Columbia man honored for his work in conservation

COLUMBIA, Mo. -- Some years ago, Glenn Chambers got down on his hands and knees and crawled into a dusty crevice to find exactly what he'd been looking for: his pet coyote giving birth to a litter of six pups. He slid up next to the mother, flicked his 135-mm lens up to his eye, threw it in focus and hit the shutter, hoping his canine friend wouldn't mind. She looked up for a minute, he said, and went back to cleaning her puppies. The photos Chambers shot were breathtaking...

COLUMBIA, Mo. -- Some years ago, Glenn Chambers got down on his hands and knees and crawled into a dusty crevice to find exactly what he'd been looking for: his pet coyote giving birth to a litter of six pups.

He slid up next to the mother, flicked his 135-mm lens up to his eye, threw it in focus and hit the shutter, hoping his canine friend wouldn't mind. She looked up for a minute, he said, and went back to cleaning her puppies. The photos Chambers shot were breathtaking.

"That was my trademark," he said. "Get close, use a smaller lens and get super, super sharp pictures. It turned out all right."

That's what Chambers, 78, has done all his life -- from growing up on a farm in rural Missouri hunting ducks and game with his father to Emmy-winning works of wildlife cinema in his later years.

"Wherever I went, I carried a camera with me and I took pictures of whatever," he said.

