More to explore

-

-

-

Local News 4/16/24New Cape Girardeau City Council members sworn in; multiple appointments made to advisory boardsThe Cape Girardeau City Council swore in new members and approved various appointments to multiple advisory boards Monday, April 15. New council members David Cantrell, Ward 4, and Rhett Pierce, Ward 5, took the oath of office at the meeting....

Local News 4/16/24New Cape Girardeau City Council members sworn in; multiple appointments made to advisory boardsThe Cape Girardeau City Council swore in new members and approved various appointments to multiple advisory boards Monday, April 15. New council members David Cantrell, Ward 4, and Rhett Pierce, Ward 5, took the oath of office at the meeting.... -

Local News 4/16/24Fredericktown woman arrested in Cape on charges of stealing car, possessing drugs2Anna J. Dobyns, 40, is in the custody at the Cape Girardeau County jail in lieu of a $40,000 bond on charges of first-degree tampering with a motor vehicle, possession of a controlled substance and unlawful possession of drug paraphernalia. ...

Local News 4/16/24Fredericktown woman arrested in Cape on charges of stealing car, possessing drugs2Anna J. Dobyns, 40, is in the custody at the Cape Girardeau County jail in lieu of a $40,000 bond on charges of first-degree tampering with a motor vehicle, possession of a controlled substance and unlawful possession of drug paraphernalia. ... -

Local News 4/16/24Judge awards $23.5 million to undercover St. Louis officer beaten by colleagues during protest6ST. LOUIS — A St. Louis judge Monday awarded nearly $23.5 million to a former police officer who was beaten by colleagues while working undercover during a protest. Luther Hall was badly injured in the 2017 attack during one of several protests that...

Local News 4/16/24Judge awards $23.5 million to undercover St. Louis officer beaten by colleagues during protest6ST. LOUIS — A St. Louis judge Monday awarded nearly $23.5 million to a former police officer who was beaten by colleagues while working undercover during a protest. Luther Hall was badly injured in the 2017 attack during one of several protests that... -

-

-

Local News 4/15/24Cape airport explores funding for possible new air traffic control tower11As Cape Girardeau Regional Airport’s construction projects move along, airport manager Katrina Amos and the Airport Advisory Board may start to look at possible funding options for a new air traffic control tower. Amos said the next big project on...

Local News 4/15/24Cape airport explores funding for possible new air traffic control tower11As Cape Girardeau Regional Airport’s construction projects move along, airport manager Katrina Amos and the Airport Advisory Board may start to look at possible funding options for a new air traffic control tower. Amos said the next big project on... -

Local News 4/15/24Take a hike: Charleston introduces the town’s first trail — The Byrd WalkCHARLESTON — The late James L. "Jim" Byrd III loved his hometown of Charleston. He also loved trains. Now his family has combined those two loves to continue to grow Byrd’s legacy. With funds from Byrd’s estate, a new walking path was recently...

Local News 4/15/24Take a hike: Charleston introduces the town’s first trail — The Byrd WalkCHARLESTON — The late James L. "Jim" Byrd III loved his hometown of Charleston. He also loved trains. Now his family has combined those two loves to continue to grow Byrd’s legacy. With funds from Byrd’s estate, a new walking path was recently... -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Local News 4/12/24Congress likely to kick the can on Covid-era telehealth policiesNearly two hours into a Capitol Hill hearing focused on rural health, Rep. Brad Wenstrup emphatically told the committee’s five witnesses: “Hang with us.” Federal lawmakers face a year-end deadline to solidify or scuttle an array of covid-era...

Local News 4/12/24Congress likely to kick the can on Covid-era telehealth policiesNearly two hours into a Capitol Hill hearing focused on rural health, Rep. Brad Wenstrup emphatically told the committee’s five witnesses: “Hang with us.” Federal lawmakers face a year-end deadline to solidify or scuttle an array of covid-era... -

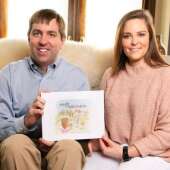

Local News 4/12/24Area students named to Mizzou '39 list1Two college students from Southeast Missouri were recently named to the Mizzou '39 list. Grace Blanton of Sikeston and Sam Varnon of Cape Girardeau were selected by the Mizzou Alumni Association and Alumni Association Student Board for this...

Local News 4/12/24Area students named to Mizzou '39 list1Two college students from Southeast Missouri were recently named to the Mizzou '39 list. Grace Blanton of Sikeston and Sam Varnon of Cape Girardeau were selected by the Mizzou Alumni Association and Alumni Association Student Board for this... -

Local News 4/12/24Notre Dame to transition to president/principal model beginning July 17Notre Dame Regional High School announced Monday, April 8, that it will be transitioning to a president/principal model Monday, July 1. Current principal Tim Garner will assume the role of president, while assistant principal Paul Unterreiner will...

