New stroke treatment can vacuum clots out of the brain

WASHINGTON -- It's a tiny vacuum cleaner for the brain: A new treatment for stroke victims promises to suction out clogged arteries in hopes of stopping the brain attack before it does permanent harm. Called Penumbra, the newly approved device is the latest in a series of inside-the-artery attempts to boost recovery from stroke, the nation's No. 3 killer...

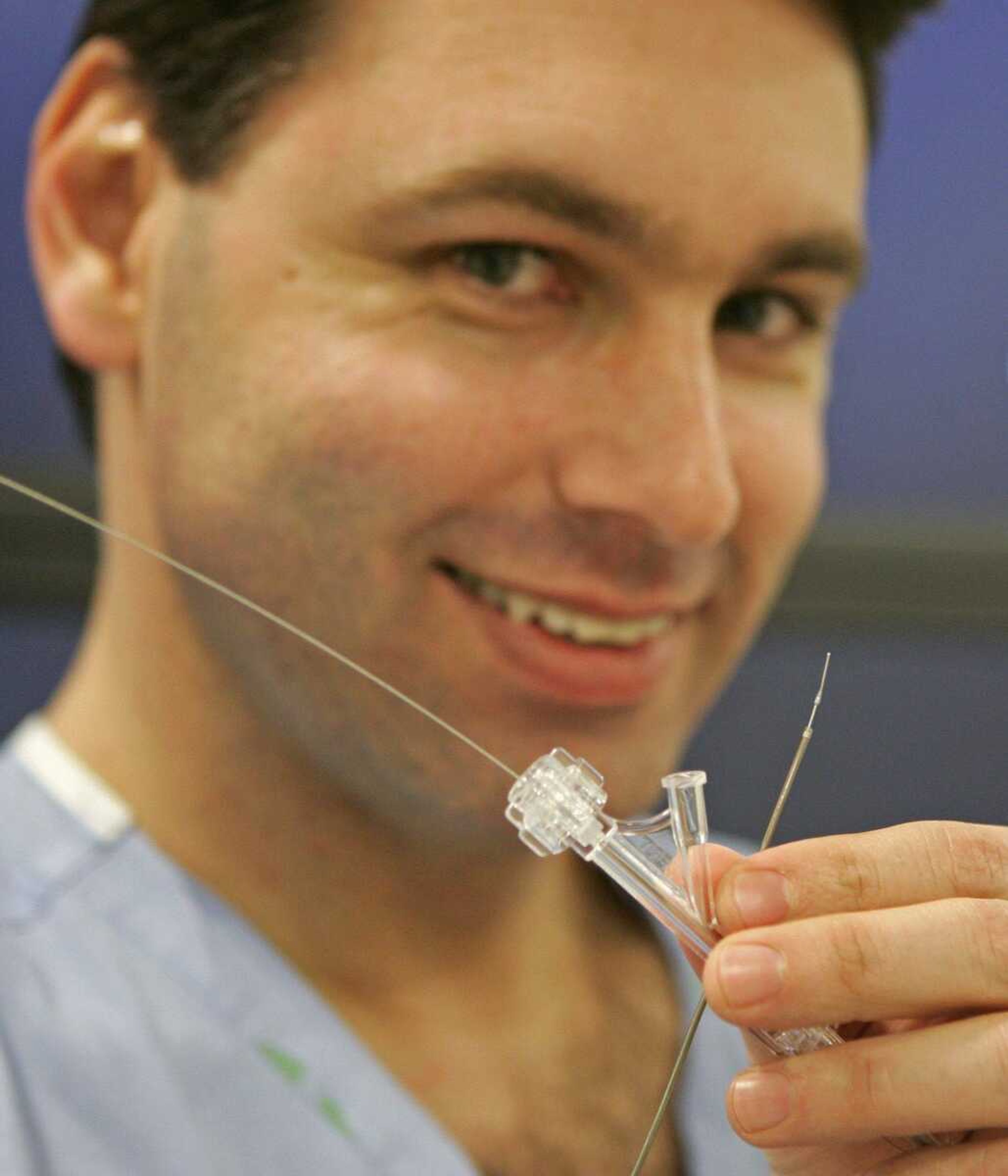

WASHINGTON -- It's a tiny vacuum cleaner for the brain: A new treatment for stroke victims promises to suction out clogged arteries in hopes of stopping the brain attack before it does permanent harm.

Called Penumbra, the newly approved device is the latest in a series of inside-the-artery attempts to boost recovery from stroke, the nation's No. 3 killer.

More than 700,000 Americans suffer a stroke each year, and more than 150,000 of them die. Survivors often face serious disability.

Most strokes occur when blood vessels feeding the brain become blocked, starving delicate brain cells of oxygen until they die. For those, the clot-busting drug TPA can mean the difference between permanent brain injury or recovery -- but only if patients receive intravenous TPA within three hours of the first symptoms.

Yet fewer than 5 percent of stroke sufferers get TPA because they don't get specialized care in time. And of those treated, it only helps about 30 percent, because the clot is often too big or tough for TPA to bust.

Enter Penumbra, an option for patients who miss out on early care or if standard TPA treatment fails.

Specialists thread a tiny tube inside a blood vessel at the groin and push it up the body and into the brain until it reaches the clog. Just like a vacuum cleaner, it sucks up the clot bit by bit to restore blood flow.

However, unclogging sometimes does more harm than good in severe strokes, said Dr. Walter Koroshetz , deputy director of NIH's National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

When the dam is broken and blood rushes into oxygen-deprived brain tissue, it sometimes triggers swelling or a brain hemorrhage. Either can kill.

So treatment is a balancing act: Using brain scans to estimate if the stroke already has killed all the brain tissue it's going to, or if enough still could be salvaged that it's worth the risk of this injury, Koroshetz explained.

"Your ability to succeed with taking the clot out depends on what's going on in the brain," he cautions.

The NIH is funding a 900-patient study comparing standard therapy with different inside-the-artery treatments -- the TPA drip, ultrasound, and the Merci Retriever -- to tell if and how they should be used. Researchers will decide soon whether to include the new Penumbra device in that study.

What treatment to pick is a doctor's dilemma. For patients, the message is clear: Call 911 as soon as you experience stroke symptoms. They include sudden numbness or weakness, especially on one side; confusion, trouble speaking or walking; or an abrupt terrible headache.

Aretha Streeter didn't realize the worst headache of her life meant a stroke had begun, although her mother had died of a stroke and her sister had survived one. Fortunately she went on to her job as a hospital technician at Rush, so care was just steps away when she slumped over.

"It came and went so fast," Streeter says in amazement at both the speed of the stroke, and its treatment.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.