Finding your ancestor – Part II

Find your immigrant ancestors with expert tips on finding passenger lists, naturalization records, and more. This guide covers key resources and strategies to trace your family's journey to America.

Passenger lists exist in multiple locations. The “old standby” source is the series by P. William Filby and others, “Passenger and Immigration Lists Index,” with volumes beginning in 1982. Services such as Internet Archive (www.archive.org) have digitized some, or they are on Ancestry with search capability. This series was a compilation of published lists, keyed to the original source for each name. Another classic source is the three-volume “Pennsylvania German Pioneers,” by Ralph B. Strassburger, edited by William J. Hinke. If you have 18th Century or early 19th Century German immigrant ancestors, these volumes are passenger lists and lists of those taking the oath of allegiance.

Digitized microfilms of many original passenger lists are on subscription services such as Ancestry. Examples include records from the ports of New York, New Orleans, Boston, Philadelphia and other entry points. Ancestry offers a focused search feature on “Immigration and Travel” under the search option. If you suspect a family member came in through Ellis Island (1892-1954), visit the web site: heritage.statueofliberty.org/. You must create an account to access all the features. Because some immigrants traveled back to the home country for visits, another potential source is passports. Many are searchable on FamilySearch and have the bonus of a photograph of the traveler.

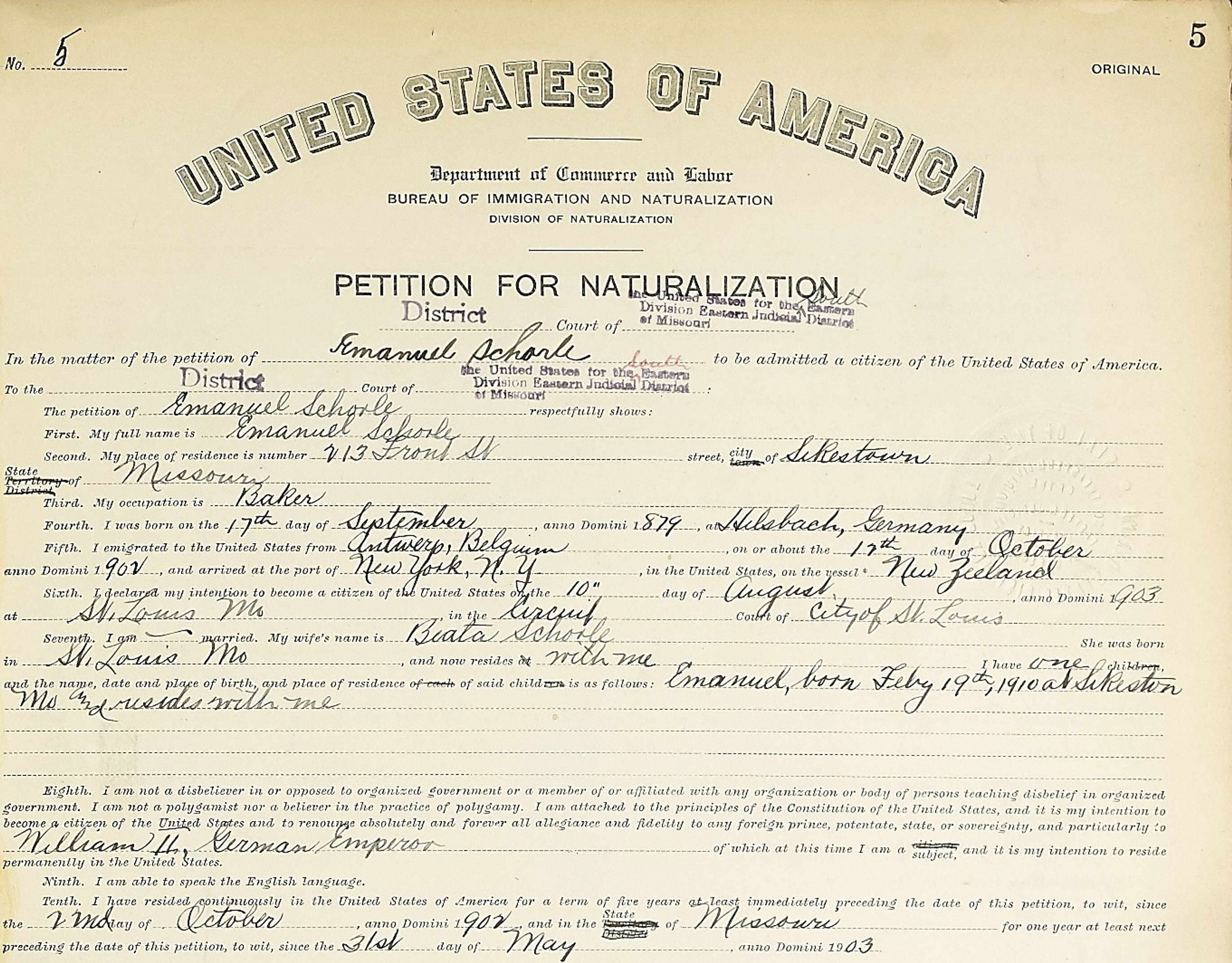

Naturalization is the process by which an immigrant, born outside the U.S. of non-citizen parents, becomes a U.S. citizen. African Americans became citizens with ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868. Native Americans became citizens in 1924 when the Indian Citizenship Act became law. In some cases, declarations of intent to become a citizen and naturalization records are in different courts. In general, look in county records prior to 1906, and federal court records thereafter.

The process in 1790 took one court visit, required a two-year residency and was open to free, white aliens only. Children of naturalized citizens became citizens. The law changed in 1798, mandating two court visits and a period of five years between declaring intent to become a citizen and naturalization. A change in 1824 specified alien minors became citizens at age 21, and in 1855 alien wives of those naturalized also became citizens. An 1862 law sought to encourage enlistment in the Union Army by granting automatic citizenship to aliens who enlisted and earned an honorable discharge.