Local News 4/12/24Notre Dame to transition to president/principal model beginning July 17Notre Dame Regional High School announced Monday, April 8, that it will be transitioning to a president/principal model Monday, July 1. Current principal Tim Garner will assume the role of president, while assistant principal Paul Unterreiner will... -

-

Local News 4/12/24Coroner still hasn't found attorney as Missouri AG seeks to remove him from office12More than two months after the Missouri Attorney General's Office filed court action to remove Cape Girardeau County Coroner Wavis Jordan from office, the local officeholder has still not found an attorney to help him fight to keep his job. Wavis...

Local News 4/12/24Coroner still hasn't found attorney as Missouri AG seeks to remove him from office12More than two months after the Missouri Attorney General's Office filed court action to remove Cape Girardeau County Coroner Wavis Jordan from office, the local officeholder has still not found an attorney to help him fight to keep his job. Wavis... -

Local News 4/12/24Bollinger Co. man again charged with failure to register as sex offenderA Bollinger County man has been charged for at least the fourth time for not registering as a sex offender. Bradley G. Wyss, of Marble Hill faces 10 to 30 years in prison after a Bollinger County Sheriff's deputy observed him in recent days driving...

Local News 4/12/24Bollinger Co. man again charged with failure to register as sex offenderA Bollinger County man has been charged for at least the fourth time for not registering as a sex offender. Bradley G. Wyss, of Marble Hill faces 10 to 30 years in prison after a Bollinger County Sheriff's deputy observed him in recent days driving... -

Local News 4/12/24Oesch appointed as associate circuit judge for Scott CountyJEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — Former Scott County Prosecuting Attorney Amanda L. Oesch has been appointed to serve as an associate judge for the 33rd Judicial Circuit. On Friday, April 12, Gov. Mike Parson announced judicial appointments to the 21st, 22nd,...

Local News 4/12/24Oesch appointed as associate circuit judge for Scott CountyJEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — Former Scott County Prosecuting Attorney Amanda L. Oesch has been appointed to serve as an associate judge for the 33rd Judicial Circuit. On Friday, April 12, Gov. Mike Parson announced judicial appointments to the 21st, 22nd,... -

-

Local News 4/12/24Taxiway D bidding to start next week; regional airport sees success over solar eclipse1Airport manager Katrina Amos informed the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport Advisory Board that Taxiway D will be out to bid next week and gave an overview of the solar eclipse’s impact on the airport at the Thursday, April 11, meeting...

Local News 4/12/24Taxiway D bidding to start next week; regional airport sees success over solar eclipse1Airport manager Katrina Amos informed the Cape Girardeau Regional Airport Advisory Board that Taxiway D will be out to bid next week and gave an overview of the solar eclipse’s impact on the airport at the Thursday, April 11, meeting... -

-

Local News 4/12/24Did You Know? Dexter K-9 shooting latest of several cop/dog controversies in Southeast Missouri6A former Dexter K-9 officer was charged last week with alleged felony animal abuse and neglect, which investigators say resulted in the death of the department’s active drug dog Apollo and the serious illness of another retired drug dog Knox...

Local News 4/12/24Did You Know? Dexter K-9 shooting latest of several cop/dog controversies in Southeast Missouri6A former Dexter K-9 officer was charged last week with alleged felony animal abuse and neglect, which investigators say resulted in the death of the department’s active drug dog Apollo and the serious illness of another retired drug dog Knox... -

Local News 4/12/24United Way invites community members to 'Get on the Bus'1“(Not-for-profit organizations) depend on volunteers. We have very limited budgets, and none of us could do our work without the devoted volunteers,” explained Elizabeth Shelton, executive director of United Way of Southeast Missouri...

Local News 4/12/24United Way invites community members to 'Get on the Bus'1“(Not-for-profit organizations) depend on volunteers. We have very limited budgets, and none of us could do our work without the devoted volunteers,” explained Elizabeth Shelton, executive director of United Way of Southeast Missouri... -

-

Most read 4/11/24Cape Girardeau woman accused of biting man for second time3Police arrived to a domestic disturbance call Tuesday, April 9, to find a man bleeding with a tennis ball-sized bite wound to his inner forearm. It allegedly wasn’t the first time. Colleen Ann Lewis, 53, was charged with third-degree assault. ...

Most read 4/11/24Cape Girardeau woman accused of biting man for second time3Police arrived to a domestic disturbance call Tuesday, April 9, to find a man bleeding with a tennis ball-sized bite wound to his inner forearm. It allegedly wasn’t the first time. Colleen Ann Lewis, 53, was charged with third-degree assault. ... -

-

-

Most read 4/9/24Jackson man held for alleged rapeScott Christy, 56, of Jackson was charged Saturday, April 6, with first-degree rape or attempted rape and third-degree assault. Police say the alleged victim called 911 and whispered her street address over the phone, then began screaming before the...

Most read 4/9/24Jackson man held for alleged rapeScott Christy, 56, of Jackson was charged Saturday, April 6, with first-degree rape or attempted rape and third-degree assault. Police say the alleged victim called 911 and whispered her street address over the phone, then began screaming before the...