Iraqi officials work with citizens to gain cooperation in ousting al-Qaida

GUBA, Iraq -- A convoy of strangers rumbled into this quiet Sunni village on a riverbed north of Baghdad, their armored vehicles enveloping the town in a cloud of dust. Peeking out from mud brick homes, suspicious residents tried to get a glimpse at the intruders...

GUBA, Iraq -- A convoy of strangers rumbled into this quiet Sunni village on a riverbed north of Baghdad, their armored vehicles enveloping the town in a cloud of dust. Peeking out from mud brick homes, suspicious residents tried to get a glimpse at the intruders.

It was their governor -- a man this poor farming village had never seen in his nearly three years in office.

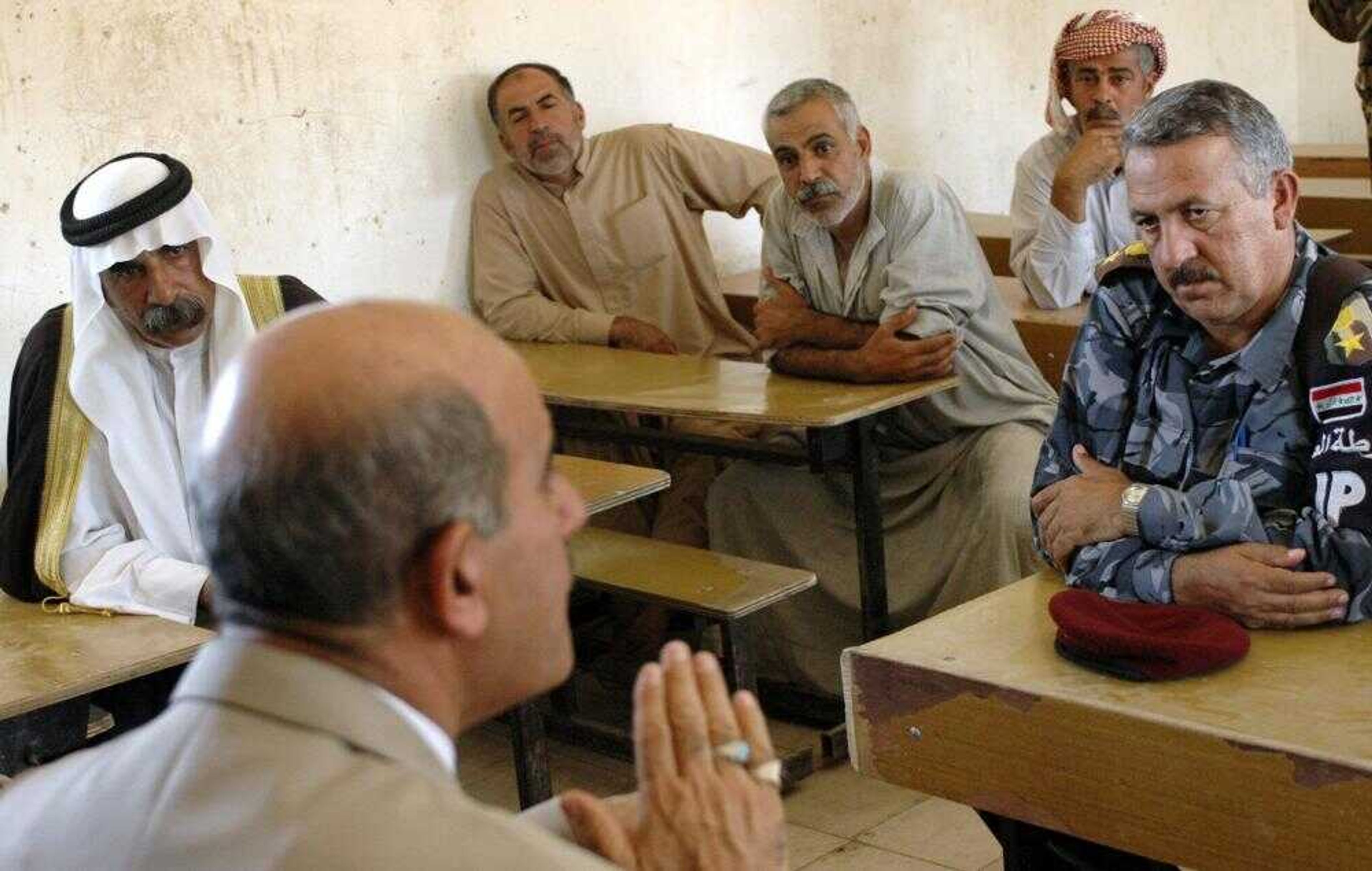

Under protection of U.S. soldiers, Gov. Raad Rashid al-Tamimi -- a Shiite -- sat atop a child's desk in a dilapidated schoolhouse early last week and goaded a dozen of Guba's tribal elders to join a reconciliation effort that has so far enticed 19 of the province's 26 major tribes.

A day later, a suicide bomber ravaged another such reconciliation meeting in al-Tamimi's hometown of Baqouba, killing at least 15 people and lightly wounding the 52-year-old governor, who was believed to be the target. Two U.S. soldiers were wounded in the bombing.

Such is the ebb and flow of reconciliation and violence in Diyala province, a battered landscape of warring tribes, fertile valleys and pockets of al-Qaida fighters. The sectarian and tribal chasms are wide here, and elected officials -- who are mostly Shiite -- cannot safely travel the province's sectarian patchwork.

"The governor wouldn't come here alone, and I wouldn't let him. This has been a very dangerous place," said Col. David Sutherland, the top U.S. commander in Diyala, who escorted al-Tamimi on his weekend tour along with about 20 U.S. soldiers.

The U.S. blames al-Qaida for exacerbating tribal fights in the province, where dozens of U.S. soldiers have died in a bid to pacify tribal conflict and chase out or kill foreign fighters linked with al-Qaida.

Still, nearly one million of Diyala's 1.6 million residents are followers of sheiks who have signed a U.S.-sponsored reconciliation agreement in recent months, U.S. military officials said.

But policing the pledge is difficult, and U.S. officials acknowledge that some sheiks may renounce violence in front of U.S. commanders, but succumb to sectarian pressure afterward.

In the reconciliation agreement, leaders swear on the Quran to support the elected Iraqi government and to refuse to allow al-Qaida and other militant groups safe haven in their tribes. Thirteen of the 19 tribes involved are Sunni; six are Shiite.

In Diyala, the challenge is not only to get Sunnis to deny al-Qaida refuge in their ranks. It is also to unite Sunni and Shiite factions that have fought generations-long battles that were made worse by the U.S.-led war and influx of foreign fighters.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.