Freebie treasures: finding beauty and value in repurposing

AUGUSTA, Maine -- OK, I admit it. I pick up castoff gloves I find along the side of the road. You never know; these gloves that have blown out of the backs of pickup trucks can, if you're patient, be useful. You just need to hold onto that lonely left until you can match it up with a nearly matching right...

AUGUSTA, Maine -- OK, I admit it. I pick up castoff gloves I find along the side of the road.

You never know; these gloves that have blown out of the backs of pickup trucks can, if you're patient, be useful. You just need to hold onto that lonely left until you can match it up with a nearly matching right.

Sometimes you get lucky and find a pair straight off, which makes for a very satisfying day.

My freebie treasures are not limited to gloves. It's amazing what's out there free for the picking. I've taken junk skis and made them into a coat rack.

Once, I made a doll house for my daughter out of old chair seats and kindling wood. The shingles on the dollhouse roof were cut carefully from old plastic milk bottles (before they were collected widely for recycling).

I've grown very fond of wood from collapsed barns, a visual blight to many people but pure beauty to me. Cut into the right lengths, with corners properly angled, the barn board can be transformed into perfect picture frames. Some surround old newspaper front pages I socked away through the years (a super-bold "BUSH WINS" from December 2000 gobbles up the front page of the Bangor Daily News). Barn board forms the perimeter of a big mosaic of Maine's State House that I made from business cards amassed over three decades. (It now hangs in the State House itself.)

While workers were renovating parts of the State House in the 1980s, they tossed an old, light-shaded snack-bar counter (I think maple or birch) out into the parking lot to be hauled off to the landfill. But I got there first, and into the back of my van it went.

The bulky thing flew out of the rear hatch, into the street, on a hill, but I scrambled out and shoved it back in.

