Libya's new charter can shoot down law

TRIPOLI, Libya -- A new law that excludes former officials of the Moammar Gadhafi era from public office is dividing Libya and deepening the turmoil plaguing the country since the 2011 civil war that ousted the erratic leader. Passed by parliament Sunday essentially at gunpoint -- heavily armed militias were parked outside government buildings and refused to leave until it was approved -- the law bans from politics not only those who held office, but clerics who glorified the dictator and researchers who worked on his notorious ideological tract, the Green Book.. ...

TRIPOLI, Libya -- A new law that excludes former officials of the Moammar Gadhafi era from public office is dividing Libya and deepening the turmoil plaguing the country since the 2011 civil war that ousted the erratic leader.

Passed by parliament Sunday essentially at gunpoint -- heavily armed militias were parked outside government buildings and refused to leave until it was approved -- the law bans from politics not only those who held office, but clerics who glorified the dictator and researchers who worked on his notorious ideological tract, the Green Book.

The measure is one more symbol of the divided society that has emerged after Gadhafi in the oil-rich North African nation, stalling its troubled transition to democracy.

The collapse of central state authority and the already weakened military under Gadhafi has left successive governments without strong and decisive law enforcement bodies and forced them to lean on militias, formed initially from rebel forces that fought Gadhafi, to fill the security vacuum.

Legal experts, as well as supporters and opponents of the new law, note that it can be overridden if it's not included in a new constitution that has yet to be drafted. The parliament itself is temporary, with its main mission being the formation of a panel to write the charter that will result in new elections.

"This parliament and this government are transitional and therefore any decrees that are passed under transitional bodies become invalid," veteran lawyer Abdullah Banoun said. "Only after the new constitution passes, and we know how Libya will look in the future, only then can parliament debate laws like that."

According to a time frame set by the transitional government during the eight-month civil war, the new constitution was supposed to have been drafted by November 2012. The process stalled amid a struggle between two factions in parliament -- a group of mostly Islamists and their rivals over formation of the Cabinet.

In the meantime, many senior politicians and former Gadhafi-era officials who defected to the rebel side may lose their posts.

Banoun supports the idea of purging Gadhafi-era officials but objects to the passage of the law under pressure from the militias, which are comprised of former rebels who have refused to lay down their arms and hold sway in the absence of a strong military or police force.

"The law in itself is a legal violation because parliament passed it while it was under a state of terrorism and intimidation," Banoun said.

