Quest to stay young may come with a price

LAS VEGAS -- It's one of those photos that make you do a double-take. Dr. Jeffry Life stands in jeans, his shirt off. His face is that of a distinguished-looking grandpa; his head is balding, and what hair is there is white. But his 69-year-old body looks like it belongs to a muscle-bound 30-year-old...

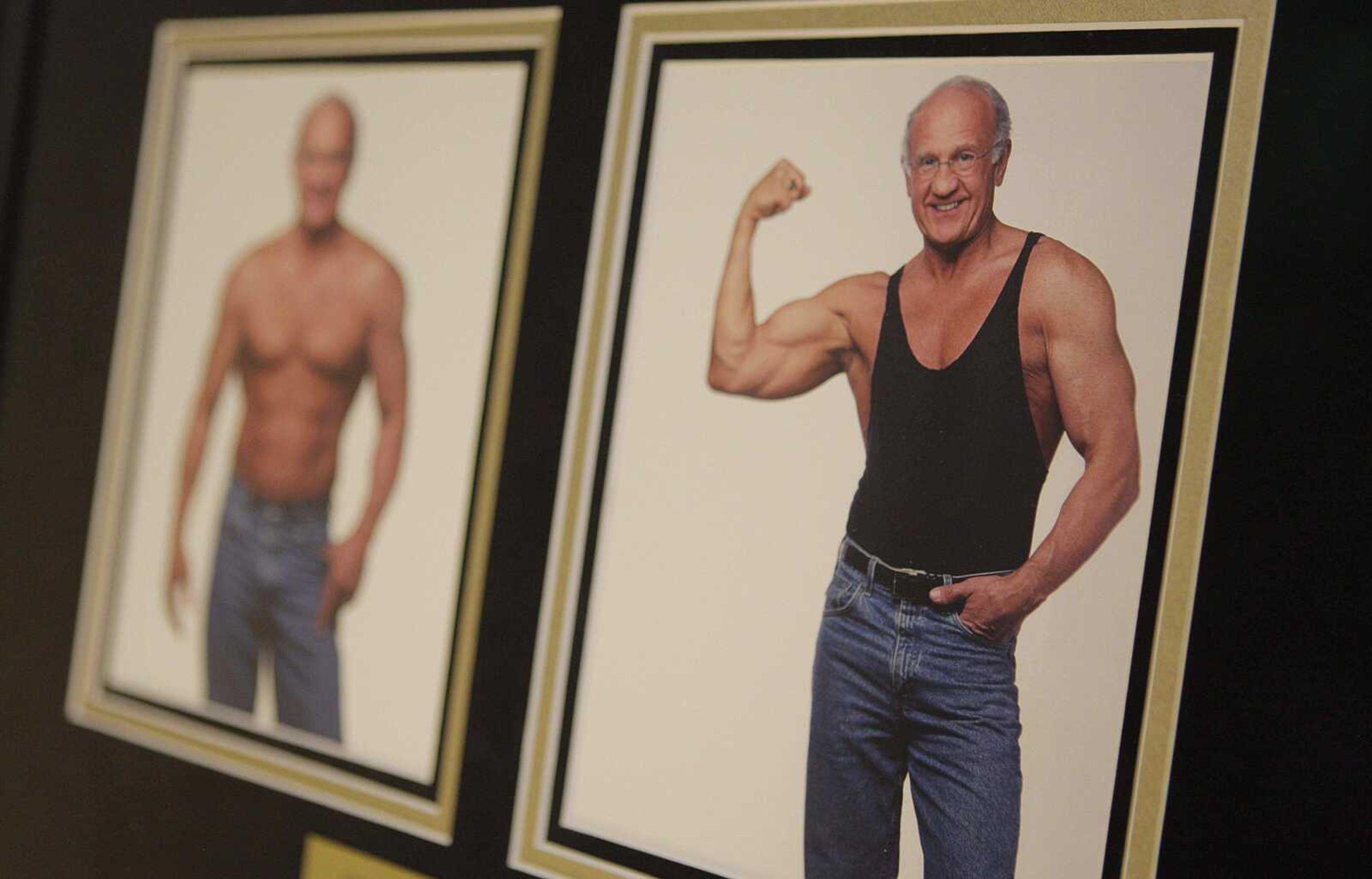

LAS VEGAS -- It's one of those photos that make you do a double-take.

Dr. Jeffry Life stands in jeans, his shirt off. His face is that of a distinguished-looking grandpa; his head is balding, and what hair is there is white.

But his 69-year-old body looks like it belongs to a muscle-bound 30-year-old.

The photo regularly runs in ads for the Cenegenics Medical Institute, a Las Vegas-based clinic that specializes in "age management," a growing field in a society obsessed with staying young.

It is becoming more common for people strive to look and feel decades younger -- to prove they are healthier and more vital than their parents were at the same age. We've all heard it: 60 is the new 50, the new 40 and so on.

As the baby boomers march toward retirement, Botox, wrinkle fillers and hormones of various kinds have become big business. Medco's latest drug trend report shows, for instance, that human growth hormone use grew almost 6 percent in 2007.

There is, of course, much to be said for taking good care of yourself. Eating healthy and exercising your body and your brain regularly are considered tried-and-true tactics for staying young. Protecting yourself from harmful sun rays is another.

But that's generally where the consensus ends.

Many in mainstream medicine and elsewhere worry that we're becoming too focused on treatments with short-term benefits that have potentially dangerous side effects and scant, if any, evidence that they'll help in the long run.

