Alton E. Parks: Band leader and dog racer

The Roaring 1920s wooed young folks with new music, new fashions and daring social freedoms. Meanwhile, Cape Girardeau's white church folks heard wary sermons and college students were prohibited from music's natural companion -- dancing feet. Amid those culture clashes, 15-year-old Alton E. Parks perfected his embouchure, coaxing jazzy riffs from his cornet, playing in his school orchestra, and dreaming of directing his own dance band...

The Roaring 1920s wooed young folks with new music, new fashions and daring social freedoms. Meanwhile, Cape Girardeau's white church folks heard wary sermons and college students were prohibited from music's natural companion -- dancing feet. Amid those culture clashes, 15-year-old Alton E. Parks perfected his embouchure, coaxing jazzy riffs from his cornet, playing in his school orchestra, and dreaming of directing his own dance band.

Cape Girardeau's sonic landscape of live-performed music was strong in the Black community. Music was performed at home, at church, at the courthouse park and at school. Alton, the son of Second Baptist Church pastor, the Rev. Paul Parks, and choir director/pianist mother Ellen A. (nee Jones) Parks, was raised amidst aunts, uncles and cousins who were performing musicians at church, in concert bands and noted community events.

Alton was 6 when his father died, and 10 when his mother remarried, moving the family to Allenville. The rural setting offered little in the way of comprehensive education or music, which may explain why, in 1920, Alton and his sisters lived in Cape with his grandmother, Amanda Jones, and aunts. Lincoln School provided a better educational curriculum, including an orchestra and band which regularly entertained appreciative crowds.

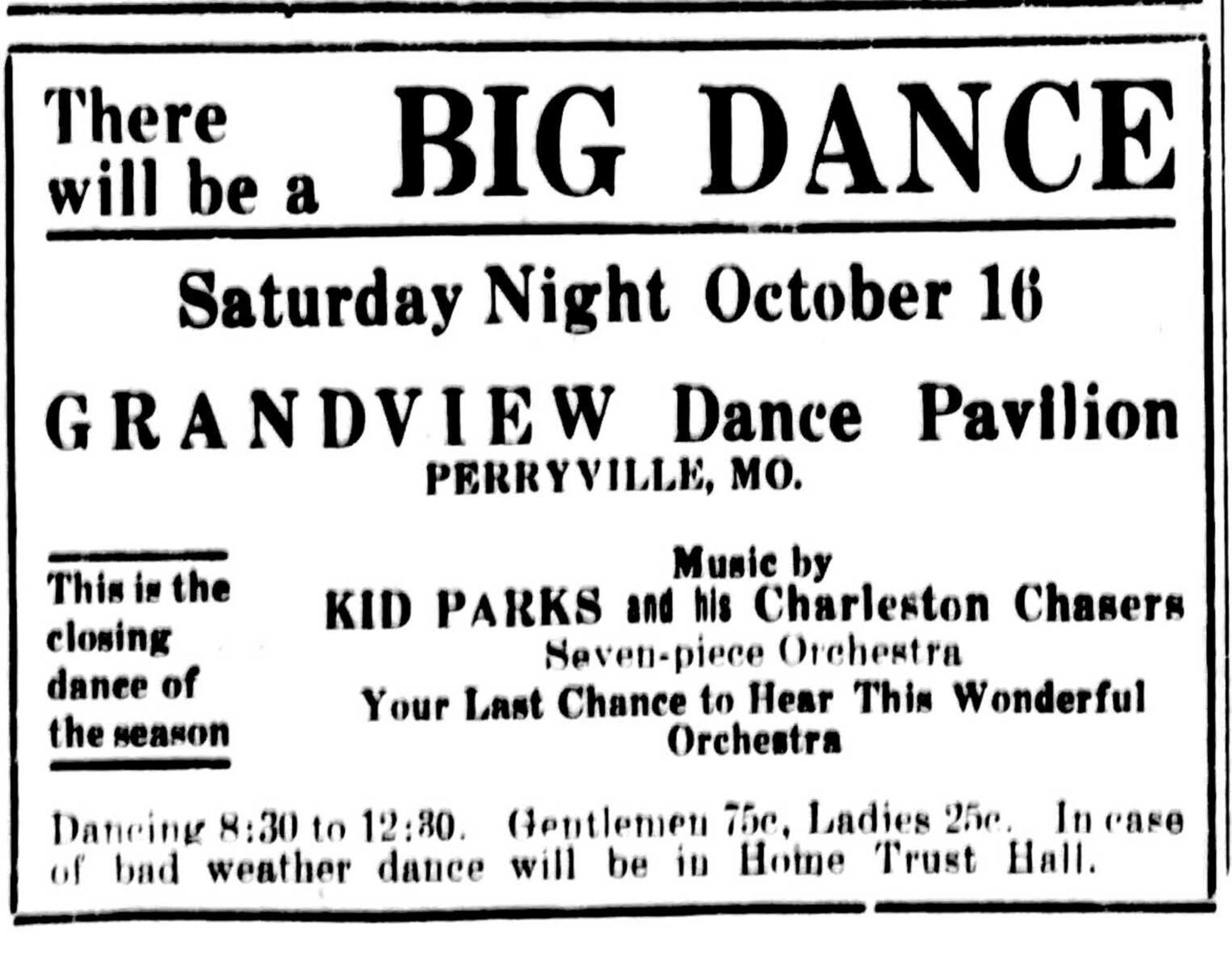

Alton left home at age 17, to travel with "an amusement organization." He returned to Cape in 1925, inspired to form his own orchestra -- "Kid Parks and his Charleston Chasers." They played dance venues at Jackson's Circle Theater, Cape's "Cocoa Cola Hall," Poplar Bluff, Missouri, and at Perryville, Missouri's Grandview Dance Pavilion (white) in 1926. The next year, they were invited to give a broadcast program on Cape's radio station, gigs in Fornfel, and Masonic gatherings at Fairgrounds Park.

Newly named John S. Cobb High School sponsored a farewell party for Alton in early 1928, as he departed for Cairo, Illinois, to join Roberson's Syncopators band. Years of bands and venues took Parks to Terre Haute, in 1930, and to San Diego by 1935, where he played at the College Inn by night and barbered at the naval station by day.

In March 1954, nationally renowned Ebony Magazine featured a five-page article about Parks. Surprisingly, his career as a bandleader was not the article's focus, but Parks' second successful endeavor, as a greyhound dog racer in California and Mexico.

World War II nearly silenced bands of the era. In those idle, downbeat years, Parks met a breeder who introduced him to the world of dog racing. Starting as a kennel keeper, trainer, then owner, by the 1950s Parks became the only Black licensed to race his kennel on major U.S. tracks.

Ebony's photos depict scenes at the track, kennels and at home. Parks seems a happy, contented man, respectful of his dogs, and grateful for his opportunities. One photo features Parks, dapper in his straw-skimmer hat, playing his cornet for his prized winning dog "Fonnie O'Day."

Loved for his humor and larger-than-life energy, his nieces and nephews still revel in Ebony Magazine's attention to their uncle.

To view the Ebony Magazine article about Alton Parks, go to archive.org/details/sim_ebony_1954-03_9_5/page/96/mode/2up?q=%22Alton+Parks%22

Connect with the Southeast Missourian Newsroom:

For corrections to this story or other insights for the editor, click here. To submit a letter to the editor, click here. To learn about the Southeast Missourian’s AI Policy, click here.