There are numerous sources for determining an immigrant’s place of origin. You may find it necessary to check multiple sources to locate the information, and then it still may prove elusive. Family histories, databases, local histories and biographies and genealogical compendia often compile this information. (An example of a compendium are books by Henry Z. Jones on the origins of 18th-century German immigrants.) Local genealogical, historical or ethnic societies may have information on the origin of local families or individuals. Unfortunately, many of these groups are disappearing as membership declines. Most such groups do have periodicals, and you can often review contents using the Periodical Source Index (PERSI – www.genealogycenter.info/persi/).

Documents in archival collections in archives or libraries include place of origin in some cases. Federal censuses for 1850 and thereafter list the birthplace of those enumerated. However, depending on the whim of the census-taker, locations may be general (e.g., Germany) or more specific (e.g., Baden). Original records such as vital, church, cemetery, military service and pension, Social Security and Homestead application files are other places to look. Finally, check obituaries and other newspaper articles for your ancestor to locate place of origin.

Indentured servitude, when immigrants worked for a time to pay their passage to the new country, generated records, although these may no longer exist. Look in church registers, court records, deeds, servant contracts, journals and other personal narratives, land patents, merchant account books, newspapers, passenger lists or probate records.

Do not overlook foreign sources for information about your ancestor. Look in sources equivalent to those of the country of arrival, such as emigration lists and property sales. If you are “stuck” consider hiring a foreign researcher or expert on the country of origin. Common sources of information on emigrants include letters of manumission or permits to emigrate (required in many monarchies), letters of recommendation from officials or clergy, shipping company records and port of departure lists.

In seeking records of your immigrant ancestor, consider that libraries and online subscription services are highly valued for immigration research – perhaps more than any other aspect of genealogy. Spelling of surnames may vary in these records, so try ALL possible spellings. Finally, learn more about your ancestor by reading social history books about their ethnic group and place of origin for insight into their immigration experience.

Bill Eddleman, Ph.D. Oklahoma State University, is a native of Cape Girardeau County who has conducted genealogical research for over 25 years.

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.