Professor offers insight on Frederick Douglass

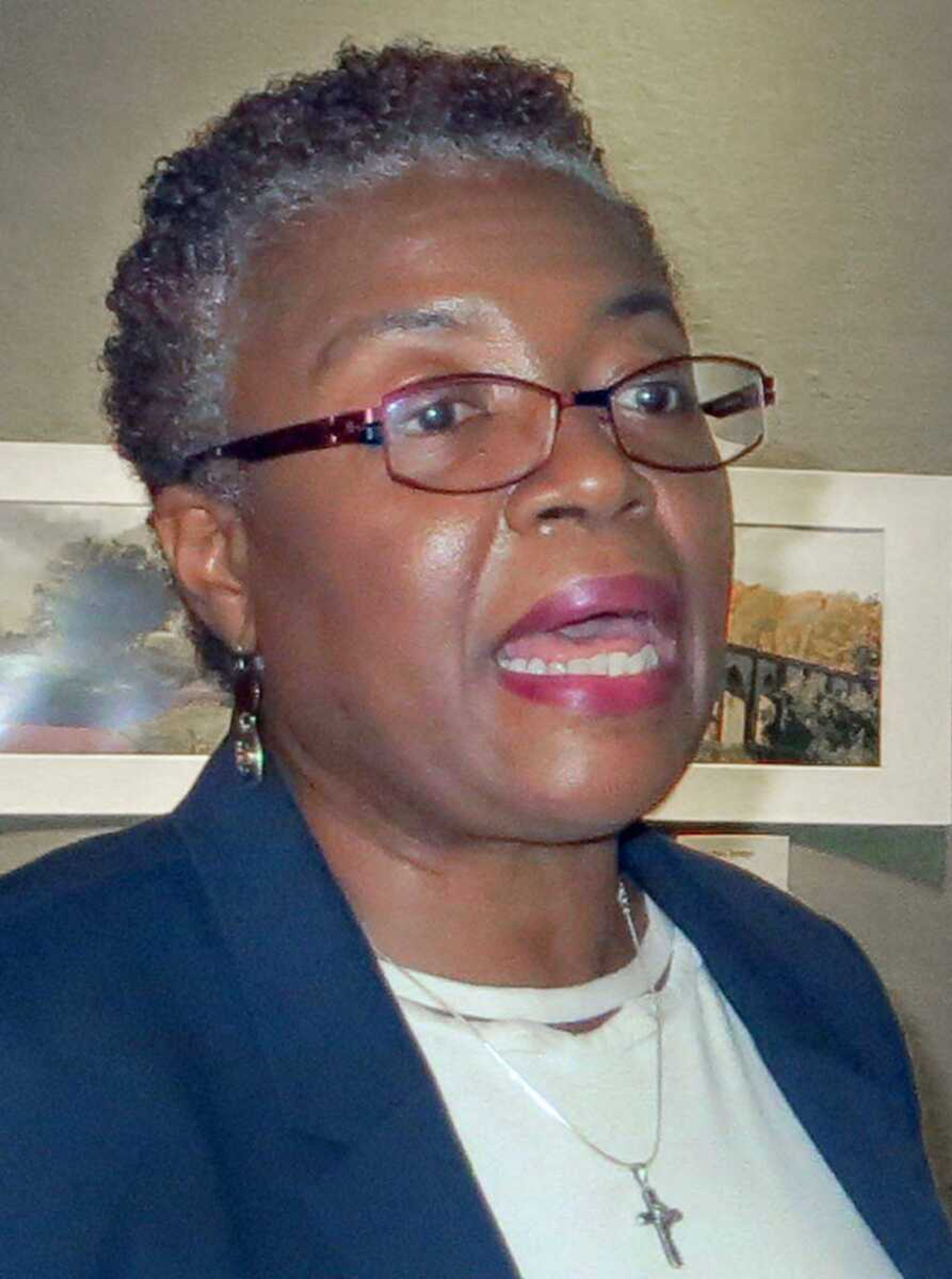

Before he was revered as a significant figure in civil rights history, Frederick Douglass was a bit of a rabble rouser, Dr. Debra Foster Greene, professor of American History at Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Mo., told an audience at the Cape Girardeau Public Library on Sunday...

