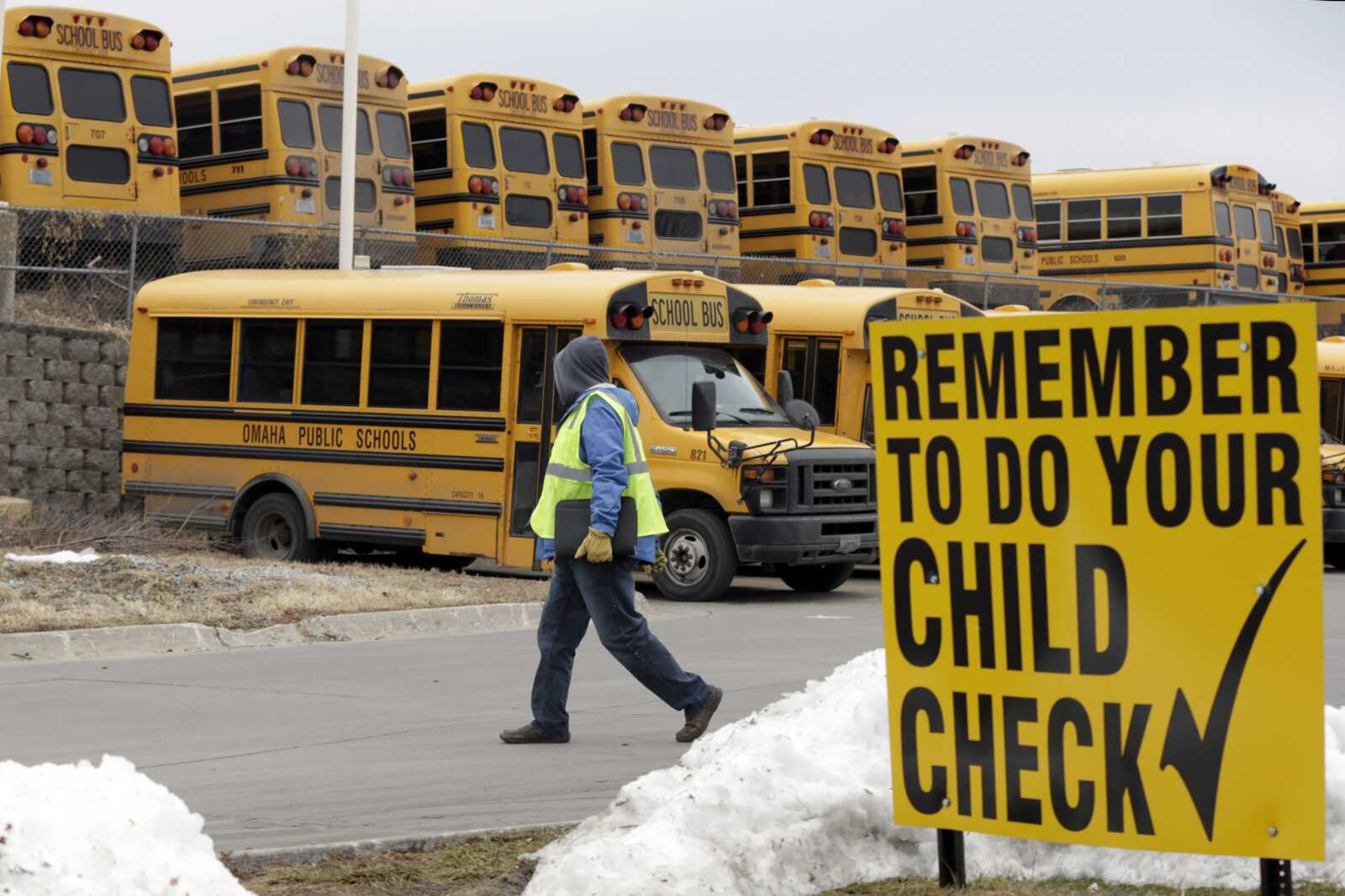

School bus driver shortage creates headaches for districts

LINCOLN, Neb. -- School districts throughout the U.S. are struggling to find school bus drivers, a challenge that has worsened with low unemployment and a strong economy. The problem has become so severe some districts are offering sign-up bonuses for new drivers, while others rely on mechanics, custodians and other school employees to fill the gap. For parents and students, the shortage can mean longer waits for a ride to school and more crowded buses...