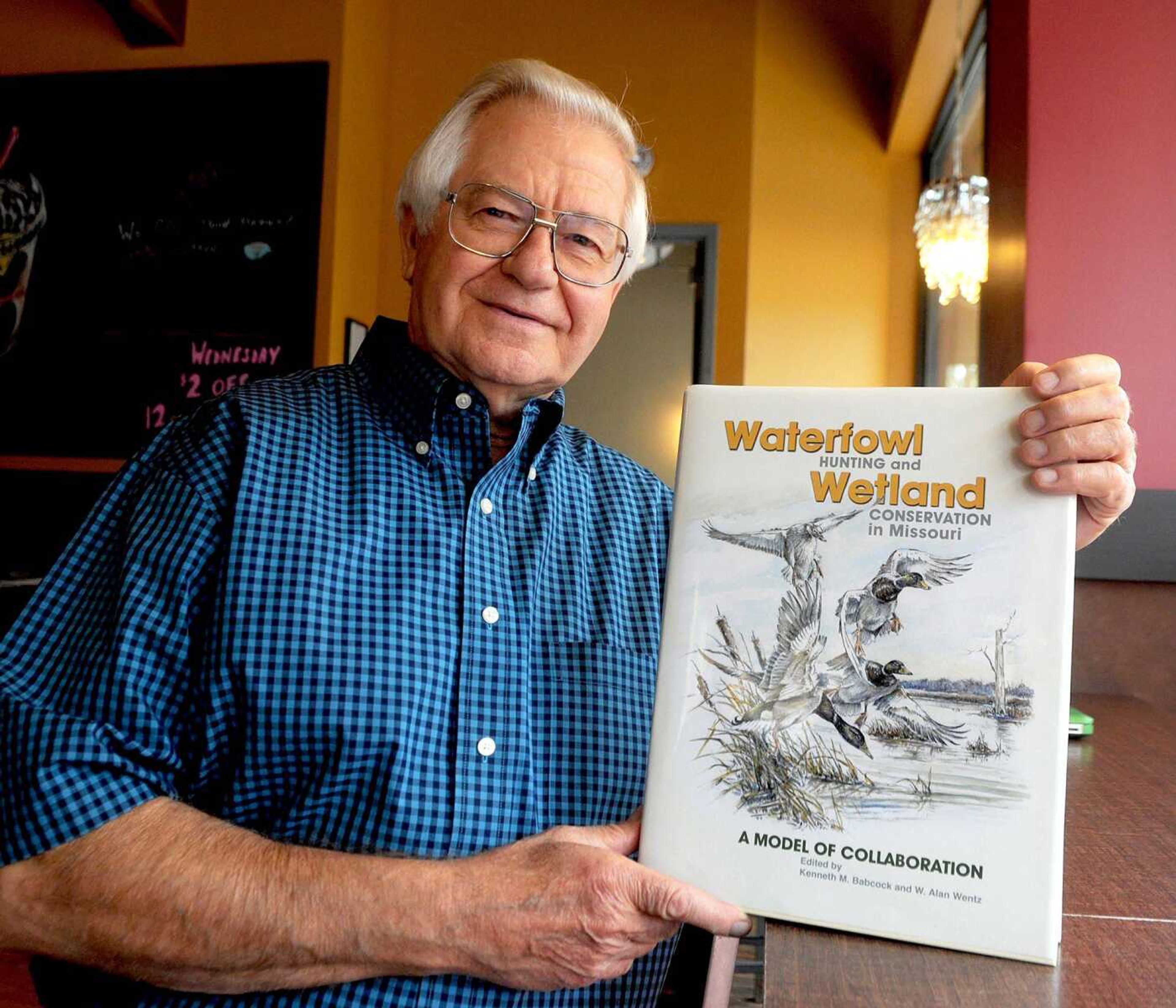

The Boy Scouts of America recently gave Chambers, of Columbia, its 40th William T. Hornaday Gold Medal, a lifetime achievement award for environmental conservation. Chambers is the first Missourian to receive the honor.

"We call it the Olympic medal bestowed by Earth," said John Fabsits, assistant scout executive for the Great Rivers Council. "If you look over Glenn's lifetime of what he's done for conservation, he's always been there."

Chambers' career in conservation spans more than half a century, ranging from duties as a civil servant to an Emmy-winning wildlife cinematographer. He's held 26 different species of wild animals in captivity -- otters, coyotes, ravens and rattlesnakes, to name a few -- and raised them to be released into the wild. He parlayed his award-winning still photography into drawings, paintings and sculpture.

"If I take an animal and imprint it to myself, I become a surrogate parent to them," he said. "They'll behave generally as they do in the wild and I can photograph them and show them to the public. The end result is a tremendous view into their way of life."

That perspective is what the Scouts hold dear when choosing award recipients, Fabsits said. It takes a lifetime to cultivate that kind of understanding and appreciation for wildlife.

Early start

"Oftentimes we don't know or don't understand the things that happen when we influence an animal in an ecosystem," said friend and former colleague at the Missouri Department of Conservation Tom Russell. "I think his understanding started as a young boy on the farm. He and his dad hunted and he grew up with animals and around animals."

Chambers was born and raised in Adrian, Missouri, a town of about 1,600 people according to 2010 census figures, an hour south of Kansas City. He went to school in a one-room schoolhouse, he said, and he sat next to the class library -- a bookshelf. The first book to catch his eye was John James Audubon's "Birds of America."

"The kids would go out and play at recess, but I'd hurry back in to see that bird book," he said. "My roots were put down in a farming community and that connected me with the outdoors."

Chambers went to Central Missouri State University on an engineering scholarship, but ditched the program to focus on science and environmental studies after a year, he said. He got a job with the Missouri Department of Conservation out of college and moved to Columbia after a promotion. He worked on a master's degree at the same time.

Midway through his career, Chambers changed paths, turning from research to photography and videography. He spent two years profiling the return of wild turkeys to Missouri in a documentary film, then adopted six wild river otters and toured the country with his wife, Jeannie, to promote habitat restoration.

National Geographic turned Chambers' travels into a movie, "Otter Chaos." The otters met more than 1 million people in 80,000 miles of traveling, he said.

"As much has Glenn has been on the road with the otters and wherever he's been, he knows every small town restaurant," said Fabsits. "He knows where all the good fried catfish is in the state of Missouri."

When Chambers retired in 1995, relaxation wasn't quite in the game plan, he said. He kept traveling with the otters and took photos for more publications. He counts arctic foxes, prairie chickens and waterfowl among his subjects.

He turned some of his favorite images into drawings, paintings and sculpture, too, he said, though as he ages, those projects look less and less appealing.

"I can help people understand and I can advocate for these animals if I can take pictures of them," Chambers said. "It's been a fun ride, and it all started by growing up on a farm."

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.