"There's a large industry of people trying to sell to people what doesn't yet exist and they're making gobs of money doing it -- much to the dismay of those of us who are vigilant about protecting public health," said S. Jay Olshansky, a public health professor and longevity researcher at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

There also are concerns that this obsession is sending the wrong message to younger generations.

Surveys from cosmetic surgery trade groups suggest that sizable numbers of people, even in their 20s, are getting cosmetic procedures. And a fall 2007 survey from TRU, a research firm that specializes in the teenage demographic, found that a quarter of people 12 to 19 -- and a third of girls in that age group -- are interested in having cosmetic surgery to improve their appearance.

However, as they age, many baby boomers are far more concerned with feeling younger, and extending their lives.

So while it is illegal for human growth hormone and other hormones to be dispensed for anti-aging purposes, Life's patient Detwiler spends more than $1,000 a month to take relatively low doses prescribed for "hormone deficiency." The idea is to bring his levels back up to those of a young man in his 20s.

"My friends say, 'Oh, Ed's on steroids,"' Detwiler says. "No, I'm not. ... I'm on hormone therapy."

He holds out his arms to indicate that his body is fit-looking, but not monstrous.

Besides human growth hormone, testosterone, and an adrenal hormone known as DHEA, his diet now largely consists of things like hard-boiled eggs, fruits, nuts, Greek yogurt, salads and palm-sized pieces of fish, chicken or low-fat beef. He also exercises regularly, alternating between intense cardio workouts and weight-resistance training.

"I can't tell you in words how great I feel," says the man who used to crack open a Pepsi to get him through the day.

For a group known as the Calorie Restriction Society, youthfulness isn't found in hormones. It's reducing food intake to, in some cases, near-starvation levels.

But the claims are much the same -- "lots of energy" and feeling "sharp," says Brian Delaney, a 45-year-old California-born writer now living in Sweden. He's president of the group that claims about 2,000 members worldwide and many more followers who use the method in hopes of markedly increasing their longevity.

By cutting daily calories to about 1,900, roughly half the recommended amount for someone his height and age, and exercising every day, Delaney has shrunk himself to about 140 pounds. He says his blood pressure, cholesterol and blood sugar levels have improved dramatically.

At 5 foot 11, he admits he's "scrawny," which he calls the main drawback.

He says he eats sensibly, replacing junk food with lots of fruits and vegetables, no meat, and two meals daily -- no lunch. Breakfast is often "a hearty bowl" of granola, with fruit, nuts and soy milk; while dinner could be fish, rice, beans, a large salad and red wine.

Other than "tons of fine wrinkles" he blames on too much sun as a child, Delaney says in most respects, "I look much younger" than 45.

It is a bragging right many strive for. But youthfulness also is seen as a means of survival in the business world, says Renee Young, a 48-year-old public relations executive in New Rochelle, N.Y.

"It feels like you're put out to pasture. No one wants to feel that how they look means that their ability to do anything is decreased," she says.

In the back of her mind is the fact that her own mother died when she was only 56.

So five or six mornings a week, even when she'd rather pull the covers over her head, Young gets up and spends two hours at the gym.

That's more than double the hour or so a day generally recommended for optimal health. And still, for her, that wasn't enough. She recently spent nearly $20,000 on a tummy tuck, which she says has inspired her to take better care of herself overall.

Using a cosmetic procedure as a motivator is worthwhile, and lucrative, to say the least, says Dr. Jonathan Lippitz. He's an emergency room physician in suburban Chicago who does cosmetic procedures, such as Botox and skin fillers, in a separate practice.

But it's also a "very slippery slope," with patients sometimes willing to take more risk than they should and some doctors who'll accommodate.

"We all say, 'I want my hair different. I want my eyes different,"' Lippitz says. "This idea of being perfect is a problem, though, because it's not reality.

"I have people coming in and saying 'I want these lips.' I say, 'You can't have these lips.'

"I say, 'We'll work with what you have."'

For those going to even greater lengths to try to keep aging -- and ultimately death -- at bay, there also are no guarantees.

Calorie restriction guru Dr. Roy Walford succumbed to complications from Lou Gehrig's disease at age 79, closer to the average than the "extraordinarily long life" his followers talk about on their website.

Meanwhile, Dr. Alan Mintz, founder of Cenegenics, died at the relatively young age of 69 due to complications during a brain biopsy.

Some research has suggested that human growth hormone injections can cause cancer. They've also been linked with nerve pain, elevated cholesterol and increased risks for diabetes.

Even so, Life, now the chief medical officer at Cenegenics, remains steadfast. Among other things, he points to studies that suggest that human growth hormone in low doses poses no cancer risk, if there is no preexisting cancer.

"Within the next 10 years, maybe less, this is going to be thought of as mainstream medicine -- preventing disease, slowing the aging process down, preventing people from losing their ability to take care of themselves when they get older and ending up in nursing homes," Life says.

Detwiler is betting on that.

"People might ask, 'Hey, what's happened to these people? Was it cutting edge? Or did it cut it short?"' he says, as he walks into a gym for another workout.

"I think only time will tell."

------

On the Net:

Cenegenics: http://www.cenegenics.com

Calorie Restriction Society: http://www.calorierestriction.org

------

Martha Irvine is an AP national writer. Lindsey Tanner is an AP medical writer. They can be reached via mirvine(at)ap.org or http://myspace.com/irvineap

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.