LINCOLN, Neb. -- School districts throughout the U.S. are struggling to find school bus drivers, a challenge that has worsened with low unemployment and a strong economy.

The problem has become so severe some districts are offering sign-up bonuses for new drivers, while others rely on mechanics, custodians and other school employees to fill the gap. For parents and students, the shortage can mean longer waits for a ride to school and more crowded buses.

The shortage stems from a variety of factors, including limited work hours and high barriers to entry. Drivers generally need a commercial driver's license, which requires training, sometimes without pay, said Mike Martin, executive director of the National Association of Pupil Transportation.

"Unless you have something to fill in the gaps (between drives), you can't make the money you need to support your family," Martin said. "These days, most people are looking for some kind of regular, full-time hours."

In Iowa's Southeast Polk Community School District, transportation director Daniel Schultz said the persistent shortage has grown worse in the suburban Des Moines district because there aren't as many retired farmers, a group that commonly took the job for extra income. Now, the district relies on 51 drivers -- mostly retirees and stay-at-home parents -- to transport roughly 3,400 students to and from school each day.

Even with administrators and bus mechanics filling in, the shortage has also resulted in fewer routes, more children waiting at each stop, and crowded buses. The district needs to hire six to eight more drivers, Schultz said.

"We have to do double duty," Schultz said. "Right now, I'm driving and doing my regular job. The mechanics are driving and doing their regular jobs -- so, instead of having eight hours a day, I only get them for four. It's like pulling a teacher out of the classroom for half a day and still expecting the same job to get done."

Pay starts at $19.10 an hour, followed by a $2-an-hour raise after six months, Schultz said, but the district struggles to fill open jobs. Schultz said he's now considering a "monthly rodeo" where potential drivers could test-drive a bus in a school parking lot.

"We're just trying anything we can right now," he said.

In St. Paul, Minnesota, some students are arriving late to school because fill-in drivers aren't familiar with the normal routes. A school district in Ypsilanti, Michigan, had to cancel a day of school in February because there weren't enough substitute drivers to cover for sick drivers.

And in Hawaii last year, a driver shortage in Maui forced state officials to suspend bus rides for some students and limit rides for some others. The district offered free monthly bus passes on local public transportation.

In Lincoln, Nebraska, some positions remain unfilled even after the local school district offered $1,000 signing bonuses for new hires and a guaranteed six-hour day for all drivers. Officials also recruited an Omaha-based contractor to provide extra drivers when needed to help transport roughly 4,000 students a day. The district faced a shortage of 32 drivers this year but has reduced it to eight, transportation director Ryan Robley said.

Kristi Meyers, a Lincoln Public Schools bus driver of six years, said she loves her job and knows every student by name, but wouldn't have been able to stay without the guaranteed hours and retirement benefits offered to senior drivers. Meyers drives routes throughout the day for elementary-age children and older youths who are in a job-skills training program. In the summer, she drives a bus carrying farm workers to make ends meet.

"It's a good job, and these are great kids," she said.

But Meyers said the job is considered part-time work, which prevents drivers from collecting unemployment benefits if they get laid off or getting paid holidays.

Martin, of the National Association of Pupil Transportation, said many districts require split morning and afternoon shifts for their drivers, which some consider a hassle. Keeping an eye on noisy children while facing away from them can be difficult as well, he said.

"It really takes a special type of personality" to deal with the issues, Martin said. "Many people just don't have a burning desire to face those aspects of the job."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.