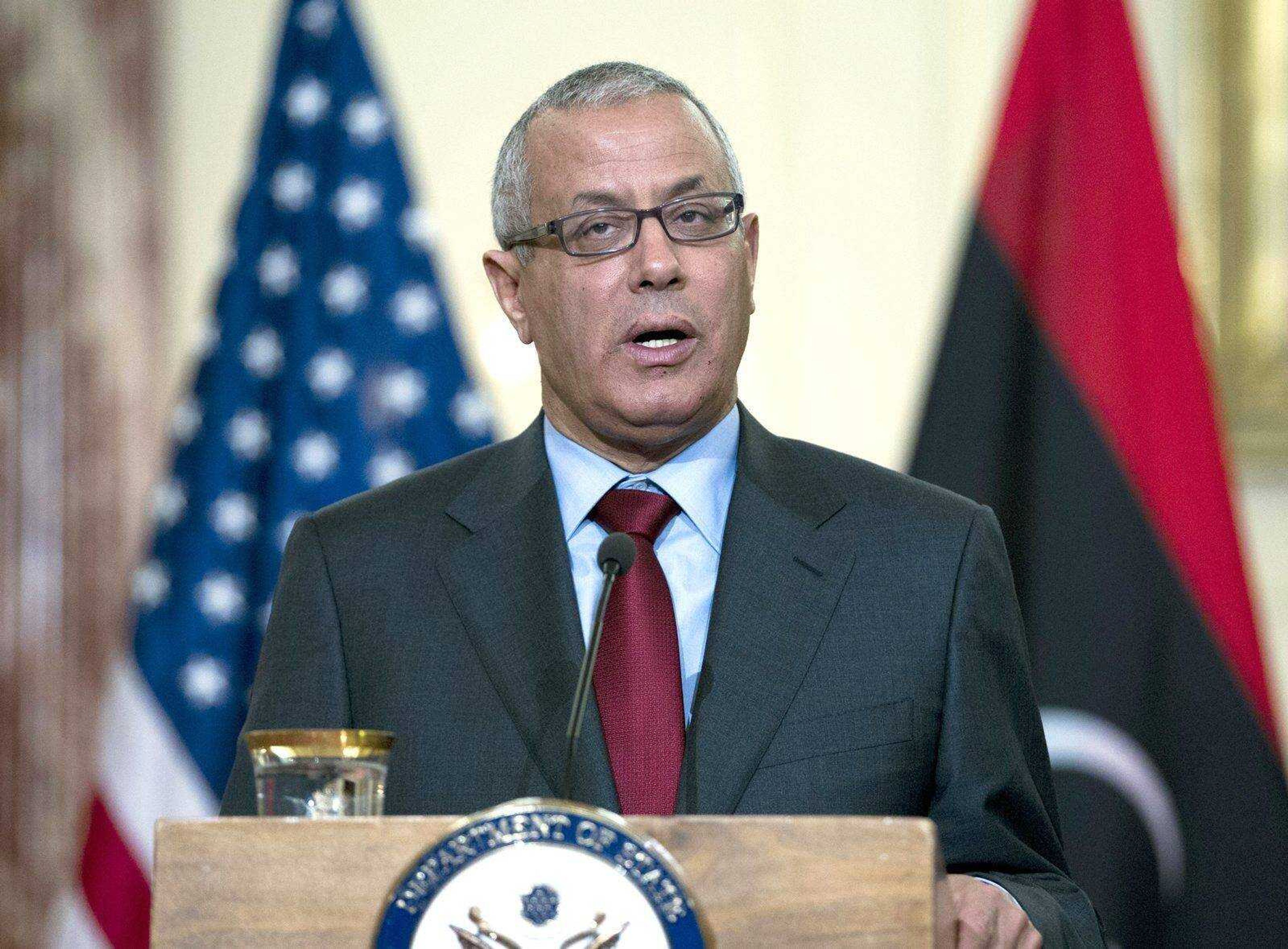

After the militia groups ended their siege of government buildings, Prime Minister Ali Zidan promised a Cabinet reshuffle and praised them Wednesday as "revolutionaries."

He said his government would look into the backgrounds of all senior officials and fire those banned by the new law.

Under the legislation, anyone with ties to the former regime would be barred for 10 years from state institutions including the military, police, judiciary, local councils, universities, financial oversight bodies or media institutions.

The law bans anyone who held a post in or "behaved" in a way that served and prolonged Gadhafi's regime.

This includes participants in the coup that overthrew Libya's monarchy in 1969, members of the notorious Revolutionary Guards that hunted down Gadhafi's opponents, legislators in the Gadhafi-era parliament, members of local councils, ambassadors, heads of student unions, those with business ties to Gadhafi family members, employees of state-run media and those who took part in failed reform efforts by Gadhafi's son and heir apparent, Seif al-Islam.

Also targeted are those who studied and researched the Green Book, which laid out Gadhafi's vision for rule by the people, but ultimately put all power in his hands alone.

Also banned are Libyans who cooperated with security agencies and violated human rights, those who glorified Gadhafi and promoted his Green Book and ultraconservative Muslim clerics and others who opposed the 2011 civil war that led to Gadhafi's capture and killing.

Supporters of the law say such sweeping measures are needed to allow state institutions to develop free of the influence and corruption that plagued the Gadhafi era.

Critics say it perpetuates the regime's practice of excluding a large bloc of Libya's more than 6 million people from political life.

Opponents have dubbed the law "de-Gadhafization," and say it is reminiscent of what happened in Iraq after the U.S.-led invasion in 2003 that ousted Saddam Hussein. Under that policy, Iraqis with ties to Saddam's ruling Baath Party lost their jobs, effectively draining the country of the most qualified and skilled bureaucrats.

The new Libyan law is to take effect in early June.

It is not clear how many people will be dismissed, but those whose jobs are on the line include Mahmoud Jibril, the liberal-leaning politician and head of the National Forces Alliance that won the largest number of parliamentary seats in the July 2012 elections.

Also affected would be parliament leader Mohammed al-Megarif, who was Libyan ambassador to India in 1980 before he joined the opposition in exile.

Al-Megarif wrote a series of books on Gadhafi's repressive policies and led the country's oldest armed opposition movement, the National Front for the Salvation of Libya, which plotted assassination attempts, including a daring 1984 raid on Bab al-Aziziyah, the late dictator's fortified compound in Tripoli. The regime cracked down on the group, executing and arresting many of its members. Many fled abroad, where they worked as political activists.

"The law is very unfair to people like al-Megarif, because it puts them on equal footing with people who killed the revolutionaries during the war," said Tawfiq Breik, of the liberal-leaning National Forces Alliance.

Majda al-Falah, a lawmaker with the Freedom and Construction Party, the political arm of the powerful Muslim Brotherhood, said parliament will discuss laws governing the election of a 60-member constitution panel next week.

She said it will be up to this panel to keep the law or remove it.

------

Michael reported from Cairo.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.