Pavement Ends

James Baughn was the webmaster of seMissourian.com and its sister newspapers for 20 years. On the side, he maintained even more sites, including Bridgehunter.com, LandmarkHunter.com, TheCapeRock.com, and Humorix. Baughn passed away in 2020 while doing one of the things he loved most: hiking in Southeast Missouri. Here is an archive of his writing about hiking and nature in our area.

More than you ever wanted to know about the old Cape bridge

Posted Tuesday, July 17, 2007, at 12:58 PM

The purpose of this blog is to seek out quirky, obscure places in the region. It's not very often, though, that I get to explore a brand new place that just opened to the public. Such is the case with the Cape bridge overlook project.

It's been three years since the Cape Girardeau Bridge was demolished. The last remaining vestiges of the bridge, including the west end and the decorative overhead arch, have been incorporated into a new park and overlook.

The park is a fine addition to the Cape riverfront and complements the nearly-finished River Campus. However, it's somewhat disappointing that the park doesn't do more to commemorate the old bridge. In particular, it doesn't preserve a single piece of steel, even though the bridge was primarily a metal, not concrete, structure.

I'm surprised that some enterprising student at the university didn't try to salvage some of the steel girders to produce a modern art sculpture for the River Campus grounds. Or that the city didn't snag a few artifacts -- pieces of guardrail, girders, even some rivets -- to include with the park. (After the demolition, I found several rivets and other pieces of metal scattered next to Aquamsi Street.)

I'm also surprised that some of the original asphalt, with the centerline, wasn't preserved. That would have been an interesting sight for people driving down Morgan Oak Street -- an Evil Knievel centerline to nowhere. Instead, the old bridge approach is now covered with boring paving stones.

The site in 2003, just after the bridge was closed to traffic.

It's gratifying that a small portion of the bridge has been preserved, since it appeared at one time that the entire thing was going to be bulldozed. However, the bridge played a small, but notable, role in civil engineering and more could have been done to capitalize on its history.

Our part in civil engineering history

The preserved plaque lists the bridge's builders.

In 1916, Gustav Lindenthal constructed a railroad bridge at Sciotoville, Ohio, using the same design -- a "continuous through truss" -- that would be employed a decade later at Cape. It was a daring, controversial design that was met with skepticism when Lindenthal first proposed it.

Prominent engineer J.A.L. Waddell had harsh words for continuous truss bridges in his book "Bridge Engineering", written just before construction started on the Sciotoville Bridge. He wrote:

Considerable attention has been given by writers on the subject of bridges to continuous girders, the result being simply a great waste of printer's ink. Few American engineers will countenance the building of continuous girder bridges, except for swing spans. The unanswerable objection to the use of structure of that type is that the correctness of the stresses, found by a most elaborate system of calculations, is dependent upon the exactness of the elevations of the bearings on the piers. The least variation of these from correctness will upset completely every stress in all of the trusses that rest on the pier where the variation exists, to say nothing of how it will affect the stresses in the trusses of the other spans.

Waddell then adds,

It is proper to state, though, that not all American bridge engineers agree with the author in his drastic condemnation of continuous spans; for one of the most prominent of them, Gustav Lindenthal, Esq., C.E., has lately proposed a structure of that type for a crossing of the Ohio River at Sciotoville... The conditions at that crossing, however, are exceedingly favorable for continuous spans, because there is a good solid rock foundation from end to end...

After Lindenthal successfully completed his bridge, the engineering community took notice. He quickly won over the skeptics.

Missouri, as the Show-Me State, has a reputation of adopting ideas only after they have been successfully demonstrated by other states. That's what happened here: Missouri engineers were shown the potential of the continuous design, and by 1930 three such bridges were built over the Mississippi River -- at Quincy (1928), Chain of Rocks in St. Louis (1929), and, yes, at Cape Girardeau (1927).

The Quincy and Chain of Rocks bridges have a different appearance, but the main spans on the old Cape bridge were a carbon copy of the Lindenthal design, except somewhat shorter. Both were "riveted, 20-panel, subdivided-Warren continuous through trusses."

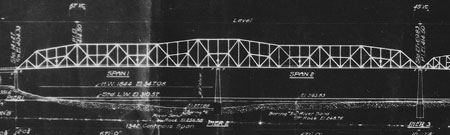

This portion of the Cape bridge's blueprints shows the main spans. Image downloaded from the Historic American Engineering Record.

Indeed, the Cape Giradeau Bridge was one of the first anywhere to employ the Lindenthal design. What had been a controversial piece of engineering soon found its way to our corner of the world.

Waddell did have a good point, however. During the main phase of the bridge's demolition in Sept. 2004, the wrecking crew attempted to implode the first span, but they also caused the immediate collapse of two other spans. I suspect that the explosives caused the center pier to shift slightly, sending the rest of the bridge out of whack -- just as Waddell warned against. Thankfully, the incident had no serious consequences, but did provide one of the most memorable scenes in city history.

Respond to this blog

Posting a comment requires a subscription.