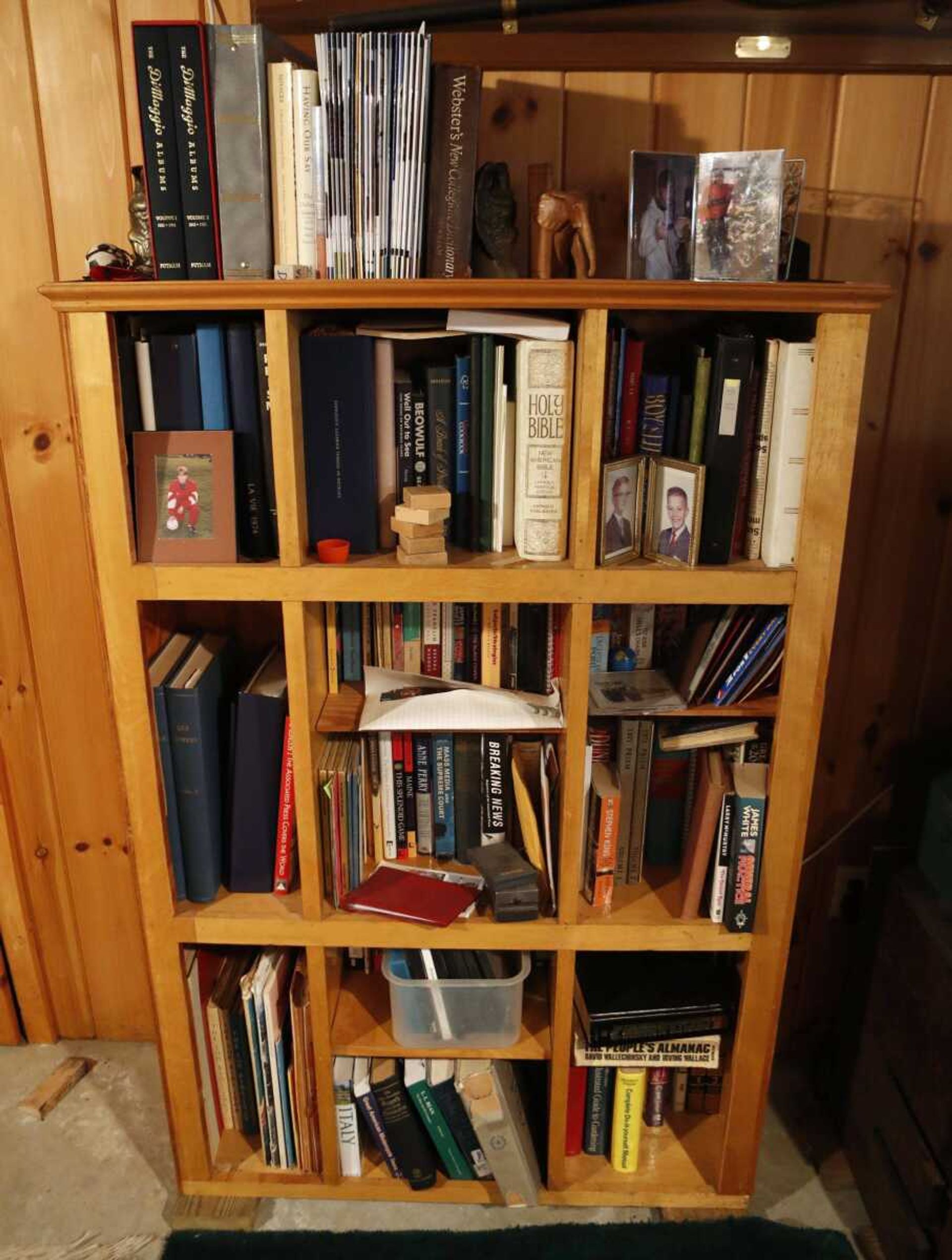

With some moderate remodeling, it has served as a solid and some might say handsome bookcase in my home for years.

I guess my masterpiece would be the bar I fashioned out of a sunken fishing boat. I eyed the 18-foot, handmade wooden boat lasciviously as it lay in the watery muck for a couple of summers.

Finally assured that it was abandoned, I floated it temporarily and towed it home with hopes of refurbishing and permanently floating it.

Given its age, that wasn't going to happen.

Armed with an all-purpose saw, I transformed the boat into three pieces, fashioning two of them into a bar and the bow into a back bar with shelves for glasses, mugs and so on.

The hemlock bar top (repurposed scrap from another household project) served well for a few years. Then, just a couple of years ago, the state had the old, worn copper removed from the Maine State House dome and decided to sell the scrap to artisans and schmoes like me.

Newly buffed copper from the dome now graces the top of our bar. Fill your steins to dear old Maine!

The propensity to save and reuse old or castoff stuff is well ingrained in the Maine psyche, where Yankee thrift is more or less a given.

I once did a story on a Mainer who set a new standard by re-repurposing the huge wooden crate that housed Charles Lindbergh's Spirit of St. Louis on its return trip to the United States after his historic flight to France.

For a while, the 290-square-foot crate served as a bungalow in Hopkinton, New Hampshire.

Then Larry Ross of Canaan, Maine, bought it and turned it into a museum to house Lindbergh memorabilia.

Lobster traps that have been repurposed into coffee tables are everywhere (including my den). But the urge to coax new lives out of our worn, tired and rejected stuff is not limited to Mainers.

The Junk Gypsies have made a career of it. From their Texas-based design studio, sisters Amy and Jolie Sikes search out useful junk and transform it into attractive pieces for the homes of their clients, who include country-music stars and Hollywood actors.

You can see it on their TV show or in their new book, "Junk Gypsy: Designing a Life at the Crossroads of Wonder and Wander" (Touchstone).

My fixation with the used but not useless started a long time ago.

As a kid in New Jersey in the early 1960s, I was helping my father as he remodeled what had been a dilapidated carriage stable into a proper garage to house our Corvair and Chevy Nomad.

To say I helped is a bit of a stretch, because I mostly stood, watched and waited for a command to hold a piece of wood or, if I was lucky, hammer in a few nails.

At one point, I noticed he was running old pieces of wood through his table saw to be used for the sheathing.

I asked why he wasn't using new wood.

Peering at me over his glasses, he said in a most serious tone, "Why, son, this is perfectly good wood."

Then he directed me to take the hammer and straighten out some of the old, slightly bent nails he had been pulling from the lumber as he dismantled the building.

By then, I understood what he was talking about. I got pretty good at straightening out old, rescued nails.

Years later, in my own house, he would chide me if he saw me using "bent nails." But I still use them whenever I can. And I use his same old table saw to cut planks -- usually used ones.

The saw neatly chewed its way through 7/8-inch oak planks from a tree on our lot that we had to have cut down. I had the trunk milled and planed and dried it for a couple of years, producing beautiful, solid planks. They are now the cabinets in our cottage's kitchen and a porch swing that hangs from our backyard rock maple tree.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.