Before he was revered as a significant figure in civil rights history, Frederick Douglass was a bit of a rabble rouser, Dr. Debra Foster Greene, professor of American History at Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Mo., told an audience at the Cape Girardeau Public Library on Sunday.

Greene's presentation, "The Life of Frederick Douglass," was given before an audience of 49 in the library's Geraldine Hirsch Community Room. After showing a video about Douglass' life, Greene offered insights on his political activities, writings and associations.

In the late 20th century, Greene said, Douglass was often classified among the four major figures in black history -- Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Harriett Tubman and Rosa Parks, all of whom were "sanitized for middle school consumers."

"What is often omitted is the fact that each of these people, before they became role models and leaders, were viewed in their time as irritants, agitators and incendiary in some small or large way," Greene said.

Douglass was born a slave in February 1818 in Talbot County, Md. He was sent to live with Hugh Auld's family in Baltimore in 1826, and hired out as a field hand for a year to "slave breaker" Edward Covey, according to information from the library. On Sept. 3, 1838, Douglass escaped to New York City and settled in New Bedford, Mass.

Douglass came to abolition under the mentorship of William Lloyd Garrison, Greene said, who advocated a brand of abolition that involved no voting and civil disobedience. Garrison, she said, saw the Constitution as a "proslavery document."

Just more than six months into his life as a free man, but a fugitive slave, Douglass read an issue of Garrison's anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator. After that, Douglass found his community. Douglass attended a talk when Garrison visited New Bedford in 1838 and traveled with local abolitionists to an anti-slavery conference in Nantucket, Mass., where he gave his first public address sharing the story of his life in slavery. That same year, he married Anna Murray Douglass.

After the conference, Douglass was offered a position as an agent for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. However, he was still a fugitive, and under the Constitution at the time, a slave could not run away to another state.

During this phase of his career, Douglass published his first autobiography, "The Narrative Life of Frederick Douglas, An American Slave," which was translated into French and German. By 1848, three years after it appeared, 11,000 copies were out in the U.S. and it was in its ninth edition in England.

As part of his anti-slavery career, Greene said, Douglass visited Great Britain and Ireland several times. Understanding his celebrity put his life in danger, Douglass' English friends collected more than $710, and through an intermediary, purchased Douglass' freedom.

Douglass published the first issue of his weekly newspaper, North Star, from Rochester, N.Y., in 1847, and, following the Harpers Ferry raid, led by John Brown, Douglass fled to Britain for safety. Greene said Douglass was believed to be involved in planning the event.

During 1860 and 1861, Douglass was convinced the solution to black hopelessness was rebellion, Greene said. But he was heartened by the Civil War, seeing it as a holy war for black freedom, Greene said. In early 1863, he led the recruitment of black troops for the Union Army. He told President Abraham Lincoln he couldn't win without black men, but at the time, black men were mistreated in both the armies of the north and south and not paid the same as whites.

Because of this, Douglass quit recruiting and started agitating, Greene said. He went to Washington, D.C., in August 1863 to talk to Lincoln about soldier pay, promotions and treatment of black prisoners. He also served as an orator and fundraiser for Freedmen Aid societies, becoming president of the Freedman's Saving Bank in Washington in 1872.

In 1884, he married Helen Pitts, who was white, and Greene said Douglass realized he had stepped over a social boundary that whites and blacks didn't like. However, they remained married until Douglass' death Feb. 20, 1895, in Washington.

Several of those who attended appreciated Greene's vast knowledge of Douglass.

"I thought it was excellent," Charmagne Schneider of Cape Girardeau said of the presentation. "I've read the autobiography of Frederick Douglass, but it's been a long time. I thought she did a really good job of bringing [in] other historical facts that were going on at the time, like the Civil War."

Denise Lincoln, also of Cape Girardeau, said the chance to hear Greene speak was something that "we've not had much of" here.

" ... The pivotal history of the Civil War is so important to who we are today," Lincoln said. "I think Douglass has an important part to play, so I'm glad it was more than just a surface examination of the history."

Dr. Loretta Prater said the presentation was "excellent."

" ... I was drawing so many parallels to history down through the years, and even to today, in terms of the struggles," Prater said.

rcampbell@semissourian.com

388-3639

Pertinent address:

711 N. Clark St., Cape Girardeau, Mo.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.