Pavement Ends

James Baughn was the webmaster of seMissourian.com and its sister newspapers for 20 years. On the side, he maintained even more sites, including Bridgehunter.com, LandmarkHunter.com, TheCapeRock.com, and Humorix. Baughn passed away in 2020 while doing one of the things he loved most: hiking in Southeast Missouri. Here is an archive of his writing about hiking and nature in our area.

More than you wanted to know about Bird's Point (Part 2)

Posted Thursday, May 5, 2011, at 3:43 PM

They wanted to blow up what?

That was my first reaction when I heard about the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' plan to intentionally breach the levee at Bird's Point and send water into the New Madrid Floodway.

It sure seemed like a crazy, MacGyver-like plan. And yet, as I soon learned, this wasn't a spur-of-the-moment scheme. The plan had been on the books since 1928. And it had already been done once.

I had never noticed it before, but many maps of Mississippi County do show, in large letters, the "New Madrid Floodway."

Topographic map from 1956

Topographic map from 1956Surrounded on three sides by the Mississippi River, it's clear that Mississippi County is appropriately named. The Big Muddy has been a key part of the area's history, for good and bad. The river attracted early settlers by offering fertile farmland and access to steamboat trade. But the river has also been an enemy, periodically joining forces with the Ohio River to unleash widespread flooding.

The current flooding situation is terrifying, but yet it is only the latest in a long line of disasters stretching back to the earliest records of pioneers. Bird's Point, located opposite the mouth of the Ohio, has been ground zero for these floods. The area could be a nominee for Flood Capitol of the United States.

From the book "History of Mississippi County Missouri: Beginning through 1972" by Betty F. Powell, it's possible to put together a list of some of the floods in Mississippi County: 1815, 1844, 1858, 1882, 1892, 1897, 1905, 1912, 1913, 1927, 1937, 1945, and 1950. Since that book was published we can add more years: 1993, 1995, 2008, and now 2011.

The Floodway project dates to the Great Flood of 1927 in which half a million people were to forced to flee along the lower Mississippi. As a result, Congress ordered the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to develop a new plan for flood control that would prevent a repeat of the 1927 calamity.

It didn't take long for two different options to be discussed. The first, more expensive, concept involved building reservoirs and diversion channels to hold and distribute the excess water during floods. For example, Gen. John R. Fordyce wanted to build a system of canals and dams, including a hydroelectric dam at Thebes, Illinois. During floods, water could be diverted along a spillway that would run southwest from Cape Girardeau into the St. Francis River.

On the other hand, the Corps of Engineers favored a less expensive plan that didn't require dams and reservoirs. Their vision included floodways, designated areas where water would overflow during extreme floods, helping to reduce river stages elsewhere and take pressure away from other levees.

Maj. Gen. Edgar Jadwin, the chief of engineers and the man put in charge of developing the plan, presented his proposal to President Coolidge in December 1927. The Jadwin Plan, as it soon became known, included the Bird's Point-New Madrid Floodway plan.

Story from the Southeast Missourian, Dec. 8, 1927

The idea was to build a "setback levee" away from the river between Bird's Point and New Madrid. During a catastrophic flood, water would be allowed to spill over the river levee, filling over 130,000 acres (200 square miles) between the setback and river levees. This would spare Cairo, Illinois, from flooding.

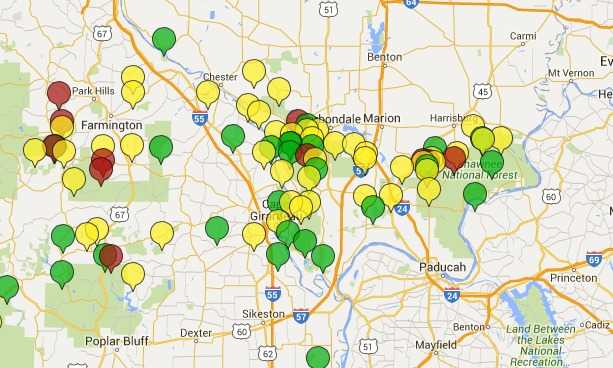

This interactive Google map shows the modern-day location of the floodway. The blue line is the setback levee, while the red line is the mainline levee.

Judging from Southeast Missourian news clippings, it was clear that the plan was controversial from the beginning. Illinois officials and Cairo residents favored it, while Missouri officials and Mississippi County residents opposed it.

U.S. Representative Dewey J. Short called the floodway "a waste of money." He stated, "The project is simply an emergency one and does nothing but ruin a lot of land over which the water flows at high river stage."

The Southeast Missourian asked Otto Kochtitzky, the engineer behind the Little River Drainage District, to comment on the Jadwin Plan. He wrote a negative report, leading the newspaper to conclude in 1930, "Since all of the benefits are intended for one city in an adjoining state and since Mississippi County cannot under any circumstances be benefited in the least, and since no one has ventured to say what extend the damage will go, Mr. Kochtitzky's article shows that the government should at least buy at full value all of the lands in the floodway, because after the first flood sweeps over the area the earning power will be permanently destroyed."

A map of the proposed floodway, prepared by Otto Kochtitzky

Another local engineer, Lucius T. Berthe of Charleston, was an outspoken critic who testified against the plan in Congress and at various engineering societies. He argued that a previous flood in 1913 provided a perfect "laboratory demonstration" of how the floodway plan would -- or wouldn't -- work. During that flood, a levee failed south of Cairo, sending water over a huge part of Mississippi County. This created a precursor to the New Madrid Floodway. The river stage at Cairo only dropped three feet, not the six feet difference that the Jadwin Plan predicted the floodway would provide.

Despite the vocal opposition, the Corps of Engineers proceeded with the plan, constructing the setback levee in 1929-31. The government could not afford to buy all of the affected land outright, so they instead filed condemnation proceedings to obtain "flowage rights" across the land. This began in early 1931, but it took years -- even decades -- of court wrangling to finally gather the easements for 678 tracts of land.

The newspaper archives are filled with stories about the numerous lawsuits over flowage rights. Dollar amounts of the settlements weren't usually revealed, but one article mentions that the government paid $17,921 for the flowage rights on 1,033 acres. That equals about $17.35 per acre.

In 1936, a government official claimed that it might be a long time, possibly decades, before the floodway would need to be activated.

That bold prediction, as we'll see in the next installment of this blog, would be put to the test the following winter as the Ohio River quickly filled to capacity.

Footnote

I've had a couple people ask about the proper spelling of Bird's Point and whether it has an apostrophe or not. Historically, the name was usually spelled with the apostrophe, although some maps and sources spell it Birds Point or Bird Point. This makes sense: the town was named for Abraham Bird, not a bunch of winged creatures, and so the possessive form is the most logical.

In 1893, the name of the post office was changed to Bird Point. This was during a period when the federal government was trying to "simplify" placenames. The end result was to create more confusion as most residents continued to use the older, longer spelling. Glen Allen vs. Glenallen, Burfordsville vs. Burfordville, and Gray's Ridge vs. Grayridge are some other examples of the government meddling with the spelling of placenames.

In modern times, the name is typically spelled Birds Point. That's the style used by the Southeast Missourian and the Corps of Engineers. However, I've seen plenty of sources that still use the older form. Newspaper stories from the 1920s and 1930s use both forms interchangeably. Since this blog is dealing mostly with the history of the place -- when it was most commonly spelled Bird's Point -- that's the style that I'm using.

Respond to this blog

Posting a comment requires a subscription.